Letter 2.2. George Lambert M.P. at the Hotel de L’Europe, Venice, to his 14-year-old sister Mary at Coffins, Spreyton, Devon, 8 October 1894

My dearest Mary,

You will see where I am by the above heading to the note-paper. We are staying at an extremely swell hotel, one of the best situations on the Grand Canal. We arrived here last Thursday afternoon. I was charmed with the place; it has more than fulfilled all my anticipations. Going about in a gondola is very delightful and not very costly – 10d. the first hour and 5d. for the next. They do not row in the ordinary way, but stand up and face the direction in which the boat is going, pushing and pulling the oar.

Mr Seale-Hayne rather intended to leave here yesterday or this morning, so I hurried over the sights, doing two days in one. Had I known we were going to stay so long, I should have gone about it in a more leisurely fashion. The Piazza of St Mark is the principal square, in fact almost the only one, as the city is one network of small causeways about 6 ft. wide, except the canals, which of course are wider, but then you could not call a space of water a square. The Piazza is lovely, surrounded by superb buildings of great beauty, with the beautiful church of St Marks at one end. One is never tired of admiring it. However, I hope to bring home a photograph so as to give you some idea of it.

It is a queer coincidence, but when we came there were three M.P.s and three officials of the House of Commons in this hotel. Sir William Harcourt [Chancellor of the Exchequer] is here too. It has given us in fact a great deal of amusement, how that first he was at Paris and intended to be back for the Cabinet Council on Friday; then they discovered he did not come, in fact, as I can speak from knowledge, he was far more agreeably occupied in disporting himself in a gondola that day. Oh! those newspapers; what they do print and what people do swallow as gospel. Sir William has invited us to dinner tonight at eight. As we usually dine at 6.30, I am filling up this interval writing to you.

Today we have not been doing much; in fact Mr Seale-Hayne’s foot gave some symptoms of pain and he has I think taken colchicum [a cure for gout] which, while warding it off, leaves you I believe feeling very seedy; at any rate he is not quite himself, being what is remarkable for him disinclined for exercise or going about. In fact he is now talking of going back to Switzerland again. He fully decided two or three days ago to get back by Sunday next, but now he is hesitating what to do, and what he will decide I don’t know. However, we cannot have better quarters; and the weather is simply perfect, sunny without being too hot. We bathed in the Adriatic this afternoon from the island of Lido, just away from here. It was delicious, but I did not stay in for long, having had a cold, which happily is better. I fancy I must have caught it sleeping in a draught.

I must shut this up now, as it is time for me to get ready for Sir W. Harcourt’s dinner.

9 October.

The dinner passed off first rate. Sir William Harcourt, his son, Mr Labouchère¹, Mr Roby², Mr Benson³, Mr Seale Hayne and your humble servant, all M.P.s; it was a miniature House of Commons. It is very extraordinary, all Liberal M.P.s, I do not believe there is a Tory here. We stayed there until quite late, 11.30, then came back and went to bed. It was very interesting and amusing to hear Sir William and Labouchère recalling reminiscences. I shall remember that, on my first visit to Venice, I dined with the Chancellor of the Exchequer. …

All sorts of people are in this place. We have had a delightful row in a gondola this morning to an island called Torcello, two hours each way. We read the Devonshire newspapers in the lovely sunshine, tempered by a cool breeze. … I do not quite know when we are coming back. It was intended to be on Sunday, but Mr S. H. is hesitating about staying longer and cannot make up his mind what to do. I must be home by the 22nd, as I have written to Mr Sanders [probably his political agent] asking him to fit me in for some meetings then. However, I am all right and enjoying myself enormously.

With very best love to Mother and yourself,

Your loving brother,

G.L.

¹ Henry Labouchere (1831-1912). He was from a rich Huguenot family, and was a well-known Liberal M.P., writer and theatre owner. He is chiefly remembered for having introduced the “Labouchere amendment” that made male homosexuality a crime.

² Henry John Roby (1830-1913). A classical scholar, writer and educationalist, he was prominent in the Liberal Party in Manchester and was M.P. for Eccles from 1890-1895.

³ Godfrey Benson, later 1st Baron Charnwood (1864-1945). A writer and philosophy don at Oxford, he became interested in politics and was the (Liberal) M.P. for Woodstock from 1892-95.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.3. George Lambert M.P. at the Gasthof zum Hecht, St Gallen, to his sister Mary at Coffins, Spreyton, Devon, 5 September 1895

My dearest Mary,

I was very disappointed at not getting a letter from you yesterday, but I suppose you thought the letters would not be forwarded so soon.

Well, we are having some blazing hot weather. I wonder what it is like in Devonshire. On Monday, we left St Gallen for a place called Weissbad (pronounce the W as F), precious hot it was too. Tuesday we did have a sweat climbing a mountain, the [?] Hoherkasker. We started at 7 o’clock and reached the top at half past nine. I took off my coat and waistcoat and hung them out in the sun. I dried up my flannel shirt on my back. There was an Inn where we regaled ourselves, Mr Seale Hayne with some soup and I with two very small boiled eggs. On our return to the hotel, a warm bath was a luxurious welcome [it was an area of natural hot baths]. We are in quite a German part, though 'tis Switzerland. The people have a tremendous feed in the middle of the day, called Mittagessen, and then supper at 7. They do eat queer mixtures, too. Monday night I finished my supper with liver and plum jam; and Tuesday with a kind of sausage or mince meat and stewed apples. What does mother think of these mixtures? But 'tis a German tip to have a sweet with the joint. …

What sort of sport are they having with the partridge? … Have you finished harvest? I expect nearly so, now. Is the wool packed? How is everybody and everything? Is Mother very well, and you? All these are queries which are interesting to me, but I don’t suppose I shall have an answer till Monday week. …

With best love to Mother and yourself,

Your loving brother,

George.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The young M.P. was also taken up by the wealthy Earl of Rosebery, one of the elder statesmen of the Liberal Party, and Prime Minister from 1894-5. In the mid-1890s, probably after Rosebery had resigned as Prime Minister, George was invited for the weekend to his house at Dalmeny in Scotland. It took some time for George to lose the sense of wonderment that shows in this letter of the country boy unexpectedly among the swells. Throughout his life, he remained a man of unsophisticated tastes (his main recreations were shooting and golf).

Dalmeny Park

Letter 2.4. George Lambert M.P. at Dalmeny Park, near Edinburgh, to his sister Mary at Coffins, Spreyton, Devon, probably 1896.

My dearest Mary,

You will see by the above [letter heading] that I am got among the swells now. I came here late last night. There was an unfortunate blunder. The secretary of Lord Rosebery¹ wrote to Spreyton instead of to London as I suggested. Lord R’s letter asked me to come by the train from London which got here in time for dinner, but I only got the letter just as I ought to have left, so had to wire, but was however met in Edinburgh, about 5 miles away, at 10.30, and got here about 11.15; had some supper and went to bed.

There are several people here from Saturday to Monday: the late Lord Advocate and his wife; the Lord Chief Justice of Scotland and Mrs Chief Justice; Sir James Carmichael² and wife; Sir J Leng3 M.P. and Mr Mundella4, so it is quite a party. I am here to shoot. Lord Ripon5 is to come on Tuesday; he is a great shot, I believe. What sort of shooting it will be, I don’t know.

This is a beautiful place, close to the Firth of Forth and the Forth Bridge. But another, still more beautiful I think, although much smaller, is a place that was an old ruin but has been restored, Barnbougle Castle. It is full, too, of the most interesting and most valuable objects. Lord Rosebery is very kind. One hardly knows who is who, yet. I was late for breakfast and saw quite a table full of ladies who I didn’t know were in the house.

It is all very swell: four table footmen and a butler, one hardly knows what to be up to, but still, it seems you must do just as you please. I’ve been for a long walk with Ld. Ch. Justice and Lord Rosebery this afternoon, and expect shall get on all right.

With my best love, and hoping you are well,

Your loving Brother,

G. L.

¹ Archibold Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery (1847-1929), Liberal politician. He twice served as Foreign Secretary and he succeeded Gladstone as Prime Minister in 1894 when the latter retired. He owned 12 houses (some acquired through his wife, a Rothschild heiress). These included the large Gothic revival Dalmeny House on the banks of the Firth of Forth and the medieval Barnbougle Castle nearby (which he is alleged to have used for assignations).

