10. MICHAEL AND FLORENCE AND FAMILY, 1946-1977

After the war, Florence and Michael settled into family life in London. Michael was head-hunted by a small venture finance company, Industrial Finance and Investment Company, of which he eventually became Chief Executive. After the birth of Caelia in 1946, Flavia was born in 1949. As Michael’s salary rose, the family could afford resident domestic help, which was still common in those days among the middle classes. When Caelia was born, a trained Nanny was engaged, Olive Winter, who remained with the family for six years. After she left, Spanish au pairs looked after the children. They became long-term friends, inviting the Lamberts to stay with them in Spain. Florence and Michael also employed a series of young girls to cook and clean. They came through the Catholic Church from impoverished regions in Southern Italy, then still extremely primitive. Some of the girls had never seen water coming out of a tap before, let alone hot water, and one thought it was the devil. None stayed very long; having got into England they moved quickly on to become hospital cleaners, for whom the hours were better (resident domestic servants were on call for most of the day and normally had only a couple of afternoons off a week). Then Florence and Michael employed for many years the faithful and much-loved Elisabet, a middle-aged German who acted as their cook and housekeeper. She stayed with them until her retirement in the 1960s.

There are relatively few letters from this period, as Michael no longer travelled as much. Michael and Florence took a number of holidays abroad, without the children, as it was rare in those days for middle class children to be taken on holiday overseas with their parents. Instead, they were sent off on their own holidays with their Nanny at an English sea-side resort.

Rationing continued until the early 1950s. The members of the Lambert family living in London were lucky because they were sent regular food parcels from the farm in Devon, and also from America when George Lambert senior went there on a visit.

Letter 10.1. Jane Macaskie at 27 Kensington Square to Jane Barran in Jerusalem, 8 My 1946 … Florence produced an 8 ½ lb daughter in 3 hours flat yesterday, during much of which she was oblivious. She told me this morning what bliss it is being in one’s own house after doing this kind of thing in hospital and being ordered around from morning to night. … Your niece is very round and fat with long almost black hair growing right down low all round the face like all my family. … She seems very good and Florence and Michael are very pleased with her. She is to be Celia Anne Georgiana. … Georgiana is not as you might think after her delightful and noble grandfather, though I told Michael I hoped he would have the sense to pretend it was, but after the beautiful Duchess of the face without a frown¹. … ¹Georgiana, née Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire (1757-1806), famed for her beauty, her political campaigning on behalf of the Whigs (antecedents of the Liberals) and her scandalous love-life.

Florence with Sophia and Caelia, c.1947

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.2. Margaret Lambert at 57 Apsley House, St John’s Wood N.W.8, to her father George Lambert senior, 14 January 1948

My dear Daddy, I came in tired and depressed this evening after a day of exasperation with the Foreign Office files, to find a huge, heavy American parcel waiting for me. Unpacking it reminded me very much of the thrill we used to get out of our Christmas stockings as children. I unwrapped one thing after another that is practically if not quite unobtainable here – rice, and sultanas, dried fruits, nuts and oil, even currants. I cannot thank you enough and only hope you have not depleted yourselves to send it to me. … -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As a young man, Michael had harboured ambitions of entering politics. He did not do so, but he used occasionally to help his brother in Devon during election campaigns.

Letter 10.3. Michael Lambert at Spreyton, Devon to Florence Lambert at 2 Aubrey Road, 21.2.1950

Darling Heart, George very much wants me to go round some of his polling stations on Thursday. That being so, I shall be returning on Friday. I hope you do not mind too much. I had a very good little meeting at Yeoford last night and everyone seemed quite pleased. They tell me I explain the intricacies of economics with great clarity. Your experience is, I believe, the contrary [Florence was notoriously innumerate]. Funny, isn’t it? I gave them some pretty hard stuff, but they seemed to lap it up. There is a crocus out here, too. All my love, Mickie. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE CORONATION, 2 JUNE 1953

As a peer, Viscount Lambert had a right to attend the coronation, and he had (as an M.P.) attended the three previous coronations – those of Edward VII, George V and George VI. He decided, however, that he was too old and infirm to attend that of Queen Elizabeth II. But he did manage to get prized places for Michael and Florence and their two elder children (aged 10 and 7) on the stands that had been set up along the route of the coronation procession from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey. The family had to be in the stands very early in the morning and had slept the night before at the nearby house of Michael’s parents on Millbank. It was a cold and drizzly day. This is Florence’s thank-you letter to her father-in-law.

Letter 10.4. Florence Lambert in London to Viscount Lambert in Devon, 8 June 1953.

Dear Ba, I feel I must write and thank you for making it possible for us to see the Coronation. We had a superb view and it was a truly magnificent procession. Being so near the Abbey we saw the arrival of the Queen as well as the return procession and our hours of waiting were enlivened by the arrival of all sorts and conditions of person from Peers in their robes to boy scouts. It was very cold but the children did not seem to mind. Caelia ate nearly the whole time and Sophia read. They were very thrilled and will I think always remember this great occasion. I am sorry you and Gang-I could not have been in the Abbey as that must have been lovely too, although probably not very different from your last two Coronations. We thought of you a lot. With love and many thanks from us all, Florence. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Among the most glittering of the celebrations at the time of the Coronation was a ball given by the officers of the Brigade of Guards for the new young Queen at Hampton Court Palace on 29 May. John Roberts, the husband of Florence’s sister Nicola, was an officer in the Welsh Guards and invited Florence and Michael to the ball. The occasion was all the more impressive as Britain was only just emerging from the post-war austerity. Florence wrote a gushing description to her mother-in-law in Devon.

Letter 10.5. Florence Lambert at 2 Aubrey Road, London W.8, to Viscount Lambert in Devon, 8 June 1953

