INDEX

1. SIENA - MUSEUMS AND PALAZZI

2. SIENA - CHURCHES

3. PLACES WITHIN HALF AN HOUR OF BARONTOLI

ASCIANO

A town in the middle of the dramatic Crete landscape with an excellent small museum.

Asciano is – and probably has been since Etruscan times – the ancient market town of the Creti area, the grey clay hills across which Guidoriccio da Fogliano rides in the famous fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. Whichever way the town is approached, the landscape is spectacular, the bare hills interrupted only by chasms of erosion and the occasional line of cypress trees along the horizon.

Asciano has one long main street, the Corso Matteotti. At the top end there is the main church, the Collegiata or Basilica di Sant’ Agata, up a broad flight of steps. It is on the hinge of Romanesque and Gothic, and is built entirely of travertine marble. There is nothing particularly special about it; it is just a very attractive church, both outside and in (look particularly at the inside of the dome). There is one good fresco, on the right wall, of the Madonna and Child with St Michael the Archangel, attributed to Girolamo del Pacchia (c.1477-after 1533), a contemporary of Sodoma.

Sant' Agata (the Collegiata)

Just beyond the Collegiata, there is a Carabinieri station which is an excellent example of the architecture of the Mussolini period.

Halfway down the main street there is a red-brick clocktower, the Torre Civica, medieval in origin but much restored. The road beside the clock-tower, via Cassioli, leads down to a small open space, the Piazza del Grano, with an attractive 15th century travertine fountain. Back in the main street, opposite the Torre Civico, there is a chemist’s shop. This building, which like so many in Tuscany has Roman foundations, secretes a Roman mosaic, much pictured on posters. The chemist will show it to visitors on request.

Further down the main street, just beyond the church of San Agostino at No. 122, an ancient palazzo, the Palazzo Corboli, has been transformed into one of the best small museums in Tuscany, taking in the collections from two previous museums (of Sacred Art and Archaeology) which were both boringly laid out and hardly ever open. This Museum of Sacred Art and Archaeology is open every day except Monday from 1000-1300 and 1500-1900 (1030-1300 and 1500-1730 from November to March). It has quite good English captions.

The ground floor has a room devoted to the history of the palazzo, fascinating as it shows how this ancient building (it dates from the early 1200s), like so many in Tuscany, was restructured over the years to suit the needs of subsequent generations without ever losing its essential character. The room also contains the old cess-pit of the palazzo and a show-case of the detritus found within it (old potsherds etc.).

The first floor has a maze of small rooms, including some with part of their original late 13th century frescoes, giving a good idea of how the walls of mediaeval palazzi were decorated. The best is the so-called Sala di Aristotele (Aristotle), covered with panels painted to look like marcle. It takes its name from one of the roundels on the wall depicting Aristotle with his name on a scroll beneath. The other roundels depict Virtues (Prudence, Justice, Strength and Temperance) and various mythological or biblical figures. In a further room, there is a particularly good ceiling with frescoed panels of the four seasons – Winter is unusually represented by a man holding a snow-ball.

Medieval frescoed room

Above all, however, this floor contains a small selection of mainly exquisite works of art. The chef d’oeuvre of the collection, a spirited tryptich by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c.1290-1548) of St Michael the Archangel (a favourite Asciano subject, it seems) slaying a colourful multi-headed dragon. St Michael is flanked by St Bartholomew on the left and St Benedict on the right, both with marvellously expressive faces – note particularly the wise old face of St Benedict. Above there is an exquisite Virgin and Child, reminiscent of the one by the same artist in the Oratorio St Bernardino in Siena (qv).

St George slaying the dragon (detail) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti

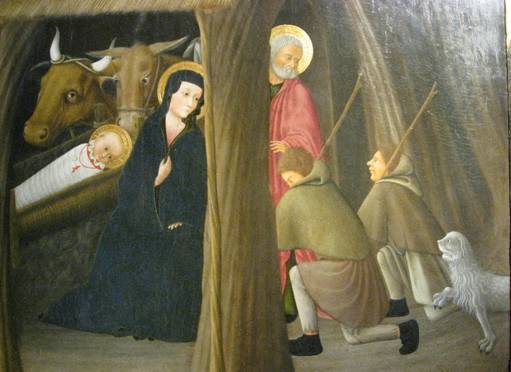

Along to the right, after another frescoed room, there are further paintings, including a good tryptich by Matteo di Giovanni (150 or so years after Lorenzetti) with the Virgin and Child flanked by Saints James and Augustine on the left and Saints Bernardino (instantly recognisable as usual) and Margaret on the right. The strange object that St Margaret holds in her hand is a miniature dragon; according to her legend, one of her many tortures was to be swallowed by a dragon that then burst asunder. Also in this room there is a striking tryptich of the Nativity by Pietro di Giovanni d’Ambrogio (1409/10-1448), an artist from whom very few works have come down to us. While within the conventions of the period, it manages to have a certain rural authenticity. The shepherds are particularly good, looking like real peasants even though they are accompanied by an unlikely lion-like pet. And note the excellent owl – the artist obviously liked animals. The saints on either side are Augustine on the left with a book, as befits a doctor of the church; and Galgano on the right holding his sword in the stone.

Detail of Pietro di Giovanni d’Ambrogio’s Nativity triptych

In the next room of paintings there is a rather confused Coronation of the Virgin opposite by Giovanni di Paolo has rather better side-panels of Saints by Matteo di Giovanni.

We recommend that you pass rapidly through the second floor which has a number of undistinguished later works and the unimpressive first part of the archaeological collection. One room, however, has been given over to a painting of the Birth of the Virgin which may have somewhat wooden faces but is in the best tradition of Sienese decorative art, beautifully composed and with wonderful embroidered robes. The attribution has been much argued over but it is now considered to be by the 15th century Maestro dell’Osservanza, so-called because nobody knows his name and his best painting is in the church in Siena of that name (although the Asciano museum now claims that their Birth of the Virgin is his chef d’oeuvre). The Virgin is said to have been born to an elderly couple, anna and Joaquim, who thought they were well past child-bearing and her birth is almost always represented in the same way in Sienese painting. The mother lies recovering on a bed to the right; mid-wives wash the newly born baby in the centre, and Joaquim sits outside on the left.

The best of the archaeological stuff is on the third floor and consists largely of 4th century BC Etruscan objects found in a nearby Etruscan burial site, including a lot of rather plain urns for the ashes of the dead. There are a couple of quite good Greek-style painted vases and a case of interesting bronze objects, including mirrors and a strainer, testifying to the sophistication of Etruscan society, but nothing of major interest.

There is another museum, the Museo Cassioli, devoted to the paintings of Amos Cassioli, a 19th century artist from Asciano best known for the frescoes in the Sala della Risorgimento in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, of little interest to most visitors.

2004 and 2015