² Sir James Carmichael Bt. (1844-1902), Liberal M.P. for Glasgow St Rollox.

3 Sir J. Leng, M.P. for Dundee, a senior Liberal who supported radical social policies and Irish home rule.

4Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897), M.P. for Sheffield. Son of an Italian refugee. Also on the reforming wing of the Liberal Party and a proponent of compulsory education.

5 George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon (1827-1909). Liberal politician who had held a number of senior Ministerial posts.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.5. George Lambert M.P. at the Reform Club, London to his mother at Coffins, Spreyton, Devon, Saturday night undated (mid-1890s)

My dearest Mother,

I went to Brighton [where his sister Mary was at school], and found Mary¹. It was, however, a good two miles from the station, Sussex Square being one of the old squares, at the quiet end of the Town. It is a charming situation upon the slope of a hill, about four or five gunshots from the sea. The houses are like – in fact some of them are – gentlemen’s residences, not unlike Mr Seale-Hayne’s on the outside. …

We walked along by the sea for about two miles, further than she had been before, until we came to a more crowded part of the Esplanade. By that time it was nearly two. I had been asking where she would like to go to have something to eat, and suggested the Metropole, a very large and very swell hotel. She said girls sometimes talked about their friends taking them there. That settled it and in we went into the dining-room, where there were about 50 or so people at small tables, men and women, band of music playing etc., etc., all very grand. She did not seem at all embarrassed, and we had the table d’hôte luncheon, and after went into the conservatory, beautifully warmed, and had our coffee – in fact did the thing in style.

Then we walked about Brighton a little, bought a pair of dancing shoes (6/11d.), some chocolates, sweets etc., had some tea in a shelter on the Esplanade, and got back to the school at a few minutes after five, just giving me time to get my train at 5.45, which landed me at Victoria in time for a 7.30 dinner. … I fancy my going down dressed in the height of respectability will not have lessened Mary’s importance. …

I wonder how you are all getting on. Please let me know about the work, the lambs etc., etc. I expect little has been done, the weather being so severe. I think I ought to have spoken in the House on Thursday or yesterday on an agricultural debate, I got up a speech but did not get it off. I fancy, however, that I have drawn a good place for a Land Tenure Bill for 15th May [George wanted to introduce a Private Member’s Bill to give tenant farmers more rights].

With my best love,

Your loving son,

George

¹ Mary Lambert (1880-1972) was George Lambert’s only sibling. She later married Walter Pring and lived in Tiverton. Letters in Part 3 describe a trip that George’s daughter Grace made with her to the Sudan.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VISIT TO RUSSIA

In 1899, George – as one of the few M.P.s with practical knowledge of farming – was invited along with a colleague who had a big grocery business (Hudson Kearley M.P., later 1st Viscount Devonportt) and the Chief Veterinary Officer of the Board of Agriculture (Professor Curtis Cope) to visit Russia to advise on improving their livestock. He left a detailed diary of his trip (now in the Library of the School of Slavonic Studies), and the two letters below to his sister Mary have also survived.

Letter 2.6. George Lambert M.P. at the Hôtel du Bazar Slave, rue Nicolskaia, Moscow, to his sister Mary in Devon, 17 September 1899

My dearest Mary,

We have just arrived here, having travelled overnight from St Petersburg. It is nothing in this country to travel all night. The place is so big that one hardly knows where is the end of it. I believe we are to go at the end of the week to a place 17 hours away, and then a lot further, so far that it takes 72 hours or three days in the train only to get to St Petersburg and then there are 54 hours to get to London. All this I don’t altogether like; in fact I may go back through Constantinople as it is so much nearer. We shall be very near Sevastopol, where the Crimean War was fought; I want to see that rather. The Ministers here even want us to come back to St Petersburg, in order that they may pick out our ideas of their country and what is wanted to improve it, and as they are paying all expenses, why of course we must fall in a little with their wishes.

I must say, we are being done what is called bravura [sic]. Everything is right up to the mark, and the hotel bills in this country are no trifle; in fact a rouble (2/-) will go just as far as 1/- in England. My two rooms in the hotel in St Petersburg were 28/- a day without food, which would come to at least £1 a day more, but of course everything was done in the most extravagant style.

1.30 p.m.

Now I have had your letter and am glad that you are getting on all right. I was awfully glad to hear from you. I am just beginning to swear again. They want to show us off all round, so there’s no end of things being arranged. We arrived at 11.30 after having been all night in the train, mind. Then there was a déjeuner at 12.30, then at 3 there is some d….d show and at 5 a discussion about an Anglo-Russian exhibition and at 7 a dinner. This is the devil, but we ought not to complain. The Government have sent the choicest wines from the Imperial domain for us, and there’s no end of game. I think they think we are princes, but the lingo is too dreadful for words. Most of them speak French, so if I had not been to Paris, I don’t know what I would have done. Now I’m the best Frenchman of the lot.

This is such a funny town, with iron painted roofs, cobblestone streets, and a great stream of muddy water going down the street and water all about. The climate is so changeful, or we go into so many different climates, that I don’t know what to wear, but have enough.

Will write again soon.

With best love to Mother and yourself,

G.L.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.7. George Lambert M.P. at Vassilyevskoye (the house of his host Prince Shcherbatov, Chairman of the Moscow Agricultural Society), near Moscow, to his sister Mary in Devon, 20 September 1899

My dearest Mary,

I hope you can read the above [address in Cyrillic]; if not, then it is the name of a house

occupied by a Russian Prince. What a God-forsaken lingo this must be when a decent

respectable Christian like your brother cannot even read, much less speak, it.

We arrived at the station and found two troikas awaiting us - i.e. a sort of victoria with three horses abreast. Going out of the station was good, thick, black mud, about six inches deep. After that, it was merely a track without the suspicion of a stone, like going over a wild moor. Here and there were little pools, but no stopping, slapdash through the lot, the horses going like mad and we hanging on like grim death. The Prince and Kearley in one, Professor Cope and I in the other. It was a lovely moonlit night, which made the place look wild, romantic and wonderfully strange. We went along between trees, or rather bushes, which might hold bears, wolves or what not. The horses galloping and the whole thing so strange made it a weird and wonderful ride, like really some pantomimic ideality.

We arrived after five miles to a beautiful mansion designed by an English architect in the Elizabethan style. The hall was hung with carpets and ornaments brought from India by the Prince himself. His wife, mother and sister were there and spoke English thoroughly. In fact the Prince, being a great admirer of England, had a lot of English books and you might fancy yourself in an English house, except that it was deaf-and-dumb show for the servants. I shall be able to run a deaf-and-dumb institution very soon. I know what the word is for a bath, but water, towel and coffee and all the rest is fine expressive gestures.

Moscow is a rare fine old town with any amount of old churches. The minarets shine like

burnished gold. Here are the [illegible] lost by Napoleon; there the cemetery where the people were buried who were killed in the Coronation crush [some 1,400 people had been crushed to death when there was a crowd stampede at the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II in 1896]. Then the images, very ancient and esteemed. The streets are the devil - all cobblestones. Still, it is an eye-opener, like an oriental place which mixes Eastern glitter with Western soberness [rest of letter lost.]

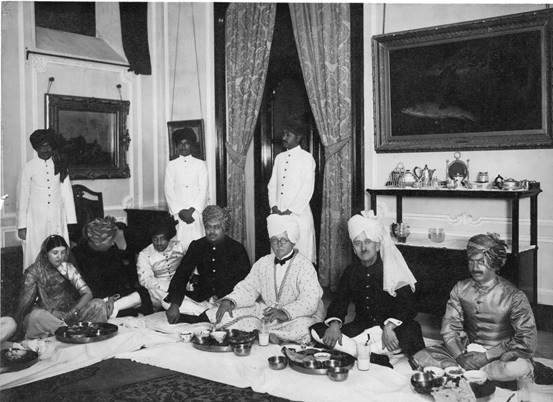

George in Russia (in the bowler)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

LIFE AS A MINISTER

In 1904, at the age of 38, George married Barbara Stavers (also known as Bob or Bobs), by whom he had four children, Grace, Margaret, George and Michael. He remained devoted to her throughout their 54-year marriage and wrote regularly to her whenever he was away.

