INDEX

1. SIENA - MUSEUMS AND PALAZZI

- State Archives

2. SIENA - CHURCHES

3. PLACES WITHIN HALF AN HOUR OF BARONTOLI

6. SIENESE PAINTERS

7. SAINTS IN ART

ARCHIVIO DI STATO (SIENA STATE ARCHIVES)

Palazzo Piccolomini

A little visited but fascinating display of painted file covers (“Biccherne”) from Siena’s 13th-17th city account books.

Open Monday to Saturday. Visitors are let in at 0930; 1030; and 1130. Free.

The 15th century Palazzo Piccolomini is on the Banchi di Sotto, on the corner with the via Rinaldini. The Piccolomini crest of crescent moons is everywhere; even the rings on the outside of the palazzo for tying up horses are moon shaped. Two papal crowns on the façade recall the two Piccolomini popes. The building now houses various official institutions, including the Siena state archives from the earliest times to the present day. Cross the courtyard and enter the door on the far left marked ‘Archivio di Stato’, or take the lift through the door to the left of the stairs. Up several flights of stairs, almost at the top, you will come to a big wooden door that looks closed but usually is not. Enter and say that you are there ‘per visitare il museo’. When the time comes, you will be let into a set of rooms with the ‘biccherne’ – the decorated wooden covers of the files in which early Sienese governments kept their records. The collection has just been rearranged in display cabinets with excellent explanatory notes in English and Italian (although the individual captions are unfortunately still monoglot).

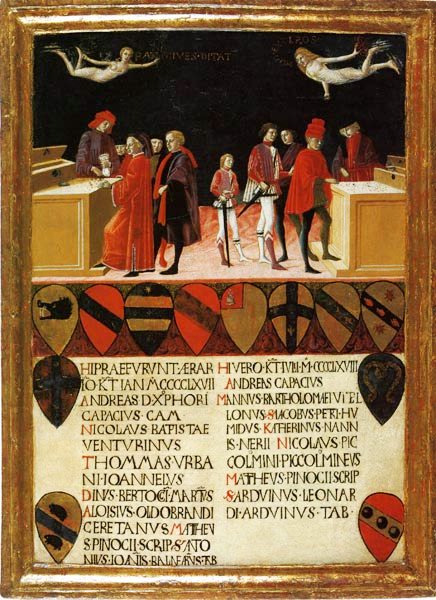

The covers were decorated by many of the best artists of the day and are fascinating because they show - at a time when almost all painting was religious – scenes from contemporary life and episodes from the history of the city. The earliest dates back to 1258. As time went on, they became grander and less utilitarian, and the later ones are frankly wall-paintings rather than file-covers.

The oldest ones concentrate on the life of the officials of the city; No. 5, for instance, shows four officials apparently anxiously discussing a problem. The later ones tend to show the big events of Sienese history - battles, sieges etc.; and allegorical and religious scenes – the Virgin being asked to protect Siena, and at No. 35 a representation of peace (lots of taxes coming into the city coffers) and war (citizens wearing their swords and no money). The views of Siena make clear that it was once a city of many towers, like San Gimignano.

No. 5: Finances in time of peace and war.

Other interesting ones include:

16. A symbolic depiction of the ‘Good Government of Siena’ with a magistrate on a throne and the wolf suckling Romulus and Remus at his feet, painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (who of course was also responsible for the frescoes of good government in the Palazzo Pubblico);

19. The symbolic ‘Government reining in the citizens’;

25. St Jerome removing the thorn from the lion’s paw, by Giovanni di Paolo;

32. A large and magnificent biccherna showing the coronation of Pope Pius II, Siena’s own Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (whose life is depicted in the frescoes in the Piccolomini chapel in the Duomo). Painted by Il Vecchietta.

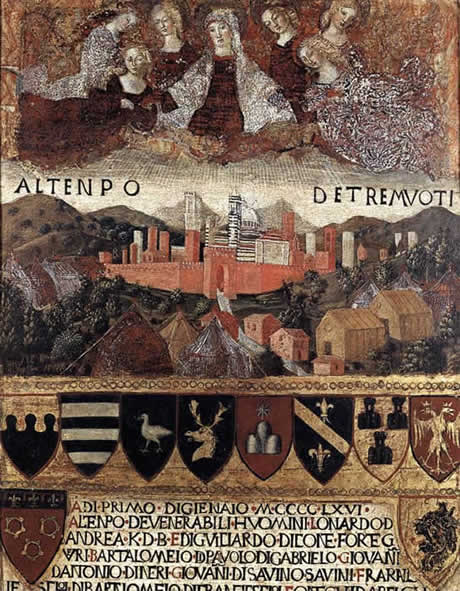

34. The virgin protecting Siena in time of earthquake, by Francesco di Giorgio Martini.

37. The wedding of two young nobles.

38. Another ‘Good Government’.

39. The surrender of Colle Val d’Elsa.

40. The Virgin commending Siena to Jesus, with the city perched rather precariously on stilts. Siena considered the Virgin to be one of its main patrons, from the time of the battle of Monteaperti onwards, and successfully approached her on a number of occasions to save the city from impending disasters.

46. Arrival of an Embassy in Siena.

49. The victory of Camollia in 1526, when the Sienese drove away papal and Florentine forces encamped outside the Porta Camollia.

Note the many towers of Siena.

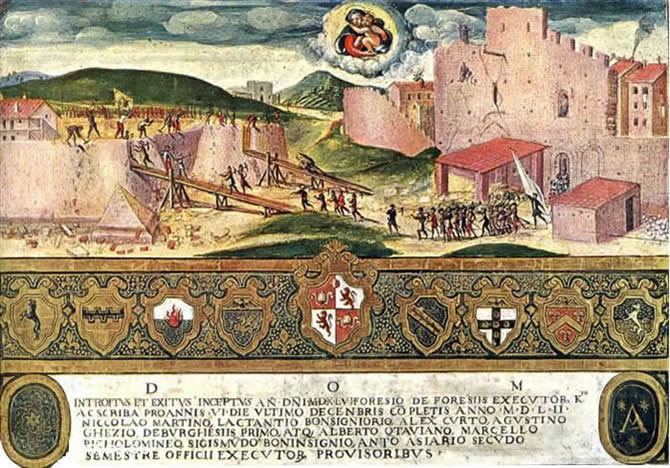

51. Naval victory in the Pelopponese against the Turks.

57. and 58. Two versions of the famous demolition by the Sienese of the fortress built by the Spaniards when they controlled Siena in the 1550s. The Spaniards had constructed the fortress to defend the city against the French (and doubtless also to subdue the citizens of Siena as well). They had infuriated the Sienese by insisting that they provide both the labour and the finance. The Sienese reacted by rebelling and joining forces with the French to drive out the Spaniards. When the French Government representative subsequently entered the city, he took formal possession of the fortress and summoned the Siena city dignatories to hand it over to them. They arrived in a procession with a large number of citizens armed with pickaxes who promptly set about razing the fortress to the ground.

63. The peace treaty of Cateau-Cambrensis and the embrace of Henry II of France and Philip II of Spain. The historically busy 1550s had seen a long struggle between the French and Spaniards for control of Siena, finally ending in 1559 when the two sides signed a peace treaty under which all Spanish rights to Siena passed to France. Thereafter, France merged Siena with the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, finally ending all semblance of Sienese independence.

64. The Tuscan Grand Duke, Cosimo di Medici, entering Siena to take possession of his new dominion.

In the neighbouring rooms and corridors, showcases display some of the more historically interesting and/or highly decorated of the documents preserved in the archives.

1994; revised 2005.