Dear Gang-I, I thought you might like to hear about our big night out with the Queen. We began with dinner here to which John and Nicola came and we had turtle soup, Dover soles with mayonnaise and fruit salad. Then we left in a car kindly lent by Mrs Killery [a cousin by marriage] wearing all our best clothes and long kid gloves. I bought a new gold kid evening bag mounted with pearls and borrowed a very beautiful gold and aquamarine bracelet from my mama. My frock was not very exciting, but it fits beautifully and I got a stiff petticoat to hold out the very full skirt. Nicola looked charming in a very full-skirted pink and deep blue tulle. Michael as usual looked very elegant in his tails. Off we drove and for the last two or three miles the woods were lined with people who cheered us and begged us to turn on the light inside the car so that they could get a better view. We were too shy to do this. We drove in the main gate and up to the great Tudor clock gate with that very old clock, the turreted battlements and the moat, which is now grassed over. The whole front was floodlit and it was the most ravishing sight to see this great pink brick palace against the clear evening sky. It was still dusk and the sky was a delicate duck-egg colour. We went in through the clock gate under the arch flanked by Yeomen in their ruffs and NCOs of the Brigade of Guards in their smart walking-out dress with decorations. These took our tickets and we went through the inner Courtyard and up the grand staircase. All the staterooms were open and all the chandeliers lit, the walls hung with tapestries and everywhere the most beautifully arranged flowers. The Fountain Court, which is one of Wren’s bits, looked especially lovely. It was floodlit, the fountain playing, with a rank of massed pale blue and pink hydrangeas and geraniums around it, set in a wonderful green lawn and then at the edges the grey of the colonnade. When we walked on the grass in the court and looked up at the lighted windows with elegantly dressed ladies sitting in them and strolling with their escorts in the galleries, it was easy to imagine that the Palace of Hampton Court had come alive again. We arrived at about 9.30 and the Queen was not due until 10, so we strolled about and looked at everything. Finally we came to the Grand Hall, where one of the Guards’ bands played for us to dance. A special parquet floor had been put down over Wesley’s oak beams for us to dance on. The walls of the hall were hung with tapestries, making a lovely background for the scarlet uniforms of the band and the great trophies of flowers, which stood in the corners. The stone tracery of the roof was discreetly floodlit. We danced a little and returned to one of the anterooms just in time to see the Queen and Prince Philip walks through. Michael was so thrilled with the whole thing that he danced again and again with me and we were actually on the floor when the Queen and Prince Philip came in for their first dance. She looked beautiful – like a fairy princess. Her dress was pale pink tulle with a full skirt made up of tier upon tier of little flounces. She wore a wisp of a stole to match, a magnificent diamond and ruby necklace and a very beautiful and delicate tiara. She is so much more lovely than any of the photographs and he is very good-looking and a lively and charming dancer. We saw them often after that dancing with each other and with other people and stopping every now and then to talk with friends. Princess Margaret was in white and she looked tiny and exquisite, but she hasn’t the Queen’s radiant presence, which is so impressive and quite irreproducible in a photograph. In one of the galleries there was a champagne buffet where one merely picked up a bottle and some glasses and helped oneself. I have never seen so much champagne. We sat for a time in the gallery sipping our champagne, talking to people we knew and watching the passers-by. There were some really beautiful frocks and magnificent jewellery. It was tiaras, tiaras all the way and there were a surprising number of beautiful women all looking their best. Supper was served downstairs in a long oak-panelled gallery lit by candles in silver candlesticks on the round tables. It was beautifully done and looked quite lovely. The chairs were gold and with the white napery and the silver and flowers on the tables, you can imagine what a lovely sight it was against the dark oak walls. We had salmon, chicken, peas, asparagus, chestnut soufflé, fruit salad and Baba au Rheum, and lots more champagne. After supper we went and walked in the garden. A fountain at the end of a long walk was floodlit gold. It was fascinating to see the strolling couples silhouetted against the gold. The girls in their long crinoline skirts might have belonged to many past ages. When birds flew across the sky over this golden fountain, their wings turned to gold for a few moments, which made the whole thing more like a fairytale than ever. To get back to more mundane things, I must tell you that Michael and John were among the first to discover yet another champagne bar down in Henry Vic’s cellar. I must also tell you that all the ladies’ lavatories had been specially repainted in shining white paint for the occasion and were manned by charming and helpful females in black with lace aprons ready to switch on buttons at a mere nod of the head. The Duchess of Kent was also there with a bevy of podgy little foreign Princes and Princesses. There was one tall, fair, good-looking one who I think must have been Prince Philip’s niece. The Duchess of Kent looked lovely as usual, and Princess Alexandra will be lovely in a year or two, but she is too heavy and schoolgirl yet. We also saw the Duchess of Gloucester. She is very small and insignificant with a pretty little face and no dress sense. As for the Duke, he gets more Hanoverian-looking every day. About half-past three or four we had breakfast – scrambled eggs, sausages and beer. The Queen didn’t leave until after four. She looked as though she was enjoying herself. It was like a private party, no photographers, no gaping crowds and everyone behaved themselves as I suppose one might have expected, though given the way they behaved back at the garden parties, one was almost surprised. Everything was superbly done in the most lavish possible way, although also in the best possible taste. It was a most lovely and unforgettable evening. We left at about 4.30, taking a last lingering look at Henry Vic’s pink battlements now against a pale morning sky, and drove back to London in the dawn. When we got to Kensington, it was quite light, so we decided to drive round and have a look at the decorations. The streets were nearly empty and we saw them very well. Then we went home and were in bed by 5.30. Grace [Michael’s sister] will have told you about the Coronation and how well we saw it and how the children begged to be allowed to spend another night sleeping on the floor at Milbank. Now I must stop. Lots of love, Florence ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ELECTRICITY COMES TO SPREYTON

Until 1955, Spreyton, like many other rural Devon villages, had no electricity. Houses were lit at night by oil lamps; heating was inefficiently provided by open fires or paraffin heaters; and water heated and food cooked on wood-burning stoves (there was also an evil-smelling paraffin cooker at Coffins). The letter below from Grace Lambert to her maternal uncle describes how the village celebrated the arrival of electricity. The village continued to depend entirely on wells for its water until the mains arrived in 1961.

Letter 10.6. Grace Lambert at Spreyton to her uncle Tom Stavers in Roehampton, 21 April 1955

…We now have electricity, and just can’t imagine how we ever lived without it. It made a wonderful homecoming for Mummy and Daddy, for it was still very cold when they left the warm hotel at Exeter. We had a wonderful inauguration when George [her brother was now the local MP] pressed a button and the village lit up – although, at the time, we were not quite connected. The electricity Board, as a celebration, floodlit the church, which was one of the finest sights I have ever seen – this old church standing out against the moor at the back. It was hardly surprising that the fire brigade, sent for to put out somebody’s car, thought the church was on fire. At the pub, they cooked a 50lb joint of beef, and even the firemen joined in the feasting, so you can see that all had a good time. Now the villagers are busy making use of the different electrical appliances left on approval by the different electricity firms – the bailiff’s wife has hovered her whole house, and I have told Sidney the gardener that, if he didn’t take the chance of getting all his clothes washed in the Hoover washing machine, he must be a fool… Now I suppose the election will be upon us. I can’t say there is much excitement as yet. It will be a grind for George, four meetings a night for three weeks. Still, I suppose he is luckier than some with a small majority. It all seems somehow rather flat now Churchill has gone, for whether one was for him or against, at least he was wonderful value. You must have missed the papers very much at Roehampton [there had been a newspaper strike in London]. Here we have a local one, which is really very good about general news. George and the parish and district councils have been having a spirited slinging match in it recently, about building some bungalows at the end of our drive, where there is no water. … -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SPAIN

In the 1950s, Michael and Florence employed a Spanish au pair girl, Julia Nuňez, to look after their children. She was succeeded after a year by a friend of hers called Maria Jimenez, and then by Maria’s older sister Encarna. As a result, the Lamberts became friends of the Nuňez and Jimenez families and were invited to stay in the house of the Jimenez in the large village of Higuera de la Sierra in Andalucia. Caelia, in particular, formed a lasting attachment to Spain and things Spanish and went several times to stay with the family, which included two children of around her age. Michael already spoke reasonable Spanish, and Florence, who had an enviable gift for languages, also quickly learnt Spanish as a result of her visits there. Florence (2nd left), Michael, Sophia (on Michael’s lap) and Caelia (on the ground, left) with members of the Jimenez family at mountain shrine near Higuera Letter 10.7. Florence Lambert in Higuera de la Sierra, Andalucia, to Jane Macaskie at 27 Kensington Square, 29 August 1954