In 1905, the Liberals returned to power under Henry Campbell-Bannerman and George was appointed to a Ministerial post as Civil Lord of the Board of Admiralty (effectively the junior Minister in charge of naval procurement), despite his lack of any experience outside agriculture – “a farmer at sea”, as the press caustically put it. He remained in that post until 1915. During the latter part of this period, his boss and the senior Minister, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was Winston Churchill, whom George thus got to know well. In 1912, George was also appointed a Privy Councillor (becoming ‘the Right Honourable’), quite an honour for a junior Minister.

On 12 June 1909, King Edward VII held a Naval Review. The Fleet was assembled in the Solent and inspected by the Monarch from the Royal Yacht. As Civil Lord of the Admiralty, George Lambert was closely involved, and sent the letter below to his wife describing the occasion.

Barbara Stavers probably at the time of her marriage

George in Privy Councillor uniform

Letter 2.8. George Lambert M.P. to his wife Barbara, 13 June 1909

… Yesterday morning, it was a damp, dull beginning, but at lunch time the clouds cleared and a lovely afternoon resulted. We got into uniform [as Civil Lord, George had his own naval uniform] and went on board the Royal Yacht. The King shook hands, as also the Queen. The latter snapshotted your husband. In fact she was snapshotting the whole afternoon. We then went up on the bridge and saw the fleet. The Royal Yacht steamed up and down the lines. The Prince of Wales chatted a bit – talked about Grayson¹, the new socialist member.

After the Review, about 4.30, we had tea with Her Majesty at a long table, Queen at head; King at her right; an old lady (I don’t know her name) at the other end of the table. On the old lady’s left sat the cadet Prince [the future Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor, then aged 14] and next the Prince of Wales [the future George V, his father]. I sat nearly opposite the latter. The little Prince is a nice, shy, unassuming little boy, a much finer head than his father. There were lobster, bread and butter, jam etc., and tea. The King had a lobster claw; so did your king. It’s rather a nice relish. The Prince of Wales had lobster, an egg and some jam for tea; in fact he ate nearly as much as his son, who tucked in as befits a schoolboy. The King is very tactful. When shaking hands with Robertson², he said ‘what an excellent speech you made’, whereupon Robertson became a monarchist at once.

After tea there was an investiture. It really was a comic revue – no stage performance could beat it. First some aide-de-camp put all the admirals and captains who were to be decorated in a row and in order. Then a chair was fixed – a dinner-table armchair. The medals were on a table to the King’s right. In front was a blue velvet stand. The officer handed the medal to the King on a red velvet cushion. The recipient knelt on his right knee. The King then tapped him on both shoulders with the Prince of Wales sword – that is the ones who were knighted. Then he put the ribbon, with the cross hanging, on over the head and pulled it down nicely over the neck; then fixed the star straight onto the left breast. Then the honoured one held out his right hand and the King put his hand on it. The blushing possessor then raised his hand, which carried the King’s, back upwards to his lips. The King withdrew his hand; the titled one rose, straightened himself up and left for another to take his place and go through the same ceremony. The unknighted ones did not get the sword taps. The King was so interested in it; did it in so fatherly a manner; it looked for all the world as if he was patting and encouraging a favourite poodle. By the way, there were a couple of dogs scampering about.

Then he bade good-bye; shook hands with the Board [of Admiralty]; said a pleasant thing to each – to me “So glad you were able to come” – banal but gratifying. The Board then sought their barge and the barge sought the Enchantress, which had gone off with the guests on board to let them get their trains. We met our ship coming back; boarded her and changed. I was grateful to get into ordinary clothes, sit down and smoke. We had stood all the afternoon or nearly.

After dinner the fleet was illuminated very finely – the Dreadnought wrongly as her guns were outlined. The signal had been made from the Royal Yacht that the Admiralty flag was not to be hoisted until further instructions early in the afternoon. That was all right while the Board were on the Royal Yacht, but when they were on their own, the flagless ship caused heartburning, so the First Lord [Reginald McKenna, Minister in charge of the Admiralty] wrote [i.e. signalled] to the First Sea Lord [Admiral Jackie Fisher, head of the Navy] on board the Royal Yacht, who said it was a mistake. So now the King has his Royal Standard and the Admiralty flag. We have the Admiralty flag too, so there are two Admiralty flags flying alongside each other. Bunting means a great deal in the Navy.

This morning it was blowing but fine – a pretty sight, all the yachts round, with the big black ships stretching away into the distance. This afternoon we are going to play golf and tomorrow I believe go out to the Dreadnought and see her shoot at targets. Cotton wool in ears is necessary, I hear. …

¹Victor Grayson (1881-1920) was elected as an Independent Labour M.P in 1907 in a famous by-election, at a time when there were very few Labour M.P.s. A somewhat maverick figure, he lost his seat in 1910, and subsequently had drink and nervous problems. He was, however, instrumental in uncovering the “cash for honours” scandal of the Lloyd George government. He disappeared mysteriously in 1920 and it was widely rumoured that he had been murdered to prevent him revealing further corruption.

² Probably John Mackinnon Robertson, the Liberal M.P. for Tyneside.

George (centre) with Admiral Lord Fisher

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

George also undertook at least one official foreign trip as Civil Lord of the Admiralty, to Gibraltar and Malta.

Letter 2.9. George Lambert M.P. on board R.M.S. Otway to his mother at Spreyton, Tuesday mid-day, undated (probably about 1912)

My dearest Mother,

We are now within measurable distance of Gibraltar, about 50 miles, hoping to get in about three. Well, we have had a dusting, a real gale, high seas, generally a sort of feeling that you are in a horrible place from which there is no escape. Friday it was fine, but Saturday morning was unpleasant and developed to more and more disagreeable during the day, while on Saturday night and Sunday morning the sea got very obstreperous. The ship rolled, then rocked, then shook as if it were a bone in the mouth of a big dog. …

Barbara was pretty bad Saturday and had the doctor Saturday night. But after the second dose of medicine she managed to keep things down. The doctor did not come on Sunday morning as he had promised. Poor fellow, he was sea-sick too. However, she got easier, and finally was persuaded to eat some meat – lamb – which filled up the vacuum and she gradually got better – yesterday she ate a lot and today has got up and dressed. … Now she is quite chirrupy and had forgotten it all. I myself was not ill, or I should say not sick, but still felt queer and uncomfortable so, having a comfortable bed, I stayed in bed Saturday and Sunday. We have an excellent cabin, which has been a blessing. But when you get better, you do eat. Bob and I had four meat meals yesterday. The sea is calm now and the weather much warmer – altogether a great change. We have thought of you and the children a great deal and hope they are well and happy and that you are well.

Barbara said, if it were not for the children, I should like to be thrown overboard.

Well, we are now off the ship. The Admiral’s barge came to meet us, to the great excitement of the passengers on board. It was a little rough, but we both managed as if to the manner born. Now we are at the Mount, a lovely place, the residence of the Admiral. You look out of the bedroom window and see the oranges growing on the trees, so you can imagine what it is like. We got here at 4 p.m.; had tea; dined at 8.

Good-bye until my next. Give our love to the children.

Your loving son,

George.

Mind, take care of yourself.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.10. George Lambert M.P. at Admiralty House, Malta, to his mother at Spreyton, undated (probably about 1912)

My dearest Mother,

At last we are in something like comfort. It is good to get clean with no grimy muck such as one collects on railing journeys. We came across from Syracuse in Sicily in great style. Blue jackets waiting at the station to get the luggage; Captain of the yacht in attendance; and as he was able to speak Italian we were in clover. We saw the old Greek temple and theatre, built or hewn out of the rock about 2,500 years ago. Then at 7 o’clock, went on board the ship; had dinner; went to bed and woke yesterday morning in the harbour at Malta. Staying with the Admiral in this house is luxury. It is an old house with walls very thick, therefore cool. The weather is what it might be in the height of summer in England. I am wearing a flannel suit with very thin underclothing and am quite warm enough. The sun is shining brilliantly; not a cloud in the sky.

Of course we are treated with great style. Dined with the Commander-in-Chief last night; dine with the Admiral Supt. tonight; and lunch with the Governor tomorrow. When I am going to do any work, I don’t know. One thing: there are no decent things to buy so there will be no money spent on curiosities. We have some news, too. I see the suffrage bill [probably the 1912 Conciliation Bill to give voting rights to women] has been defeated and the women are burning down places. I wish you were here for a week; it would clear away all your bronchitis in this sunshine.

Give my love to Mary and my regards to Walter [his sister Mary’s husband]. I shall be very glad to see you all again.

Your loving son,

George.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In January 1912, George and Barbara went on holiday in southern Spain, visiting Seville, Granada and Cordoba. They were very impressed with the Moorish monuments, but less so with modern Spain.

Letter 2.11. George Lambert M.P. at the Hotel Oriente, Cordoba, to his mother in Devon, 12 January 1912.

My dearest Mother,

We have come here from Seville today. Curiously enough, we had two wet days there, which is very exceptional in that part of the world. Yesterday, at the instigation of the Consul, we went down to see Sherry made. The consumption of sherry has gone down, so the people are not nearly as rich as they were. We drank sherry of all sorts of ages. It is very good. We were entertained by a family called Buck who were in the wine trade and are English but have been in Spain some 40 years. The old gentleman has written a book on Spain which I must read when I get back.

There is only one thing to see here, and that is the Moorish mosque, which is the most wonderful place in Spain. They have spoilt it by putting in the middle of it a Catholic church. However, we can tell you about it when we get back as it is almost indescribable on paper. I bought a photo just now which will clear it up a bit. One thing: we are on our way home, as we take the train at 11 o’clock and travel by night to Madrid, which we shall reach, all being well, tomorrow morning. This town is not very attractive – narrow streets, cobblestones, smells, etc. …

Spain is about where England was about 100 years ago, except that they have the priests here, and they keep things back, but the working people take very little notice of them. Probably they will get enlightened and the priests will go. Then Spain may go ahead.

Give our love to the children, and we shall be glad enough to see you all again.

Your loving son,

George.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1913, George and his wife were invited for a trip off the coast of Scotland in the yacht of Lord Pirrie, Chairman of the shipbuilders Harland and Wolff (builders inter alia of the Titanic). As the Minister with responsibility for naval procurement, George was obviously seen as an important contact by the shipbuilding industry – although, until the First World War, Pirrie made a point of not tendering for Admiralty contracts.

Letter 2.12. George Lambert M.P. on board the S.Y. Valiant, off Oban, to his mother at Spreyton, 25 August 1913

My dearest Mother,

Life on board a yacht is very curious: you have nothing to do and you do it. Effort seems entirely outside the bounds of possibility.

Well, we are having a most interesting time and – now as I’m becoming more accustomed to it – a very enjoyable one. This yacht is most luxurious. Bob and I have a bedroom as large as at Spreyton, with a bathroom attached. The food is most luxurious and the meals overflow with champagne and cigars, so that really one’s only trouble is to keep oneself from eating and drinking too much. Lord and Lady Pirrie¹ are most kind and considerate. He is a wonderful man – does everything by the most exact method, is very energetic, so energy well directed has raised him to his present position as running probably the finest shipbuilding yard in the world.

Sir Saml. Evans², the President of the Divorce Court, has been one of the party. Dr Freyer³ also; he operated on Lord Pirrie for the same complaint [prostate] that father suffered from and which obviated the use of the catheter. Sir Anthony Weldon 4, a very nice and gentlemanly Irishman, completes the party with your son and his wife. I don’t quite know when we shall leave for home. I am rather longing to, but Bob is sleeping well and is ever so much better. Therefore, we may not be back for 10 days or more. Anyhow, I’m glad you are all keeping well. …

¹William Pirrie, 1st Viscount Pirrie (1847-1924), married to Margaret Carlisle, a well educated woman who took an interest in her husband’s business. Pirrie joined the Northern Irish firm Harland and Wolff (then the world’s largest shipbuilders) as a “gentleman apprentice” and rose to become first a partner and then its chairman from 1895 to his death. A strong supporter of the Liberal Party.

² Sir Samuel Evans (1859-1918) was a lawyer and Liberal politician. He was the Solicitor-General under Campbell-Bannerman and Lloyd George from 1908 to 1910 (when George Lambert was also in Government), but then left politics and became President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty division of the High Court.

³ Sir Peter Johnston Freyer (1851-1921) was a distinguished surgeon known for his pioneering work in effective prostate surgery.

4 Sir Anthony Weldon (1863-1917) was an Irish Baronet. At the time that he was a fellow-passenger of George Lambert on Lord Pirrie’s yacht he was State Steward and Chamberlain to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, having previously been a regular soldier.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.13. George Lambert M.P. at Bertolini’s Palace Hotel, Naples, to his mother at Spreytonway, St Germans, Exeter (the home of her daughter Mary), spring 1913

My dearest Mother,

I am glad we came, since Barbara wanted a change from being always bothered with children. She is much better already. Indeed, I am not sure that she is not infected with some of the Howard bacillae [his energetic mother’s maiden name was Howard], she is so keen on gadding about.

Today has been most interesting, tho’ a little fatiguing. We have been all over Pompeii and thanks to my being a Lord of Admiralty, Rt. Hon and M.P., a special permit was granted for the new excavations, where one gets a vivid idea of what happened some 1,830 years ago. The whole town was overwhelmed and overlaid with about 20 ft. of pumice stone and mud. It was extraordinary to see them excavating the rooms and piecing together the remains of the decoration etc. It was really wonderful to see a leaded copper [pot], not unlike your washing copper at Spreyton, used for heating water. The lead pipes too were not [illegible] but hammered on a piece of wood, so there is a long continuous join at the top. It all is very wonderful; the rooms of near 2,000 years ago have been as it were petrified so that there has been no restoration nor alteration. I am glad to have seen it once again.

The Italian girls are very pretty and Barbara has discovered likenesses to Margie [their second daughter, who was dark-haired] amongst many. We have had heavy rain, so it may be better in Exeter.

Your loving son,

George.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.14. George Lambert M.P. at Bertolini’s Palace Hotel, Naples, to his mother at Spreytonway, St Germans, Exeter (the home of her daughter Mary), spring 1913

… This afternoon we saw the villa¹ that Lord Rosebery had bought. He lived here for a short time. Indeed, he came here directly after he urged the Liberal Party to spade work. Now, apparently tiring of a beautiful spot, he has given it as a summer residence for the Ambassador at Rome. The villa itself has a unique situation. From one part of the grounds you see Sorrento, Vesuvius and Capri without a sight of Naples; from another part you can look straight into the town and harbour.

My first schoolmistress at Spreyton taught me to promounce Vesuvius as Vesuvius. I fancy she was called Harvey or Hill; at any rate she was at Spreyton when I first went there with Mr Nicholls. I must say through it all that, though I like to have seen these places, there’s no place like home, especially if you have children there.

Give my love to all.

Your loving son,

George.

¹ Lord Rosebery (see note to Letter 1.4) purchased the neo-classical Villa Delahante at Posillipo on the Bay of Naples in 1897. It subsequently became known as the Villa Rosebery. He gave it to the British Government in 1909 and it was used by the British Ambassador in Rome. It was donated to the Italian state in 1932 and is now used as a residence by the President of Italy. The reference to Rosebery urging the Liberal Party to spadework probably refers to a famous speech he made in Chesterfield in 1901.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

LEAVING OFFICE

In May 1915, after the failed offensive at Gallipoli caused a split in the Cabinet, both Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) and Admiral Lord (Jacky) Fisher, the First Sea Lord, resigned, as did George Lambert, who went back to being a back-bencher. Another controversial naval move was the removal of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe from the command of the Grand Fleet in November 1916.

In December 1916, the Liberal Government of Herbert Asquith also resigned and was replaced by a coalition Government under David Lloyd George. Lloyd George immediately offered George Lambert another Ministerial post as a junior Minister at the Board of Agriculture. George was a close friend and admirer of Admiral Fisher, whom he felt had been wrongly forced out. He therefore refused as a matter of principle to join Lloyd George’s government unless Fisher was brought back. This is the exchange of letters that he had with Lloyd George.

Letter 2.15. David Lloyd George, Prime Minister, at 11 Downing Street to the Right Hon. George Lambert, M.P., 11 December 1916.

My dear Lambert,

Would you take the Under-Secretaryship at the Board of Agriculture? I am very anxious you should join my administration, and could have wished a post more fitted to your position in the House and to your abilities were at my disposal to offer you. But there is great work to be done in agriculture, and a partnership between you and Prothero [President of the Board of Agriculture, i.e the senior Minister] would achieve I feel confident great results.

Unfortunately, I am laid up and cannot see anyone today.