Dear Mommy, I am writing this in the patio of Maria’s house, surrounded by scented plants and great navy blue bumblebees humming overhead – jasmine, verbena, a palm tree and gorgeous deep blue morning glory; bamboos unknown, flowering shrubs, geraniums, ferns in curious cork flower-pots, roses, begonias etc. A soft breeze is blowing and above there is a deep blue sky, and outside in the street a very, very hot sun. In here it is dappled and the climate is perfect. It is about one o’clock. Lunch will not be until 2.30, and then we sleep until about seven. Then everyone gets up and puts on their best clothes and a posy of jasmine or tuberose in the hair or corsage. The children are washed and brushed and put on starched petticoats and newly whitened sandals and their charming embroidered cotton frocks made in the village. An equally starched little children’s maid takes them down to “the field”, a sort of common with olive trees just outside the village, where the little girls play quiet games and the boys run about and Sophia looks for lizards. The grown-ups walk slowly down the road as far as the field and then back to the village square where there is a café and where the buses arrive. There in the dark we sit and drink manzanilla and eat little pieces of ham and octopus and pommes frites, and watch the town go by. Eventually, at about 9.30, the children reappear and finish up the bits and sip our drinks. Then we all walk slowly back to the house and dine at 10, the children on the patio and us in the house. After dinner, the children play chess or go for little walks with little friends and we sit in wicker armchairs in the street outside the house – the street is a gentle slope with occasional shallow steps and everyone else sits out too under the street lamps and talks far into the night. The children go reluctantly to bed at 12. Now I must stop because the pre-luncheon drinks and ham bits have arrived. Slightly tight and I continue this letter. The children are having their baths which consists of being well scrubbed and dipped in a cold tank in a corner of the patio overgrown with morning glory. They make an awful fuss, especially Sophia and the little boy Manolin. He is sweet, very like Bambi in the Walt Disney film. The children have got very thin and brown, but they look well, especially Caelia who has become very Spanish and is much admired by everyone. All the Mamas tell me how pretty they think her, and they all say as usual that I don’t look at all English. There are two Cambridge undergraduates in the village who stopped for a drink two days ago and liked it so much here that they are staying until Monday to take part (what part I don’t quite know) in the bull-fight tomorrow. Tomorrow and Monday are the two days of fiesta of Sant’ Antonio and, as far as I can gather, promise to be a pretty drunken party. Peaches soaked in wine. It is such fun to be staying in a private house and not to feel like a tourist. All the millions of aunts and uncles and cousins come and meet us and everyone is most kind and sweet. I can now speak Spanish quite fluently and understand almost everything in spite of the local dialect. Yesterday we had a lovely day in the country. Nine people in a hired car, including three children. The countryside is very beautiful, like Umbria and Toscana, only more green and bosky, and in the hills there are orchards of apple, pear, peach, cherry and chestnuts besides the olives and cork trees. We also visited a very impressive cave with stalactites at a sweet little place called Aracena. I am not what the Spaniards call afficionado of caves any more, but it was a very good one and Sophia managed to find some little pieces of stalactite on the ground. There were lovely blue fathomless lakes too, lit underwater by electricity – a dangerous proceeding – one of our party got a shock when she dipped her finger in. We had a lovely open air lunch near a shrine on the top of a mountain where there there was also a spring bubbling up from the hillside which one drank and washed in. Lunch appeared beautifully cooked as if by magic from a minute shack, and by the spring sat a shepherd playing his rustic pipe. This country is far less bogus than France or Italy and it is only in the big hotels that things are put on for the tourists. I am enjoying it very much and feel better than I’ve felt on a holiday for ages. I will now tell you rather back to front about the journey [Sophia and Caelia had gone ahead with Maria and Florence and Michael flew out with Flavia, aged 4]. We started badly by going to London Airport rather than Northolt and only because our plane was delayed did we catch it at all. It was stormy all the way and Flavia, who wouldn’t sit still, began to feel sick after about one and a half hours. However, when I clapped a paper bag over her face like a nose-tag, she was so incensed that she went to sleep instead of being sick. We landed on time, but we had made the mistake of eating the bacon and eggs provided on the plane, and what with singing in the ears [planes were much less efficiently pressurised at that time] and two breakfasts we did not enjoy our lunch. [Illegible] had chosen sole with ecrevisse sauce followed by enormous and rather untender steaks with truffles and cêpes. It was too much, as we had to eat it rather quickly. Flavia was quite good and ate her foie de veau wearing my hat and looking ravishing. The train was quite empty and, except for an interminable wait in the Spanish customs which was hot and crowded, all went well. We dined not very well on the Spanish train and Flavia had some wine and behaved very well. Eventually she fell asleep and slept until we arrived at Burgos. The Spanish train became incredibly full and I had great difficulty keeping the two seats Flavia was asleep on. One woman was very persistent, so I offered her my seat which somewhat shamed her. Then I asked in a loud voice how long she had been travelling and she was forced to admit that it was one hour against our eighteen. Then a nice little Portuguese gentleman gave her his seat. Eveybody else was very friendly and Julia met us on the platform. The hotel in Burgos was very good indeed. … The next morning I met my Waterloo at High Mass in the Cathedral. I had to leave suddenly which was infuriating as never have I been at a more colourful, animated or exciting Mass and the Cathedral is beautiful with its golden gates and carved retablos [alter-pieces] and the choir is very good. However, I wished to be sick etc., and fled to a little stone room just outside the West door. There a French lady came to comfort me and on hearing my trouble said “Ah, comme c’est étrange; mon frère aussi”. He had the only chair and was sitting outside in the sun looking very green. After a bit a gloriously clad Monsignore emerged from a door in the little ante-room and asked me what I wanted. I could only think of the Spanish for Retreat, and he led me into a beautiful Sacristy and sat me on a couple of red velvet cushions, which was the last sort of place I desired. Eventually, I made him understand my need and he led me out into a little courtyard where there was an old granite font which was just the thing. He then produced a French-speaking Monsignore and I asked for the loo, whereupon I was led inside again by numerous Monsignori and Canons all gorgeously apparelled and handed over to a very good-looking young seminarist, who to my horror led me through a door practically onto the altar of one of the side-chapels in the Cathedral, where Mass was just ending, and when I appeared the priest turned round and announced that the next Mass would be in another chapel and everybody got up and swep out. Me and the seminarist were swep with them and at last, after dodging the procession which was going on all over the Cathedral, my guide with a flourish threw open the door of one of the smelliest loos I have had the pleasure of, but it was like heaven and I had some Bronco [lavatory paper] in my pocket. We went back to the hotel and I found that I had a temperature, which by evening had gone up to 101 degrees [Fahrenheit]. However, I took various pills and by next morning it was normal and I ate some lunch and got up for dinner. We managed to get Flavia and Julia off to Madrid in the bus on the Monday and Michael and I stayed until Wednesday and enjoyed Burgos very much. Since then, touch wood, I have been very well. We went straight to Madrid and found Flavia quite dug in and much enamoured of Julia’s very attractive younger brother aged 21. Everyone is so hospitable and we did not get to bed until three on two of the nights we were in Madrid. … Now I must stop. It is Sunday after Mass and wee have just returned from a visit to yet another aunt. The children, all in their best clothes, have been watching the bulls being corralled. This afternoon is the fight. I hope I shall like it. The children seem to. … The bull run passing the house of the Jimenez family (on the left) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Apart from the trips to Spain, the children mainly spent their holidays staying in Spreyton, where they became very involved with the life of the family farm; when there was a sickly or orphan lamb, the children were often given responsibility for feeding it. Until George Lambert senior’s death in 1858, they stayed in his house, Coffins. After his death, Michael’s brother George inherited the estate and took over Coffins. However, he let Michael’s family have the use of Falkedon, a farmhouse on the estate. Caelia was keen on riding and a pony was hired for her use.

Letter 10.8. Caelia Lambert at Coffins, Spreyton, Devon, to Florence Lambert at 2 Aubrey Road, 1 May 1957 (postcard)

Dear Mummy, Sorry I have not written sooner, but I have been very busy. Louise [her first cousin, George’s daughter] and Co. went today. We have just got a new violet-coloured bird. Last night a pig had 16 babies. We have a new cow that gives 6 gallons a day. We went to a point-to-point and met a man who told us which horses would win, and they did. Have you seen the comet? I have seen it twice. We have a new farm labourer called Reg Kingsland. They are building a Dutch barn on the dung-heap, and in the summer they are making all the cowshed into a place like where the cows are milked. We had a pet lamb called Penny. We had to catch the ewe, which we marked with our Easter egg ribbons, to feed Penny. But this morning Penny died. Today I rode Violet [one of the farm cart-horses] back from the field after planting teddies [Devon dialect for potatoes]. Encarna wants to know when we go back. In a year, we are getting 30 new cows. I hope you and all the pets are OK. We are. Caelia. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.9. Michael Lambert in Spreyton to Florence Lambert in Higuera de la Sierra, Andalucia, 5 August 1957

Darling sweetie, No word from you, which I hope means you have had no mishaps. Sophia [who had chosen to go to Devon rather than Spain for her summer holiday that year] is very happy now that Louise has arrived. They found a baby house-martin which has to be fed on thirty flies a day. The two of them spend their time madly searching for flies. They have also been trying to pluck a duck’s head, as the cat would not eat it with the feathers on. With all these animals in their room, they have to keep the window shut. Georgie [Louise’s brother] said he had never smelt such a toe-fug. The last two mornings I was out on the Roman road at Burrington Moor, which was the furthest we got [Michael was tracing Roman roads in Devon, about which he subsequently wrote a paper]. Yesterday I took Georgie with me in the landrover. He was thrilled, as we explored the old aerodrome at Winkleigh. Of course, it rained most of the time, although the rest of England seems to have had wonderful weather. There was the Spreyton flower-show on Saturday. The two girls were furiously trying to win races so as to spend money on cat-food [to feed the farm cats, which otherwise survived on scraps]. Georgie won a race but handed back the money. He and I amuse ourselves by shooting tins off the sundial with an airgun. All my love, Mickie --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.10. Florence Lambert in Higuera de la Sierra, Andalucia, to Grace Lambert in Spreyton, 10 August 1957.