Ever sincerely,

D. Lloyd George.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.16. George Lambert at 34 Grosvenor Road, S.W., to David Lloyd George, delivered personally 4 p.m. to 11 Downing Street, 11 December 1916.

My dear Prime Minister,

May I as an old comrade in arms congratulate you! Your success means national triumph. May Providence give you strength!

Your wish for me to join your administration I deeply appreciate. Willingly would I do so, but my Admiralty experience bids me regard with grave misgiving Sir John Jellicoe’s removal from the Grand Fleet¹, more especially as his successor was not his choice. Further, I regard it as vital that Lord Fisher’s² unique naval genius should be utilised in actively directing Naval affairs at this crisis. Could you reassure me as to these points, I would willingly sweep a crossing for you, but if not, then it is a real and keen regret to me not to be able to join the administration of one for whom I have ever had so great an administration.

Believe me,Your, etc.,

George Lambert.

¹ Sir John Jellicoe, later 1st Earl Jellicoe (1859-1935). He commanded the British Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 and had been criticised by some for his handling of the battle. He was relieved of his command and appointed First Sea Lord instead.

² Admiral Lord “Jacky” Fisher (1841-1920) was one of the most important figures in British naval history, responsible in particular for improving naval gunnery. He was First Sea Lord (head of the Navy) from 1904-11, when he retired aged 70, but was recalled to the post in 1914 after Prince Louis of Battenberg (subsequently Mountbatten) had to resign because of his German name. Fisher resigned in 1915 after acrimonious arguments with Winston Churchill, the First Sea Lord, over the Gallipoli campaign. George Lambert was a friend and great admirer of Fisher. Fisher appointed George and his friend the Duchess of Hamilton as his joint literary executors. The executors placed Fisher’s papers (including correspondence with George) in the archives of Churchill College Cambridge.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.17. William Sutherland, Lloyd George’s Private Secretary, at 11 Downing Street S.W.1 to the Right Hon. George Lambert M.P., 11 December 1916

Dear Mr Lambert,

Mr Lloyd George asks me to thank you for your very kind letter of today. I am to state that no person has such a belief in Lord Fisher as the Prime Minister has, and he is fully alive also to the importance of the other point you are so good as to make.

In these circumstances, there would appear to be no obstacle in the way of your accepting the position in the Government; and I am to add that Mr Lloyd George is very anxious that the Government and the Nation should gain the advantage of your valuable services.

Yours faithfully,

William Sutherland.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.18. George Lambert at 34 Grosvenor Road, S.W. to the Prime Minister, 12 December 1916

My dear Prime Minister,

The naval position is full of peril. The man to help you save the situation is Lord Fisher. Fate has kindled in both you and him the divine spark of Genius. Bring him in and I’ll serve you in any capacity.

Full of gratitude for your kindness.

Believe me

Yours very sincerely,

George Lambert.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

George discussed his position with Lord Fisher, who clearly thought he was being unduly altruistic.

Letter 2.19. Admiral Lord Fisher at 36 Berkeley Square to George Lambert, 12 December 1916

My dear Lambert,

I’ve slept over our talk of last night and still think you should accept office as you’ve made your protest in writing to Lloyd George and he owns up in his reply that he knows your facts! So I hope you will accept or I shall ever more have a burdened conscience!

Heaven bless you.

Yours,

Fisher.

It really is a pity I can’t put my plans in operation! But I must have Power!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

George, however, was determined to stand on principle and did not accept office. He was never again a minister but became an independent-minded and out-spoken back-bencher, clearly a Whips’ nightmare. He was also active in the internal politics of the increasingly fissiparous Liberal Party.

This next letter appears to have been written later on the same day as the one above.

Letter 2.20. Admiral Lord Fisher at 36 Berkeley Square to George Lambert, 12 December 1916

My dear Lambert,

Your goodness to me is very wonderful. But I think the nobility of your act in refusing office on the public ground of the Naval Peril is a Bigger Thing than the act of your Private Friendship towards me! The Question is now “Can it be dealt with in Time?”.

Yours for evermore,

Fisher

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A TEMPORARY SPELL OUT OF PARLIAMENT

The general election of 1924 saw a big swing against the Liberals. At the age of 58, and after 33 years in Parliament, George lost his seat. It was a big shock, as the seat was thought to be a safe one – indeed, there is a suggestion that his defeat was partly due to complacency on the part of the local Liberal Party, which had done little campaigning. He was re-elected at the next General Election and remained in Parliament until 1945, when he was elevated to the peerage. The following is a letter that one of his party workers sent him, describing the scene in the main square where the Liberal supporters normally gathered to hear the election result and congratulate George on his victory.

Letter 2.21. Mr Palmer at the Rt. Hon. George Lambert’s Committee Rooms, to George and Barbara Lambert, October 1924.

Dear Mr and Mrs Lambert,

I hardly know how to write to you, but I feel that such an occasion could not be allowed to pass without expressing how deeply Mrs Palmer and myself feel the blow which fell upon you and Mrs Lambert yesterday.

We could not believe that such a catastrophe could have befallen us, and how I was kept from a total collapse is a mystery, but I even declared the sad news of our defeat in the square, where there were crowds of people awaiting the news, and it absolutely dumbfounded them all.

The scene in our square all the evening was uproarious and, when Drewe [Cedric Drewe, the successful Conservative candidate] came and went into the Market Hall to speak from the window, the crowd would not let him do so and ultimately he gave in and addressed his supporters in the Hall. Then the Hall windows were broken by missiles from the crowd and Drew ran away, without any hat, surrounded by women, to the Globe Hotel, where he spent the night.

There have been interesting happenings, but I will not tire you now. We should not be afraid to fight the election over again next week and, if we did, we should reverse the majority. It is after all not surprising that we have lost when we see that the tidal wave has swept all the best men off their feet. But in my opinion, we ought to have withstood even that.

We hope there may be an opportunity to have a little chat after you have had a good rest; and don’t forget that our little hut is always open to you and yours at any time. Mrs Palmer is very sorry that you had to have your cup of tea in such a rude manner on Wednesday.

We of course only accept this as a temporary setback and shall look forward to redeem our characters and reinstate you as our member again. So Cheerio. We did not let you down in our area, but never mind; look forward to victory again. Up Lambert.

With my sincere sympathy and a longing hope to be able to shout the song of victory once more in the near future. Mrs Palmer joins me in every good wish to you, Mrs Lambert and family.

Yours sincerely.

L. Palmer

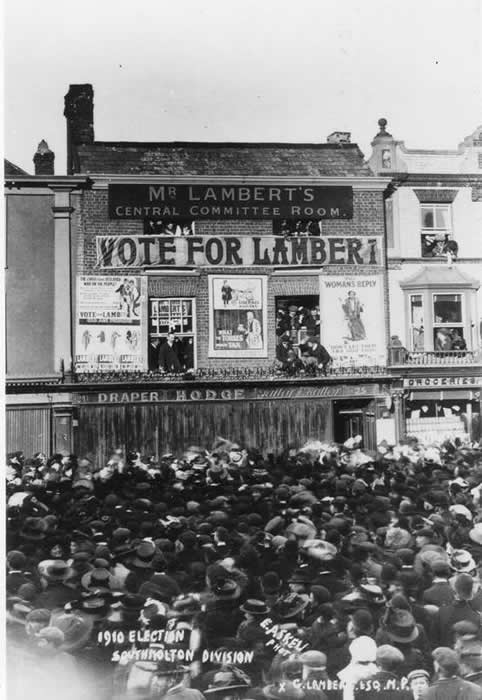

The scene in the square at South Molton in 1910, when George won.

He is at the window on the left.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VISIT TO INDIA

George was re-elected at the next election, four years later, and never again lost the seat. During the time that he was out of Parliament, he had leisure to travel more widely, and in December 1925 he went on a three-month trip to India. The purpose of the trip is not clear, but he seems to have had an invitation from the Tata Iron and Steel Company. He was also invited to stay by Ranjit (“Ranji”) Singhji, the Cambridge-educated Maharaja of Nawanagar (one of the smaller princely states), a famous cricketer who played for England and who was much fêted in Britain. George travelled to India by steamer, a journey of three weeks and his first long-distance sea voyage.

George in India, second from right, next to Sir Edwin Lutyens

Letter 2.22. George Lambert in the Red Sea, on board a P&O steamship en route to Bombay, to his wife in England, 12 December 1925

My darling,

No one could imagine the changes of climate. It is hot, very hot. I’m wearing white ducks, silky brown shirt and flannel coat – still hot and perspiring all over. Indeed, it makes one hot to sit down and write. This will be posted at Aden. There are some nice people on board when you come to know them.

Ranji has asked me to stay with him. I hope to go there the second week in February and come to Bombay in his steamer. His state is by the Gulf of Kutch, north of Bombay. ‘Nawanagar’ is the name – I’ve had to look it up. You cannot remember these crack-jawed names. A young man from Thorneycrofts is going there about some work, so he wants me to give an unprejudiced opinion to Sir John¹, when I get back. I think it will be interesting. ...

Last night I went up with the Captain and had coffee. There was an old General there too. The Captain was in the Kent, a cruiser, at the Battle of Falkland [a British victory over the Imperial German Navy in 1914]. He enjoyed it… [part of letter missing].

I have been away a week and two days. It seems funny. How I should like to look down on you for an hour. I don’t think I will go away again. We’ll motor about. … I’m taking a biscuit for tea – a lot of little, very little, meals are better than three big ones, I find, and there are enough meals in all conscience: 7.30 early tea; 9 breakfast; 9.30 sandwiches. I’ve cut out soup and sandwiches so far. Your forethought in medicine has been most useful. Thank you, darling. In fact all your suggestions have been most welcome.

We are now nearing the bottom of the Red Sea, just past twelve rocks called the twelve apostles. The sun goes down almost flop – you see it on the horizon; then it is gone. One sleeps without anything on the bed – simply lie on the bed in ´jamas. It’s a long way down the Red Sea. We left Port Said at 2 p.m. on Wednesday and arrive at Aden on Saturday, but letters have to be posted before we arrive there to catch a boat back. … How I long to be back with you – you would not credit it. Still it will be an experience. It’s hard to get novels to read on board – there’s a rush for them. But you really can’t do much on board – somebody is always distracting your attention. I’m now going to lie in a salt-water bath – unless one goes early, there’s no chance of getting one.

Bah! The sea water is salt – I got a mouthful and had to smoke a pipe to get the taste out of my mouth. Behold me now, sitting in my cabin – a small one, but big enough – porthole wide open to the sea, with only my jaeger vest and pants on, writing this. Of course there is a sound of voices; I reckon there are four women within 6 ft. of me, but nobody takes any notice. You meet women, men in various states of déshabille. Oh! it’s such a comfort to have a cabin to oneself. I wouldn’t mind if you were here.

Sir A. Gibb² – the man who built [the naval dockyard at] Rosyth – is here, going out to look at all sorts of things for the Government. He and I get on well. Indeed, I saved him when I was at the Admiralty, as Winston wanted to let it drop and I got Fisher to back me – if I had not, he would have busted.

No news of the outer world, except a wireless which has only drivel. Franc down to 131 and Queen Mary advocates Empire shopping. I really am very well; I keep off meat and liquor. I had a bottle of whisky – 7/6d – to start with and am glad it is finished. For lunch I had macaroni, custard, gruyere cheese and Perrier. One’s nails grow very fast; so also hair, or at least seems to. My bill for drinks and cigars was 19/6d for 7 days – it won’t be so much next week. I’ve worn the topé [solar topi] only once, but it’s a good one. They have awnings all over the decks and a canvas swimming bath – about the size of the library – outside Simon’s³ porthole, at which he is wroth.

I don’t know how long we stop at Aden. I shall go off if possible – the topé will be needed. A newspaper in India has sent a bundle of papers, so it’s known that I am coming. How glad I am to be out of the House; it lowers one’s importance but raises one’s freedom.

Darling, I’ve no more to say except that I should dearly – oh so dearly – love to see you and the children. Give them all my love. I so constantly think of you all and wonder what I can bring back for you.

Good night my dear one; may God bless you all.

Your loving George.

¹ This could be Sir John Isaac Thorneycroft (1843-1928), the founder of the Thorneycrofts shipbuilders company, or more probably his son Sir John Edward Thorneycroft (1872-1960) who was managing director of the company from 1901.

² Sir Alexander Gibb (1872-1958), Scottish civil engineer. He first joined his father’s company, Easton, Gibb and Son (which was responsible for building the naval dockyard at Rosyth between 1909 and 1916), and then went on to found his own company Sir Alexander Gibb and Partners in 1922.

³Probably Sir John Simon, later 1st Viscount Simon (1873-1954), with whom George Lambert appears to have been travelling on the journey to India. Simon was one of the grandees of the Liberal Party who occupied several senior Ministreial posts. In 1927 he chaired a Commission on Indian constitutional reform.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.23. George Lambert on board a P&O steamship en route to Bombay, to his wife in England, 17 December 1925

My darling,

We are nearing the end of the voyage. Tomorrow at 6 a.m. we arrive. We are before time, so the ship has slowed down. Consequently it is jumping. Curious that a ship has a speed at which she goes smoothly – we are now doing 15 knots; the smooth speed is 17. By the wireless there are blizzards in England. Here it is beautifully warm and one is fanned by a delicious, gentle, warm breeze. The sea is a wondrous blue, smooth, reflecting the blue of the sky. There is not a cloud. It is a lazy, luxurious existence – rather boring, but it is astonishing how time passes. You sit back and talk and loaf. But it’s dull and one will be glad to be off doing or seeing something. Bombay will be hot but cool at night, I hear.

I am going to stay at the Taj Mahal Hotel with T.S. Peterson [The Manager-in-Charge of the Tata Iron and Steel Works]. [word missing] wrote that he would put me up, but could not take all, so I said – and T.S. was glad, I think – that Mrs T.S should go to Mrs Peterson, as Peterson won’t be back until the 21st. The Viceroy is seeing the Tata Steel works and Peterson has to be there.

I enquired about Oxford Colleges [possibly for his 16-year-old son George junior] of an Oxford don called Carter from Christchurch College. Of course he cracked up his own, but spoke highly of New College. He said if you keep the boy during vacation and pay an occasional tailor’s bill, £350 is the sum for him, but “For God’s sake don’t give him a motor car”. He’s a rum old chap – has a fund of stories. Birkenhead¹ was at Oxford; he dined well – 3 or 4 whiskies and soda before dinner, then liquors as well at dinner. Nine times round the quadrangle was a mile. F.E. challenged the best runner: he would go round five times to the other’s nine. “To show my contempt, I will have a whisky and soda before starting”, he said. “I mixed him one,” says Carter, “and it was one. I thought he would fall down – not he; he ran and won.” …

Ranji says the Hindus won’t take life, not even a bug’s life. They could grow tobacco, but won’t since the plant has moths which the religion precludes killing. In fact there is one sect, the Jains, that preserve even fleas and send for a hindu who, for half a rupee, sleeps there to give the animals a feed. It’s incredible, but I shall see.

I have not heard whether Margy [George’s younger daughter] passed [probably the exam for Oxford]. I expect the wire is at Port Said and came after we left. I hope she has, for she has tried; if she has not, never mind; she can go through next year. …

As I write, luggage is coming up from the hold: gin casks, baggage, all sorts of impedimenta. The poor babies on board have a bad time. There’s never any use for them. They are too tired to lie down and sleep – poor pale little mites, and the mothers get more haggard. One mother I heard say Captain Somebody has taken John for an hour. She looked too grateful. I’m glad our lot are grown up. Now, darling, I’m going to close and do a little packing. I do hope, dearest, you will all have a good time [the family were off to Switzerland on holiday]. I think of you so often. It’s lonely indeed without you.

Your loving George.

¹ F.E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, Conservative statesman and lawyer, well-known for both his hard drinking and his wit.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Tata Iron and Steel Company was founded by a Parsee businessman, Jamshetji Tata, and began operating in 1907. As Tata Steel, it is now one of the largest steel companies in the world. Jamshetji Tata died before the company opened, and it was subsequently developed by other members of his family, including his cousin R.D. (Ratanji Dadabhoy) Tata with whom George had breakfast. B.J. Padshah, another Parsee, was its Director-in-Charge from 1907 until 1924 (and was the man responsible for its early success), and John Peterson took over from him, although it seems from this letter that Padshah was still active when George was in India.