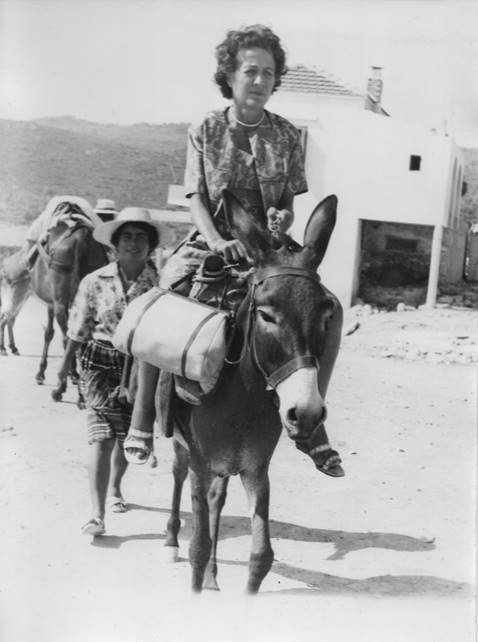

Dearest Grace, How I wish you were here. It is great fun and very restful. Our days are something like this – get up at about 9 and have breakfast in the patio festooned with morning glory and jasmine and other flowers and under a palm tree, while aged peasant women pass too and fro bringing filled water jars [The house had no running water and water was brought in from a well in large earthenware jars] and various produce and our cock crows loudly. He lives in a little shady enclosure under a vine trellis next to the loo [The loo was a stinking earth toilet in a hut in the furthest corner of the patio, well disguised by plants and trellises] and has temporary wives who, after being fattened on the most incredible scraps, including melon rind, are eaten and then another wife is purchased. I don’t quite see the point of him, but he is very colourful and gay. The morning I write letters or read or take a little walk up the village and look at the market – all the shopping is done by the maids – there are three, all very young and sweet – but I like to cast an eagle eye and see that they have not missed anything rich and rare. Encarna is very grateful because she has her hands full keeping her mamma from upsetting the maids and generally directing operations. At about 12.30, I change into my swimsuit and sunbathe on the lilo which I purchased for the purpose. Then I read and sometimes we go to someone’s house for drinks. Lunch is at 2.30. The children go every day about 1 to bathe in someone’s pool – there are several friends who have one – and return very hungry. At about 3.30 we all go to bed for the siesta and I am glad to say that the children sleep too, so I have no qualms about letting Flavia stay up till midnight. At about 6 or 6.30 we arise and have tea in the patio and put our nicest dresses on – the children too – and go to the paseo or evening stroll. The children join up with friends and play until 10, when we go home and dinner is at 10.30. After that, one can go out again visiting, or people come or, as tonight, one sits and reads or writes. Bed about midnight, but sometimes later. Yesterday the children went for a donkey ride into the country. They left about 5, took a picnic tea and came back about sunset which is about 9. They looked enchanting. The donkeys have coloured trappings and each little girl mounts behind a little boy and they go careering along at quite a bat. Caelia said they had some good canters and some of the donkeys were as big as ponies. I was very surprised and relieved that Flavia [aged 7] did not fall off. They came back with the saddlebags full off terrapins, one as large as our tortoise, which they had fished out of some stream…. The least good thing here is the food, as the market is so limited, but the fruit is good and vegetables and fish which comes fresh every day. No one has a fridge, so nothing is kept. [Almost no meat was available, except after a bull-fight, and then it was extremely tough.] … ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Shortly after the aboveletter was written, Florence went off to Portugal, leaving Caelia and Flavia behind in Higuiera. The people mentioned in the letter below are either members of the Jimenez family or from other middle class families who had summer residences in Higuiera.

Letter 10.11. Caelia Lambert (aged 11) at Higuera de la Sierra, to Florence Lambert at the Pension Pinguin, Praia da Rocha, Portugal, 3 September 1957

Dear Mummy,

I am sorry that I have not written sooner but yesterday I had a slight tempretur and I could not go to Santa Marina on horses. Flavia this morning was very naughty because, as yesterday she had a lot of sun, Encarna did not want her to bath, so she started to cry. Then Encarna gave her some medicin which she did not want, so she cryed all morning. We got your first letter on Friday and on Thursday August 29th Clearopatria died [Cleopatra was her one of terrapins – the other was Antony – which she had taken in their aquarium to Spain with her]. On Satday, the parents of that child who died came and took us to a little village which was very poor, and when we got out of the car, all the children came and looked and when we walked throught the streets, everybody came to their door or window and looked at us. … Yestaday Encarna showed us a mother ginypig with two babies. If you take them into a country, do they have to be in croratin? If not Flavia wants one. On Sunday there is going to be a fiesta in a place in the country called the Romeria [actually the word for a festive pilgrimage] and everybody dresses up in flamincas and gose in cars. And I am going with Teresina and all her lot in a bus and Encarna has got me a white flamenca beloning to one of her cousins called Pelar [Pilar] or something. … On Thursday we went out into the country on donkys and we had tea nexted to a herd of cows and there were two bulls that had enormous horns. Then we saw some sort of insect like a bird that eats oil and it clings to your hair and you cannot get it off unless you cut off your hair [unidentified]. Now the hens lay an egg practetctely every day. In the bull-fight for the fiesta of San Antonio, Antonio [Ordoñez, with whose family in Seville Caelia later stayed for a time] took the key part of the ceremonial of the bull-fight. Margarita has a smoke bomb that, if you let it off in a room, sometimes all sorts of poisnes insects fall from the roof and walls and liy dead on the ground. Love, Caelia ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Caelia in Higuera de la Sierra

Caelia went again to spend the summer in Higuera de la Sierra in 1960. She was now aged 13.

Letter 10.12. Michael Lambert in London to his mother Barbara Lambert in Devon, summer/autumn 1960

Dearest Mother, We have just got a letter from Encarna in Spain, and you may be amused to hear what she has to say about Caelia: ‘About Caelia, I do not know how to express myself to let you know the formidable impression she created on everybody. Her pleasing character and good manners have enchanted everyone. I have been able to observe how often men in the street give her the glad eye. Otilia (an aristocratic friend of Encarna’s, very conscious of her noble lineage) told me with a certain reserve that Caelia had created great havoc in the heart of her son Manolin. I have heard some of my friends, married men and grown up, say that she was one of the best-looking girls and with the best figure in the village. As far as I am concerned, I can only say that no one could have given me more welcome and charming company than she with her almost childish fourteen years has given us in the sad time that we are going through.’ [Encarna’s mother had just died] … [last part of letter missing] ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

IRELAND

During the 1960s, Michael’s investment company was involved in financing a sawmill in Northern Ireland for making chipboard, and he made a number of visits to Ireland..

Letter 10.13. Michael Lambert on the Rosslare-Fishguard ferry, to Florence Lambert at the Villa Refugium, Ascona (where she was staying with an old Hungarian friend, Charles Radnotfay), 4 September 1960