Letter 2.24. George Lambert c/o the Tata Iron and Steel Company, Bombay House, Fort, Bombay, to his wife in England, 21 December 1925

My darling,

Here I am! Mr Padshah met us on the boat. I went to Mrs Peterson, as Peterson was receiving the Viceroy at their ironworks [at Jamshedpur in the eastern state of Jarkhand], but in the evening I came back to the hotel and am now staying at the Taj Mahal hotel with T.S. and daughter. It is much more convenient and quite comfortable for India. I have a beautiful room overlooking the sea and facing east and the sunrise. Of course it is all different, so different, tho’ there are a lot of British at the hotel. The whole thing is too much of a contrast to write about. Fancy, the bearer I’ve got laces up my shoes. The domestic servant difficulty does not exist here. But it’s an enervating climate – delightful in the morning but devilish hot in the afternoon. Of course no rain, always sunshine. One has to be careful of food, not to eat too much.

The contrasts here are far more striking than London. We breakfasted yesterday at R.D. Tata’s on the Malabar Hill. The house must have cost £100,000 if a penny. They call it a bungalow. Marble floors, teak wainscoting. Then on the other hand the most abject poverty. You can’t describe it – motor cars and bullock carts and even bullocks [on the roads]; people crowded in the smallest hovels. Bombay is a very dear place – rupee [supposedly worth] 1/6d. [actually] equals about 1/- in England. I wanted Murray’s Guide to India – 21/- in London; 21 rupees (i.e. 31/6d.) here. However, it’s a change, all of it.

I was awfully pleased to get your wire about Margy; providence is good to us, darling. You are now in the thick of packing for Switzerland. Mrs Peterson is awfully pleased that you are taking her boys with the party. She wants them to be careful too. The maternal anxiety.

22 December.

I have received a wire from the Viceroy asking me to go there. I shall leave here on Thursday. The trip seems to be broadening out. There is a dinner for the Devonians in Bombay. I have written to the Secretary. It is at the end of February, just when I am going back. Tomorrow, we are to go to a wedding; I enclose the card. From my window at the Taj Mahal Hotel there is a lovely sunrise; it rises red, spreading a rosy pink over the hills, and then gets white and hot. …

23 December.

All the times o’clock are different, but at this moment I think you are speeding on your way to Switzerland and tomorrow I am going to Calcutta at the invitation of the Viceroy, so ought to have a decent time. I hope, old girl, you are well. I have been awake since 5.30 and thinking of you and how you are…

24 December.

Last night Peterson came back and advised me to be vaccinated, so I had it done at the hospital and missed part of the Parsee wedding, but I was there at the reception. I shall be pretty bad in about a week, but it’s better than smallpox, which is about, though not general, I believe, but if you saw how people live in the poorest quarters, you would wonder they did not all die of the plague. [Rest of letter missing.]

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.25. George Lambert at the Viceroy’s Camp (in Calcutta) to his wife in England, 26 December 1925

My darling,

I left Bombay at 2 p.m. on the 24th and spent Xmas day in a train across the plains of India. Though it’s about 12 hours of daylight, I was interested in every minute – seeing the native villages, the cultivation, the little patches of rice, everything. I had in the carriage a sea captain in command of a merchant ship in Eastern waters, so it was very agreeable.

Then, at about 7.15 this morning, I was met by the Viceroy’s A.D.C. and whisked away in a motor car while my ‘boy’ was left in charge of luggage. That came and I changed into blue and was driven about Calcutta. At one o’clock, at lunch, I met His Ex. (Lord Reading)¹; he was agreeable – very – then to the Calcutta races close by – an enormous crowd on a great level space. It was Viceroy’s Camp day, so all was state. First Lord Lytton² (Governor of Bengal) and wife with his bodyguard of 100 sepoys all in scarlet; then the Viceroy with his bodyguard drove up to the stand. It was a tremendous ceremonial. Trumpeters, band and all dressed with Eastern gorgeousness. You looked over the great crowd of people of all colours. These were not as bright since mourning [probably state mourning for Queen Alexandra, the Queen Mother, who had died the previous month] is very strict and I had like the others to don a black tie. Anyhow, it was a very wonderful sight. Actually, one of the bookies came all the way from London in our ship to be present at the races. It’s my second race meeting; the first was at Bombay. Really I was fortunate, for it was one of the great social events of India…

I wish, darling, you were here. I feel a bit lonely. I went into Cooks to arrange a tour for myself. I shall be for 10 or 11 weeks all alone. … However, I shall see it through somehow. I expect to be a bit bad with vaccinations in about three days, but must put up with it. It will be interesting, but dull without my dear one. Why did I ever go away from her? Terrible to be homesick, isn’t it? What if I had been a Bachelor? What a fate you saved me from.

This is really a wonderful country – a monument to British genius for governing. Reading is pleased with himself and Lady R. frankly likes the pomp and ceremonial – it has greatly helped her to get better. The curative effects of red carpets. However, there it is – a vast population governed honestly by a handful of English. The Indian legislators – by the Montague scheme [the Montague-Chelmsford reforms of 1919 had introduced a limited degree of local democracy] – are gentlemen given to lining their own pockets. Padshah, who is really a fine Indian, expressed admiration for Baldwin because he, although interested in iron, had refused a duty on iron and steel. I told him that British politicians did not go into politics to line their own pockets. The Indian is the reverse – so good-bye to pure government if the native gets control. …

I’m sleeping in a room about 20 ft. high and 20 ft. square – an enormous chamber. I had a blanket last night, while at Bombay I had a fan and only a sheet. It is not colder, only cooler. There is no cold, except that it’s a bit treacherous at night. I’m sporting my new grey suit today, and went out to see the golf links this morning and a polo match this afternoon, so Sunday is gay. …

28 December.

No letter from you, old girl. I should have liked to hear, but probably the thing has gone astray. I had a sweet one from George [his elder son, aged 16], a really lovely letter – I know it by heart. Now darling, I’m off to Darjeeling – amid the snows to look at Everest and other snow mountains. …

All my love to everybody, including my darling,

George

¹ Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading (1860-1935) was a barrister and Liberal politician who occupied a number of senior positions and was Viceroy and Governor-General of India from 1921 to 1926. He married Alice Edith Cohen, who was a chronic invalid.

² 2nd Earl of Lytton (1876-1947). Son of a former Viceroy of India. Governor of Bengal 1922-27.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.26. George Lambert at the Hotel Mount Everest, Darjeeling, to his wife in England, 30 December 1925

… This is 9,000 feet high and the railway has wound its way all up from the plains. It is a timely journey. I left Calcutta at 9 last night; was routed out at about 5; changed trains; and changed trains again at about 11. Got here at 6 p.m. and I’m wearing the same clothes that I left you in, so you can imagine the temperature. The guide-book warned of a change, so I shifted from flannels into thick clothes – thick overcoat and hat. It’s a wonderful journey up. The train is continuously looping the loop; you look down and see the line below you on the slope.

I have now had my dinner. It is only 9 o’clock and I look out over the town speckled with electric lights. The people here have a Chinese cast of face and appear far more hardy than down on the plains. I have seen tea plantations – one third Horning [a brand of tea] and two-thirds Darjeeling, as Tommy Lough [unidentified] used to say. The tea grows on the side of the hills – a little bush which is pruned every year and the young shoots that come out are gathered to make the tea that cheers the heart. By the way, I forgot, at the station – Parbatipur – where I was routed out this morning, there were lots of dogs sleeping all about. … Further up, there is a forest with tigers and leopards and such agreeable quadrupeds.

Old year’s end 1925.

I have had a great morning. Got up at 3 a.m.; rode to the top of Tiger Hill seven miles in moonlight; waited for sun to rise on Mt Everest. The sun rose red, very red, then picked up the tops of the peaks – really indescribably beautiful – and at last lighting up Mt Everest 170 miles away. That peak did not appear so large, being so far, but Kanchenjanga, 28,146 feet high, is only 47 miles – jagged and precipitous. I am looking at it as I write. Stupendous and splendid. This is really the finest view in the world.

The women do the hardest work. You see them carrying maunds [wicker baskets] of coal or stone by a band attached to their foreheads and slung on the back.

Our guide this morning was with the Mount Everest expedition, as an interpreter. I rode one of the ponies that went on the expedition, a sure-footed little white pony. It’s lucky I saw the mountains this morning, as now at 1 p.m. they are obscured by cloud. One may be days here without it being so clear as today.