Darling Heart, Thanks to the Irish, I have got myself into a proper muddle. I meant to fly back from Dublin on Friday night, but Redmond Cunningham¹ exerted all his powers of Irish persuasion to get me down to Waterford. I was a bit doubtful as it involved getting back at short notice on a Saturday in the holiday season. However, he assured me he could fix it all. In the event, it turned out more difficult than he thought. At the last moment he got me on the Rosslare-Fishguard boat, jam-packed with holiday-makers and no cabins available. I am having to sit up in the lounge next to a screaming baby until 3 a.m. when I get a train to get into Paddington at 11.15 a.m. I can imagine you sitting in the warm evening air with the prospect of a comfortable bed and nothing to do. However, by the time you get this I hope to be back in civilisation. One of the people at Waterford runs a large nursery which I went over this morning. It was an extraordinary sight seeing all the roses not merely in bloom but with hundreds of buds. On Rosary Sunday, which as you know is the first Sunday in October, they pick 2,000 blooms for the churches. I had some fun in a public house this morning. The Mayor of Waterford came in with a Monsignor. As the only heretic in the company present, I saw my opportunity. I engaged the Monsignor in conversation and found he came from London and had a mother from Devon. I quickly made him aware that I was a heretic. ‘I hope you are not black,’ he said. I assured him I was as white as white could be. We had an agreeable conversation. I noticed when we left that the people at the bar treated me with marked respect. I was able to point out to Redmond how we in England do not go in for all this bigotry. As a matter of fact, Ulster is far worse than the South. John Hamilton Stubber² said my face was a study when it was said at our Board Meeting that one of our key fitters could not get a house because of his religion. I really could not see why our efforts to turn an honest penny should be thwarted by the local council. However, being a person of discretion, in the end I instructed the secretary to make a personal call on the secretary of the Rural District Council to ask if could not, in this case, oblige. As I said to the Monsignor, like Agag, I have to walk delicately. At the nursery this morning, I was advised against a thuya for Falkedon, as they do not do too well in a damp climate. Instead, I ordered a cupressus Allumii which has a pleasantly glaucous leaf, grows ten to fifteen feet high and has a pleasing bulbous shape. I think it will look very well at Falkedon. I have at last got back to London. Owing to an accident to the Cork train, the boat was two hours late leaving Ireland, to which the G.W.R. [Great Western Railway] added two more hours getting up to London. All my love, Michael.

¹ Redmond Cunningham (1916-2000). Architect from Waterford. He served in the British Army during the Second World War and was awarded an MC for his exploits during the D-Day landings in Normandy. Also well-known in the racing world. His hospitality was described as “all-embracing and perfectly lethal”.

² John Hamilton-Stubber. A prominent Ulsterman (he was Lord Lieutenant of Tyrone 1979-1986) and timber treatment expert who was on the board of the chipboard company in Ulster financed by Michael Lambert’s firm. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VARIOUS

The Lambert family outside 2 Aubrey Road

Most surviving letters from Flavia in the 1950s and 1960s were written while she was staying abroad. But there are a few from her in the early 1960s to Sophia, who was in Paris. Some were written from London, and some from Falkedon, the farmhouse on the Lambert estate in Devon that Michael’s brother George let Michael and Florence use.

Letter 10.14. Flavia Lambert (aged 11) in London to Sophia Lambert, c/o Mme Hatvany, 44 rue Pierre Guerin, Paris 16me, 27 November 1960

Dear Sophia, I have just got into bed and I’m waiting for my supper. Mummy, John Rickett¹ and Daddy are having a long planting weekend [at Falkedon], but I would of thought it would have been better to plant water lilies; anyhow, I’m sure they have a better chance of survival. But there is no real flood as far as I know. On Saturday I went to a film called “The Spider’s Web”, a novel by Agatha Christie which held one in great suspense and the murderer was the one who one expected the least, and then there was another film called “The Cage of Evil” which was an American gangster film and not very good. Margie came to dinner a few days ago, for she had just come down from Scotland [where she was a lecturer in history at St Andrews University] and was staying a few days in London, before she went to her Exeter house to write her book. The book [which she never finished] is about the history of Europe from 1918-1945. I wouldn’t have thought anyone could bear reading about the history of Europe from 1918-1945, the ideal for me would have been the French Revolution to the end of the Russian Revolution (what date that was I have no Idear), but I suppose when I’m grown up I will enjoy reading books like that. The other thing was that William [her great-uncle William Stavers, brother of Barbara Lambert] had had a stroke and was unconscious. Luckily he had just moved to the nursing home. On Friday, just before I went to school, Daddy told me that William had died on Thursday evening and Gangi was the only one left of seven brothers and sisters. She is doing fine, as far as I know, but I still don’t know if she has been told about Williams death and if so what effect it had on her, but when Mummy comes back on Tuesday I will know. I forgot to tell you what film I went to see today. We went with Julian [her first cousin, Jane Barran’s second son] because we were to lunch with Hane [Sophia’s childish name for their grandmother] and Grandnick [the name his grandchildren gave to Nick Macaskie]. The film was called the Wild Cat. Awken [great-aunt] dropped in as well. Hane told me that Helena [Roberts, first cousin] had had a sort of ammonia (I know the spelling is absolutely haywire), but she is better now and, when I played some games with the Roberts, she was standing in her cot looking quite happy. …

¹ John Rickett, director of Sotheby’s and expert in impressionist and post-impressionist painting. Florence met and became very friendly with him when she worked at Sotheby’s in the 1950s. He was a great fan of Flavia’s when she was a child. He lodged for a time in the top floor of Nick and Jane Macaskie’s house at 27 Kensington Square, and also got to know Jane and David Barran and other members of the family. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.15. Flavia Lambert at Falkedon, Spreyton, Devon to Sophia Lambert (probably in Paris), 8 April 1961(?)

Dear Sophia, … Daddy came down yesterday at about 11 o’clock. I was unfortunately in bed at the time because he was bringing Girl and Eagle [comics] (in the morning I found they hadn’t even arrived), and then he left early in the morning ‘to earn money for his ladies’ as he put it. Auntie Pat and U.G. left Folly (the dog) in our care for the evening, much to my delight and much to Mummy’s disgust. We had a long argument about how wonderful dogs were, Mummy’s argument was how terrible dogs were. It ended with me going to bed. I found some trout in the stream outside the garden and I tried in vain to catch some. It was most irritating; I would dangle the worm in front of their noses, but they took no notice at all. I went for a walk to pick some primroses and on the way back I found the new man (whose name I always forget) [a farmworker employed on the family farm] yelling at the top of his voice at nothing in the orchard. After straining my eyes for a minute, a string of cows appeared from three very large fields away, and they came after a long time, they took no thought of hurrying, in the orchard. I never thought they would answer a call so far away. From the gate, yes; but not that far. … They have started bringing the main [water] down and every time I pass they wink and call me goldy-locks and other such names. Once I passed and they came up to my bicycle and started admiring it: “speedometer”, “lights”, etc., and I must say it is a jolly nice bike. I went down Horsehill at a rate of thirty miles an hour or 45 kilometres. We have no water unless we pump by a hand pump which is jolly hard, believe me it’s hard work. I’ve sampled it. Mummy goes up to Coffins regularly to have baths, she is so fussy or else she must get very dirty. Yesterday she had a go at her sciatica affair. It’s like a long suspender belt with bits of iron in it and when she tried to bend down it stuck into her and when she sat she had to sit bolt upright. Love from your dear Flavia ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Georgie, George Lambert junior (who was later to be tragically killed in a car accident), had his 21st birthday at Coffins, Spreyton, in 1962. Florence Lambert’s novelist cousin, Frank Tuohy, who was staying with the Lamberts in Devon, wrote this tongue-in-cheek account of the rather feudal birthday celebrations for the tenants, estate workers and villagers.

Letter 10.16. Frank Tuohy¹ at Falkedon, Spreyton, Devon, to Sophia Lambert in Paris, 21 August 1962.

My dear Sophia, Your mother asked me to write and tell you about Georgie’s twenty-first birthday for the tenants etc. Also, this may preserve you from losing face at Cook’s by asking for letters and not having any [Frank was living in a time-warp; even in the 1960s Cook’s travel agency no longer acted as a poste restante]. The party was considered to be a great success. Expertly staged by your uncle [Georgie’s father], it became like one of those Pirandellesque plays in which the stage manager plays the principal role. However, the tenants, etc., who all looked rather short and gnarled and brick-red, seemed to enjoy their port and pale ale (mixed) and even got hold of a case of brandy, whisky and campari, not intended for the likes of them, which unfortunately had not been hidden safely enough. The stage manager then blew his top, but his wrath fell largely on the hero of the evening. He, however, had a new silk shirt and was quietly preening himself and inviting people to stroke it (the shirt). The results of the brandy-campari mixture were not in evidence during the party, but the bacchanalia continued in the village and, according to your father, wives were not speaking to their husbands the following day. I had a lot of interesting conversations. I was able to assure people that your father approved of the Common Market, and, when they asked after you fondly, to assure them you were well. They also said that Louise [Georgie’s sister had been a debutante] had lost most of her puppy-fat, which sounded rather revolting (PAL meat for dogs now contains 15% pure deb’s puppy fat). Georgie made a very good speech, although he had to apologise afterwards for forgetting to say thank you for the largest and most expensive-looking of his presents. He also said he hoped they would have as much reverence for him as for his grandfather. There was a pause after this in which one could hear minds boggling. All in all, it was a memorable occasion. …

¹ Francis (Frank) Tuohy (1925-1999) was the son of Jane Macaskie’s cousin Gerald Tuohy and his wife Dodo (see letter...), and therefore a second cousin of Florence. He was a writer who published several novels and books of short stories as well as a biography of Yeats. He never married. Florence and Michael and their family were extremely fond of him and saw a lot of him. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.17. Margaret Lambert at 39 Thornhill Road, London N.1. to her sister Grace Lambert in Exeter, 20 February 1965.

Dearest Gracie, I have just come back from tea at the rabbit hutch [a tiny mews house near Harrods that her brother George was using as his London base], where I saw George and Patsy and the children… Patsy told me three things about Sir Winston’s death and funeral that she had got from Peregrine (who is I think one of the grandchildren) [more probably Churchill’s nephew Peregrine Spencer-Churchill, son of his brother Jack]. The first was that, when they were walking in the procession immediately behind the coffin, they could not hear any of the bands, but only the sound of marching feet, and it was most impressive to walk three miles to the sound of nothing but the steps of a slow march. The second was that Sir Winston’s ginger cat lay on his bed throughout his illness with its head on his hand and would not be parted from him – this went on for nearly a fortnight as apparently Sir Winston was ill for a week before the public announcement. The third thing was that, as they went on the train to Blenheim, there were people not only standing in the stations they went through but also lining the fields on either side of the railway. … After a week of seclusion with the builders, I have actually been out to lunch twice, both times with Norah Smallwoodˡ, with whom Enid went to France. Yesterday she came to see this house and then took us out to lunch at the Antelope, which is a pub near Eton Square, and where we had none of us been for years. It was a great centre for the RAF during the war, so I think it reminded her of her husband Peter to be there with us. Then today she persuaded us to go to lunch at her flat in Vincent Square to meet her very old friends Commander Cohen and his wife. … Norah’s neighbour is a Tory M.P. who has been there for years. He congratulated Harold Wilson [the then Prime Minister] on his memorial speech for Sir Winston. Wilson said he had made a point of learning his speech by heart for a read speech sounds so thin on such an occasion. He then laughed and said “I know all of you think I am awful, but it is such an easy job leading the Tories. Anybody could do that. You just try and lead the Labour Party. We get all the trade unionists, and all the intellectuals, and everybody with a chip on their shoulder. They all join us, and that’s a nice mixed bag to hold together.” When we heard this story, we were all amazed, but decided that Wilson, who is as clever as a bagful of monkeys, evidently knows what he is talking about and perhaps wants to give himself a better “image” as the advertising boys say. … All my love, Margaret

ˡ Norah Smallwood (1909-1984), an old friend of Margie and Enid, joined the publishers Chatto and Windus as a secretary in 1936 and worked her way up to become its chairman and managing director in 1975. Her husband Peter was killed in 1943 flying with the RAF. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One of the people whom Florence worked with in Sotheby’s in the 1950s was their furniture expert Richard Timewell. They remained friends after she left and she and Sophia went to stay in the wonderful house in Tangier to which he retired, Villa Léon l’Africain, becoming a prominent member of the expatriate gay community. (Villa Leon was subsequently purchased by the couturier Yves St Laurent and his partner Pierre Berger.) Richard sent the following letter to Florence when she was in the Middlesex Hospital having treatment for a cyst on her spine (from which she remained incapacitated in her hands for the rest of her life).

Letter 10.18. Richard Timewell at D1 Albany W.1.to Florence Lambert on the Middlesex Hospital, London. 1 June 1965

My dear Florence, I was very sorry to hear last night from Michael that you are a poor spineless creature lying on a bed of anguish. I shall try to come to see you but, as I am about to leave England for two years if not for ever, I am harried and distracted and have to be packed up (the contents, I mean) and put into store. I am going to live two-thirds in New York and one-third in Morocco – not too bad a prospect as I am determined to see the best in New York and already there is a glimmering. I spent 7 weeks in St Thomas’s home with a broken leg – I rented a television and it was a God-send – enabling one to use one’s eyes in another way and so instructive [television was at that time frowned upon by the educated classes and the Lamberts only got a set when Kenneth Clark’s series Civilisation was broadcast in 1969]. The food wasn’t all that good, but we got the left-overs from Matron’s dinner parties, lovely little bits of paté hiding away in rice pudding. I was allowed to keep wine in my wardrobe. I had no religion to fall back on, but telling your beads must be cosy (I always remember with affection the following in a taxi – Me: “Did you see they have found a man left over by the Germans who has spent 11 years alone in the dark, blocked up in a food store? How could God allow it?” You: “He must have wanted to give him time to think.”) I am glad to say that I have a servant to take with me to New York – very rare and distinguished. I forget if you know him; I found him in a mud hut on the edge of the Sahara and brought him to London – he has learnt to cook very well and loyalty and obedience shine like twins in his beatle black eyes. He is immensely attractive to the ladies of London and has two café au lait babies in Camden Town – the slightest indication of the power he exerts on the frail sex. I expect you wish you had bought even more pictures and even more Italian furniture than you did. I hope your daughters appreciate it all. I thought your youngest child about the nicest creature I could remember – so amusing and pretty. … ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Margaret Lambert was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in recognition of her work editing for publication the documents captured by the Allies from the Nazi German Foreign Ministry at the end of the Second World War. This is the account that she wrote of the occasion to her aunt Mary Pring.

Letter 10.19. Margaret Lambert in London to Mary Pring in Tiverton, 7 November 1965