This hotel reminds me of the one where we stayed in Granada – big hotel with few in it. The season is the summer, when the Calcutta people come to escape the heat. The rickshaw is the conveyance, pushed by four Chinese-looking men. They have an arrangement for carrying too. Five American women were carried to Tiger Hill this morning. The town is built on the hillside and very up and downy, but the roads are well-built, though no motor (shade of the Daimler) may go more than five miles per hour. The tea-gardens are really extraordinary, terraced on the sides of the hills. It must be very laborious cultivating them, as they have to be carefully weeded between the little bushes.

Now, a happy new year to you, my darling. How I wish I were with you! Give my love and best wishes to the children, and always believe me, my sweetheart, your loving hubby,

George.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.27. George Lambert at 35 Judges Court Road, Calcutta, to his 16-year old son George in England, 6 January 1926

My dear boy George,

How pleased I am to have a Son who writes to me. Your letters have been the only link from home.

I am no longer among the snows. I left them at Darjeeling where good tea comes from, and, tho’ winter, it is very hot here. Apparently a panther came to pay the town a visit and a police officer shot him. My camera is a bit of a nuisance [George was a keen photographer, and had possibly forgot to take his camera]. I should want to take hundreds of photos, everything is so new and so strange. I shall have lots to tell you about. The travelling is tiring. I have slept ever so many nights in the train. I have an Indian servant who makes up my bed which I take with me in a great hold-all – a quilt thing for lying on, two blankets and pillows. Then he looks after the luggage – such a lot; assists me if you please in putting on my clothes; laces up my shoes; fills my tobacco pouch; robs me I know when he buys things.

The dust is very bad too, tho’ there was a shower last night. Generally, it does not rain for two or three months on end. You sleep with mosquito curtains. Monday night I left the carriage window open for air and the brutes got at me in the night. The Hindoo religion is curious: they worship a circular shrine and put up bamboo poles tied with slips of paper which are prayers. Then some won’t kill any living thing, not even a flea.

Well, I hope you are enjoying yourself and are having a happy time in Suisse. You will be going back to school by the time you get this. I should love to see you just now.

My best love, my boy,

Daddy.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.28. George Lambert at Government House, Lucknow, to his wife in England, 8 January 1926

My darling,

I had a piece of luck today. When I got to Benares, the Governor, Sir William Marris¹, was there showing his son around, so he took me in hand too. Apparently the mother died when the son (now about 20) was born. The lad is at Trinity, Oxford and is the apple of the father’s eye. However, it was good for me. I lunched with the Maharahah of Benares. His palace on the Ganges was en fête for the Governor – four elephants gaily caparisoned. I wish I had time to ride one.

The palace is on the river, so after lunch there was a launch that took us up the river where we saw the sacred city and its ghats – places where pilgrims come down to bathe. … The faithful that die near Benares are saved. By the riverside are stacks of wood where Hindoo bodies are burned – we saw one smoking. Then the ashes are scattered in the sacred river. There is a small pool – very sacred – the water is reached by steps; the pilgrims dry the pool by dipping their bodies in it – i.e the wet on the body takes a little water and so many dip in that the pool runs dry. They expect 500,000 in some days in June. It is all so novel and so strange.

There is a golden temple – very sacred – none but Hindoos allowed in, approached from the river by a street about 5 ft. wide, usually infested by lepers and beggars cadging from the pilgrims, but the police had cleared a way for His Excellency, so there was no eyesore. You can’t compare English with Indian habits of life. Why a plague does not break out regularly in a place like Benares, I can’t conceive – the people live so thickly together.

Then we saw Sarnath – which was a vast monastery and Buddha started his preaching there. But when the Mahommedans conquered it, they compelled the Hindoos to desecrate their own sacred shrine and first demolish and then bury it. We saw that in Sicily – one religion is conquered and compelled to be slaves. Then, at 10 p.m., after dining at the Maharajah’s rest house, I came on the Government special train. Two nights following each other in the train is too much, so I am tired. One thing – I seem to have brought luck in the shape of rain – we arrived at 8 a.m. and it has thundered and lightened and rained up to now (12.30), so I’m indoors writing this. I have a suite about as long as four houses wide in Grosvenor Road [their house in London], but there – I’m the only visitor. …

I have a wire from the Military Secretary: return to Viceroy. It looks as if I shall be well looked after on the road – after Delhi to Peshawar, Khyber Pass, then back to Delhi and gradually down to Jaipur, Udaipur, on to Ranjit’s, thence to Bombay and then home. I wish I were going there now; but really one gets used to lots of things. I seem to have been away months and to have a difficulty in imagining there is such a place as London or Spreyton. It really is a tremendous experience, but I shall not be sorry when it’s over. By the way, I forgot we were welcomed yesterday by the Rajah with a golden kind of festoon placed over the neck, reaching down to waistcoat level and by others with necklets of flowers – marigolds and the like. I had three lots on at once at one time – i.e. garlands of flowers.

9th January.

I went for a ride with the Governor and his A.D.C. this morning, then went to the old residency which was such a historic place in the Mutiny. You have to see the place to imagine it. 3,000 souls cramped up; less than 1,000 came out alive. Then afterwards I actually played a game of golf. I used another man’s clubs and just beat my opponent by one hole. Thus ended that day, but it gets cold at night – indeed, the climate now is perfectly delightful. We breakfasted in a tent overlooking a beautiful garden – quite cool; indeed I have my sweater over my grey flannel suit.

You have heard your mother speak of Hodson² of Hodson’s Horse. I remember her talking of it. Well, he died in this house and the Governor last night said a lady declared having met him on the stairs. However, I slept well.

10 January – Sunday.

... I played a round of golf with the Governor this afternoon with borrowed clubs and just got home by one hole. This evening, I have been to church – the worst sermon I have heard for a long time. There were a lot of Anglo-Indian boys – white fathers, black mothers – very sad, as they were looked down on by both.

Now, old darling, I shall hope to get some news of you at Delhi. Fancy, you won’t get this until about 1 February.

With all my fondest love,

George.

¹ Sir William Marris (1873-1945) joined the Indian Civil Service in 1895, passing out first in the notoriously difficult exam. He was Governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh 1922-1928.

² Major William Hodson raised a cavalry regiment in the British Indian Army at the time of the Indian mutiny of 1857. The Regiment’s original name was Hodson’s Horse. It subsequently changed its name several times and still exists in the present Indian Army as an armoured regiment.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter 2.29. George Lambert at the Palace, Jamnagar, Kathiawar (home of Ranjit Singhji, the Maharaja of Nawanagar), to his wife in England, 16 February 1926

My darling,

Sometimes I get nervous that I haven’t heard from you. I wonder what can have happened. Anyhow, I shall know soon, as in 11 days the Rajputana sails.

Ranji¹ has just come here. He has been ill and not fit to travel. However, I have got on very well. They are very hospitable. When he was not here, we had about eight to dinner; when he was here there are about twenty-four – his relatives have to pay their respects to him.

My day today began at 7.15 – tea, toast and bananas. Then into riding breeches and on a horse from 7.45 to 9.30. Then shave, bath and writing this. The bearer or servant does everything – button my gaiters, even helps with my braces, laces up my shoes and is quite annoyed if I attempt to do anything myself. In the mornings the air is lovely – bright sunshine and not too hot. This place is near the sea, so there is often a breeze until the afternoon, about two to four, when it is hot.

The other morning I was taken out in a Ford car. The country is level and dry and no fences. They saw a herd of black buck – really deer – so the car was driven round them until a fine buck stood broadside and gave me a chance with a rifle. It was about as far as the post-box from our house. I aimed sitting in the car and across the driver and was fortunate to get the beast exactly right. So my stock is high. It was mostly luck, though!

17 February.

Last night the Gaekwar [Maharaja] of Baroda [a larger and richer princely state] was given a banquet here, at 8 p.m. It was in a separate banqueting hall; gold or rather silver-gilt plate; all sorts of coloured lights; ‘God save the King’ in electric globes at the entrance. The beautiful evening – the evenings are always beautiful – made it a sort of fairyland. As it was Baroda’s first visit, there were brought to him trays of rupees, sweetmeats and silks as presents. They really have some pretty customs.

There is a motley collection at a new palace begun but not finished – pictures, plate, furniture – some very fine, some very common. In one room were hung 10 cuckoo clocks like the one I bought the girls in Switzerland. …

Good-bye, my darling; this is I hope my last letter as I shall sail by the mail after. Give my love to the children and your dear self too.

Your loving

George.