Dear Auntie, On Friday, Guy Fawkes Day, I went to Buckingham Palace with Grace and Enid to be invested with my medal. I expect you will like to hear about it, so I will write while it is still fresh in my mind. We had to be at the Palace at ten in the morning and were instructed that we must wear “Day Dress”. These instructions are, of course, issued for men, because they get most of the decorations. But we took them to mean that we must wear our best coats. I was particularly resplendent in a huge mink hat, which Enid had bought for me for the occasion, and was a little troubled whether, if the medal had to be hung round my neck (as the men wear theirs), it would go on over the hat. But I need not have worried, all was most efficiently arranged. At the Palace we were divided into two groups, “Visitors” with which Grace and Enid went, and “Recipients”, which was my group. I was shown into one of the reception rooms with about a dozen elderly gentlemen, all in morning coats and light waistcoats, except one, who was wearing a dark waistcoat and was rather fussed about it. But the others consoled him. I was amused to see how nervous all the men were. They kept tweaking at their coats and smoothing their hair in the mirrors. There then arrived a very eminent academic lady, Dame Margery Perhamˡ, who was getting a higher decoration than myself. She is a retired Oxford don, and very vague, so she was being shepherded about by one of the Queen’s secretaries. One man got lost, and there was a good deal of fussing about looking for him (whether he was eventually found or not, I do not know). We were then given a lesson in what to do by some of the gentlemen of the Queen’s household. We were told that we must go forward into the Ballroom and stand beside an officer, posted on the left of the dais, on which the Queen would be standing with the Lord Chamberlain. Our full names and the decoration would be read out by the Lord Chamberlain. When we heard our surname (this was the cue, like a stage entry), we were to walk forward level with the Queen standing on the dais, bow, then take six paces towards her, and stand there while she attached the decoration. She might, or might not, say a few words, but would shake hands with each of us. When she shook hands, that would be our cue to walk back a few steps, bow again and walk out. Tall gentlemen were to remember to lean forward so that the Queen could reach to hang their medals round their necks.Gentlemen to be knighted were to kneel with their right knee on a little stool, which would be brought by a page. At this point in our briefing, a stool was brought in and various of the men rehearsed on it. Having got this far in his briefing, the man who was rehearsing us suddenly noticed that two of us were ladies. So he quickly said “Ladies will of course make a curtsy, but not a very deep one”. He then actually made a curtsy of a sort himself, to be sure we understood, and this looked so funny with him in a frock coat that I was hard put not to laugh. He then looked us over again and said “Ladies may either wear both gloves or none, but they should not wear one glove only”. So I took mine off, but kept on my coat, for I thought it is easier to make a curtsy neatly if one is wearing something rather heavy and besides, it was very chilly in the Palace. We were then all lined up in a single file and marched to the anteroom of the Ballroom. An attendant pinned a little hook to my coat to take the medal and told me to be sure to remember to give the hook back as I went out. In the anteroom, there was still a bit of confusion over the missing man, but finally it was decided to let Dame Margery Perham lead us in, then came two men to be knighted and then myself, with the rest of us in line behind. Being in front like that, I was able to watch a little procession of Beefeaters and two Gurkhas in uniform form up on the dais, and then the Queen came in with the Lord Chamberlain and a group of officers in uniform. The Queen was wearing a turquoise blue dress, with diamond clip, which looked very pretty against the red coats of the Beefeaters. The the band, who were sitting in the organ-loft at the back of the Ballroom, played God Save the Queen, and we were sent forward one by one to receive our decorations and, as far as I could see, there were no mishaps to my party. When my turn came, the Queen spoke to me very softly and said “I am so glad to be giving you this. You work in the Foreign Office,” and I said “Yes, on the German documents”, and she said “Of course, on the German documents”, and shook my hand. I then went out and gave up my little hook and was given an elegant black box to keep my medal in and told that I was the first woman to be given the CMG. I was then allowed to go to the back of the Ballroom and sit amongst the audience and watch the rest of the performance. There were about two hundred people in all decorated, and the Queen hung the decorations most carefully and said a few words to each one. At the end came the decorations for gallantry, with two merchant seamen, who were sent in together, a policeman from Manchester and various people from the army, navy and air force, also some from the St John’s Ambulance Brigade. The whole ceremony lasted till twelve fifteen. The Lord Chamberlain, who was holding the decorations on a red cushion and handing them to the Queen, began to look rather tired, but the Queen was bright and fresh all the time. I remembered the Ballroom as the room in which Grace and I were presented [see Letter 2.5], goodness knows how many years ago. And Grace remembered being at a royal ball there when the Duke of Windsor, who was then Prince of Wales, had suddenly walked through in obviously a towering rage. He had wanted Mrs Simpson to be invited, but King George and Queen Mary were not willing to have that, I suppose. At least that is the story that was current at the time. Grace told me that the vistors were marshalled to their seats by a retired naval officer in a loud quarter-deck voice, who said firmly that there was to be no applause. I was very lucky, I suppose, not to be sent for on the day that the Beatles went to the Palace to get their MBEs, when there was a rowdy crowd of teenagers, screaming and shouting outside the Palace gates and having to be held back by the police. The day I went everything was very peaceful and decorous, though there was quite a crowd outside watching the changing of the guard and the cars drive up. We were also very lucky to have a fine day, though a cold one. … My love, Margaret

ˡOxford don and distinguished historian specialising in African affairs. For an account of the similar occasion at which Sophia Lambert was awarded the CB, see Letter 14.18. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Letter 10.20. Michael Lambert in London to Florence Lambert in Corfu, 22 August 1968.

My love, Tremendous activity in the last few days. On Thursday, I had to attend the Magistrates’ Court at Okehampton, where we sat in judgement on the young man who ran into me. (Two of the magistrates were old supporters of Pa’s.) As the young man was 21, wealthy and with two endorsements on his licence, he had to fight the case and for this purpose engaged the ablest lawyer in Torquay. However, after two hours he went down and was fined £20 for running into me and £10 for having defective brakes on his trailer. In addition, his licence was taken away for six months. Most of Friday I was dealing with the problem of finding a suitable site for a chipboard mill. Saturday morning I had an S.O.S. from Pat to entertain the American bishop and his very talkative wife. In the afternoon, there was, of course, the [Spreyton] flower-show. Sophia entered three roses, which got second prize, and a mixture of annuals, which got no prize. On my way back from Exeter, I had another look at that ruined cottage. There is no doubt that it has possibilities: it could be made into a gem. The only thing that worries me is the possibility that it is in a frost hole. Elisabet [the Lamberts’ elderly German housekeeper] told me that one night Flavia lent her key to one of the Italians and then found that she could not climb in. When Elisabet went to investigate, she found Flavia fast asleep in the porch with a lighted cigarette in her hand. It was interesting to read in the paper this morning that even the C.P.G.B. [Communist party of Great Britain] has denounced in no uncertain terms the Russian occupation of Czechoslovakia. The French and Italians, however, got in first. The Chinese said nothing. I suppose this is the end of communism as a world movement. All my love, Michael Florence in Greece 1960s -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.21. Michael Lambert at 2 Aubrey Road to Florence Lambert at the Hotel La Serenissima Terme, Abano Terme (where she had gone with her friend the photographer Lee Miller to take mud baths for a back ailment), 22 April 1969

… Flavia [at University at King’s College, London] is proving an excellent housekeeper and admirable cook. I live in the lap of luxury. Caelia was here last week but has now returned to what I hope are her studies [at Essex University]. Frank [Tuohy] is coming tomorrow night. Vittorio [Flavia’s then boyfriend] was here last night. We do not suffer from a lack of faces. Tomorrow I am having a bit of an outing and propose going over the Tiptree jam factory [which his firm was financing]. I believe it is all rather old-fashioned with vast copper cauldrons stirred by ladies with wooden spoons. It should be quite fun. Alas, time marches on and I no longer eat jam. The weather here has as usual been variable – cold, sunny, warm, wet – in fact, like Tiptree jams, plenty of variety. The camellias in the back garden are in flower, but not the one in front, although the Baileys’ [next door] are. All my love, Michael ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.22. Michael Lambert at 2 Aubrey Road, London W.8, to Florence Lambert at the Hotel La Serenissima Terme, Abano Terme, 27 April 1969

My love, We have quite a party this weekend – Frank, Caelia and her new American boyfriend. I wonder if Tim [her previous American boyfriend] knows. Flavia is doing the housekeeping admirably despite the uncertain numbers for any particular meal. … I am off to Northern Ireland tomorrow for the night. I suppose they will all be very gloomy. There was an interesting interview in the Observer with Bernadette Devlin [fiery Irish socialist republican who had just been elected at the age of 21 as the M.P. for Mid-Ulster]. She seems to be one of the new generation who believe in class warfare and not religious warfare. Class warfare can at least be controlled by improving the standard of life. … Miss Devlin has an admirable cure for the ills of Ulster – a socialist revolution in the South. One can’t help loving Irish logic. However, it is worse in the U.S.A. Caelia’s friend was telling me how the General Electric Co. tried to find a house for a Negro they employed at a salary of $100,000 p.a. outside the Negro ghetto and failed. Only Paisley and Brookeborough [Ulster Unionist politicians of extreme views] would refuse to meet a Catholic earning $100,000 p.a. It will not escape your notice that Brookeborough’s tree died. All my love, Michael ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.23. Margaret Lambert in London to her sister Grace in Exeter, 26 July 1969.

… I have a nice new friend, a lady historian from Kansas, who must return there next week. Actually, she was born in Danzig, brought up in England during the war, went to Canada and put herself through McGill University (working her way not by dishwashing but by selling Bibles for some organisation), taught there for a while and is now in Kansas. She has the same wonderful command of languages as my old friend Sir Lewis Namier¹ had – she says she speaks Russian with a Polish accent, Polish with an English one, French, German and Italian with a Slav accent and English with an American one. She made us laugh when she described being with a party of her students in Moscow when the first Russian cosmonauts were being officially fêted. They managed with much difficulty to persuade their Intourist guide to let them depart from the prescribed itinerary and go to watch the proceedings in Red Square. Her students waved and cheered and she looked round to find that only her students and the Cubans were doing that. The rest of the crowd were bored and glum and had obviously been ordered to attend. In Novgorod she said to a Russian woman “aren’t you glad that your cosmonauts are home safely?” and got the reply “Nichevo, nichevo” (Russian for “couldn’t care less”). That, she said, was the general attitude when you talked to Russians in Russian, as she obviously could do very fluently. …

¹Sir Lewis Namier (1888-1960), well-known historian. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.24. Margaret Lambert to her sister Grace Lambert, Sunday 5 September in the 1970s.

… I am sending you a cutting from today’s Sunday Telegraph. It is an extract from Martin Gilbert’s biography of Churchill and deals with Churchill’s attempt to get Lord Fisher back [see Letters 1.15 to 1.20]. That would be what Ba was corresponding with Sir Winston about in the letter which Mickie remembers to have seen, at Spreyton I should imagine, and probably at the time when Admiral Bacon was writing his life of Fisher [published in 1929]. For, as you will see, it has always been a puzzle why Churchill should have wanted Fisher back, having previously been so cross with him. I don’t think Martin Gilbert is as good a biographer as Randolph Churchill was [the latter had written the early volumes of the massive biography of Winston Churchill that Gilbert had completed]. For Randolph, by skilful weaving, managed to let Churchill speak for himself much more. Whereas it seems to me that there is too much of Martin Gilbert in his version and not enough of Churchill. … In this particular extract, I think a more experienced man would have been careful not to place so much reliance on Ld Beaverbrook – he might have used the quotation, but qualified it a bit. For by now it should be obvious to anybody who knows anything about the subject that Beaverbrook always exaggerated his role and is a most biased witness – one could almost say a notorious lar – where his own vanity is involved. In last week’s extract, dealing with the Fisher/Churchill rumpus and the formation of a coalition government, I noticed another of Gilbert’s little slips, though not due to Beaverbrook this time, or not recognizably so. Gilbert has had access to the Venetia Stanley letters exchanged with Asquith and quotes freely from them [these letters were then unpublished but were published as a book in 1982]. … Gilbert says sweepingly that at the time of the crisis neither Churchill nor Lloyd George etc. knew of the terrible blow Asquith had just suffered in getting a letter from Miss Stanley saying she had decided to marry Edwin Montagu. Now I well remember Ll.G. giving Daddy and me a most spirited imitation of Asquith reading V.S.’s letters during Cabinet meetings and ringing for a messenger to send an answer back. Especially spirited was his imitation of Asquith receiving that particular letter – Ll.G. blew out his cheeks and put his pince-nez on the end of his nose and mimicked Asquith holding the letter close up to his face and then far away, unable to believe what he read in it, and then scribbling furiously and ringing for a messenger. So presumably Ll.G. knew precisely what was happening. The object of this performance was to explain to us that Asquith really was quite unfit to run the war even then – he did not attend to Cabinet business, he scarcely bothered to listen, and what he did take in went straight back to “that woman”, said Ll.G. There was evidently another of these lady friends to whom Asquith was writing in Cabinet during the crisis when Ll.G. ousted him, for we got an illustration of that too, but I don’t think her name was mentioned, or I have forgotten. Dear Gracie, I am running on about nothing much really. I didn’t say anything of it to Martin Glbert. Anyway, Ll.G.’s version will have been very biased. In those days, when he was writing his memoirs, he hated Asquith and so, evidently, did Miss Stevenson [Lloyd George’s secretary and later his wife] who was looking up things for the book. But she said McKenna was the nigger in the woodpile. … All my love, Margaret -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 10.25. Margaret Lambert to Betty, an identified contemporary from Lady Margaret Hall, now living in Birmingham, 15 June 1974

My dear Betty, … The Birmingham Post for Wednesday last, June the 12th … contains a letter by a Reverend gentleman who signs himself as the Professor of Theology at the University of Birmingham (alas, I have forgotten his name). The letter argues for the retention in the syllabus for R.E. (Religious Education?) in Birmingham schools of the Professor’s plan to devote a larger section to Communism (31 pages I think) than to Christianity. From the tone of the Rev. Professor’s letter, I gather that some people in Birmingham have been expressing doubts as to whether Communism is a religion, or indeed a suitable subject for inclusion in a syllabus for Religious Education at all, for he sounds rather cross, as Professors are apt to do when non-Professors have the audacity to disagree with them, and being cross lets fly at his critics in so ludicrous a way that he sounds for all the world like a parody by Peacock of the “March of the Wind” in, say, “Crotchet Castle”. At one point I actually laughed out loud, only to regret it for I am temporarily laid up with so severe a bout of rheumatism that any sudden jerk is very rash. …Would this really produce an “excting new syllabus” (the Rev. Professor’s expression, not mine)? My own, admittedly limited, experience with teaching Political Theory to undergraduates suggests that it almost certainly would not. This is because the Marxist-Leninist scriptures are so incredibly dull that it is virtually impossible to get even university-level students to take an interest in them. For younger children, perhaps one could introduce a little audience participation? But that would necessarily mean playing at the class war, by building barricades and punching each other up, “proles” on one side and “capitalists” on the other, with the risk of children injuring each other, let alone the teacher, and damage to school property. On balance I am inclined to think that, if it is really necessary to make Religious Education courses “exciting” by including pseudo-scientific forms of devil worship, it might be better to take as an example a more manageable type, some natty little ritual that would fit neatly into school timetables. Maybe some form of witchcraft or black magic? There is of course always raising the devil, or trying to, which can be quite an “exciting” performance, to judge by the play “Mr Bolfrey” [by James Bridie, 1943], which not only shows how to set about it, but gives the theological arguments, pro and contra. I remember how, during the war, when I was working with the BBC’s broadcasting service to Austria, we had a number of Austrian prisoners of war who used to do a weekly programme of songs and little plays, which they devised themselves. They were delighted with “Mr Bolfrey”, picked out some scenes and gave such a spirited performance that I still used to get letters about it for a good ten years after they had all gone back to Austria. Finding suitable plays and sketches for these Austrian prisoners of war to perform was quite a business, for we had both Catholics and Socialists in our group and had to avoid anything that might offend the sensibilities of either. The only thing on which they were all agreed was dislike of Hitler and the Nazis and, of course, raising the devil and disputing with him fitted in very well with that. We would also have liked to do “Animal Farm”, but there was some technical hitch about that. I do also remember having an odd experience about devil raising in, of all places, the North Library of the British Museum, where, as you may remember, one had to go to read rare and precious books and was only allowed to take notes in pencil for fear of damage. Besides ordinary scholars, there were, as you can imagine, some very eccentric ones, including some interested in black magic and similar occult subjects. One of these oddities took to experimenting with the recipes given in the books, by making cabalistic chalk maekings on the floor, spreading chalk dust on the feet of other readers. This put the nice superintendent, Mr Ellis, in rather a fix for there was nothing in the printed regulations actually forbidding such activities, presumably because no one had ever imagined they would happen. Finally the ever tactful Mr Ellis decided to tell the culprit that he really must not raise the devil in the North Library, as this would be disturbing for other readers and might lead to breaking the rules about silence. He should do it at home in his own kitchen where he could talk to the devil as much as he pleased. That did the trick and there was no more chalking in the North Library. But I must not run on with these trivialities. The only reason I am venturing to bother you [Margaret wanted Betty to send her a copy of the Birmingham Post] is that I have a serious interest in these ideologies and their capacity for creating illusions in the minds of well-intentioned persons who take them to mean something very different from what they really do. After all, one of the principal reasons why the Second World War was allowed to happen was the confusion created, in most cases quite deliberately by skilful propaganda, in peace-loving democratic countries about the true aims of the dictators, and the true nature of their systems of government. I have often been asked by students how otherwise quite sensible people could so easily have been taken in and there are times when I find it almost incredible myself. So I was specially interested to see that, judging by the Professor of Theology’s letter in the Birmingham Post, the same sort of silliness still prevails among the learned. … Please forgive a rather incoherent and very ill-typed letter. I am doing it in bits as I cannot sit up very long at a time. Besides, there is an intriguing distraction in the street outside – a film is being made for the BBC “Upstairs, Downstairs” programme. There are all sorts of fascinating things – antique buses which can’t be got to start, or if they do run backwards, vintage cars, people in First World War clothes, even a milk float with brass cans (but not polished as I remember them in my childhood). Have you got a telly? If so, look out for a film about a brave bus conductress in the First World War, for that is what it seems to be about. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------