TALES OF THE STAVERS CAPTAINS PART 1: THE NORTHUMBERLAND STAVERS

1.4. George Stavers (1788-1832) and his sons Captain John (1822-1902) and Captain George Stavers (1825-1891).

George Stavers the elder appears in the crew list of the whaler Perseverance (of which his uncle William was earlier master) as an apprentice in 18041, but I have found no further record of him as a seaman and he presumably did not take to life at sea. Instead he seems to have taken over the family farm of North Moor in Woodhorn. A letter from one of his grandsons states that on his death the farm was sold and the proceeds were distributed to his children. However, it is clear from the records that he was a tenant farmer, although no doubt on some sort of long term lease as the farm was in the possession of two generations of the Stavers family (according to Land Tax records, the freeholder was the Reverend Robert Darley). George’s widow stayed on at the farm for a couple of years after his death, after which the farm was put up for rent and no doubt at that point the livestock and farm machinery were sold. He was 44 when he died and is buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s, East Hartford, Northumberland and his gravestone survives.

George married a local girl, Mary Watson, and they had two sons, both of whom became notable merchant navy captains and eventually owners of their own ships, employing other captains to command them. They were based on Tyneside and, unlike other members of the family, they never went in for whaling. The export of coal from Newcastle and other Tyneside ports was a major part of their business. English coal, which was mainly exported from Newcastle, was sought far and wide and was exported as far as the Antipodes. As a Melbourne newspaper put it in 1855: “for coals that can be used either for a small or a large fire; that possess heat and strength enough for smith’s work, and yet will give a sparkling liveliness to a drawing-room, nothing can surpass those from England”.2 On the return journey they would ship a huge variety of different goods, from sugar to wheat or guano.

Captain John Stavers (1822-1902)

John Stavers began his maritime career in traditional style as an apprentice (probably as a cabin boy) in 1837 at the age of 15.3 A cabin boy was the lowest of the low and was given all the most menial tasks. Captain T.R. Stavers (who had been to school before being sent to sea by his father) recalled that when he became a cabin boy “little did I think I should have to wash Plates end clean Knives. I thought my Father, being Master of a Ship, and myself, brought up at Boarding school, that I should be exempt from such menial service”. John quickly worked his way up and obtained his master’s certificate in 1851, “having served 14 years as apprentice mate master in coasting and foreign trades”.4

Enterprising captains had opportunities to make money other than what they were paid by the owners of their ships. Often they negotiated a share of the cargo for themselves, and also took opportunities while at sea to buy and sell cargoes. It was not uncommon for successful captains to take shares in ships and if they were clever to end up as shipowners. In his memoir, Walter Runciman (also from Tyneside), later Lord Runciman, describes how he worked his way up from being a 14-year-old cabin boy to becoming one of the largest shipowners in the country. So it was with John and George Stavers, albeit in a much smaller way. Like Runciman, the brothers probably started by taking shares in vessels. John was captain of the Northumberland, owned by Marshall & Co from 1863 from 1867. By 1867 he had obviously taken a share in the ship as the owners were listed as Marshall and Stavers; and thereafter the Stavers appear as the sole owners, employing someone else (Captain Peter Heslop) as captain. The brothers founded a company called Stavers & Co and between them, the brothers commissioned a number of ships either jointly or separately.5 They became one of the best-known owners on Tyneside, where the family were already well-known because of the earlier exploits of their cousins in the whaling industry.6

Walter Runciman was a very young able seaman on the Northumberland on a journey carrying coal to Alexandria. In his memoir, he wrote that

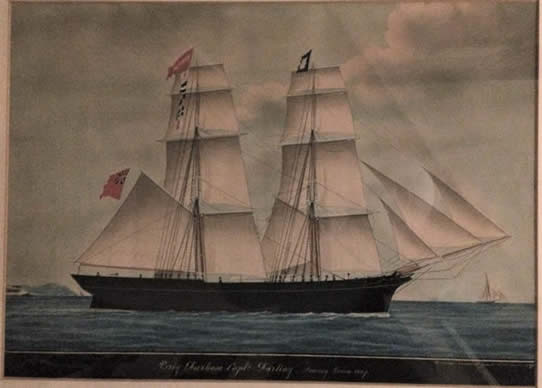

In 1866 the Stavers brothers took delivery of a new collier vessel, the Durham from Seaham shipyard. They were obviously very proud of her, as they had her portrait painted in Genoa in 18678, a painting that remains in the hands of George Stavers’ descendants. John Stavers took command of her on what was probably her maiden voyage, thereafter handing her over to Captain John Darling, a captain much employed by the Stavers. In seafaring, hazards abound and one is the spontaneous combustion of certain cargoes. Only two years after her launch, when she was carrying a cargo of coal to the Mediterranean, her cargo spontaneously combusted. Walter Runciman was in one of the vessels (the Isabella) that went to her aid and graphically describes it:

Walter Runciman managed to save the ship’s chronometer (an essential tool for navigation in those days). He returned to the Stavers and it remains in the possession of the author.

The Brig Durham, Captain Darling, leaving Genoa in 1867 By Domenico Gaverrone

John seems only to have commanded sailing vessels, even though steam-powered ships were becoming common during his career. The Durham seems to be the last ship which John commanded and his name largely disappears from the records after that, except as an owner. He owned the Ann Mills, a sailing vessel trading with the eastern Mediterranean which came to grief in 1875 in gales in the Bay of Biscay while taking a cargo of grain from Acre to Plymouth; and also the Norham, a steamship trading with South America, which he seems to have disposed of only around 1880.

John lived all his long life at Cowpen near Blyth. He married Elizabeth Hogg but does not appear to have had any children. There is a tale in the family of George Stavers that John’s wife Elizabeth was a master mariner in her own right and would wear a brimless top hat (captains when on shore would dress up in smart three-piece suits and hats to match). I have not found any independent record of this. John lived to the age of 80 and his grave and that of his wife is in Horton, the parish of the family farm of North Moor where he was brought up. His life is well summed up in an article in this article in the Shields Daily News of 13 June 1902:

Captain George Stavers (1825-1891)

George Stavers seems to have been the more dynamic and entrepreneurial of the brothers. He made the transition from sail to steam and he is usually the brother mentioned in connection with ships commissioned by Stavers and Co.

George followed his brother to sea at an early age. He is listed as a merchant seaman in 1841, at the age of 20, and passed the examination to become a captain in 1850 when only 25.11 The first ship he commanded was the Darien, a sailing ship trading between Blyth and Rio de Janiero. The South American coast was notoriously unhealthy. In 1853, George wrote to the owner of the Darien from Rio that seven crew had fallen victim to a fever that was raging on that coast, and that he had been ill as well but was now convalescent.12 The Darien on that occasion was picking up a load of sugar to take to the Mediterranean, and that was probably her usual cargo on the return voyage, with coal being the outward cargo.

From 1855-56 and again in 1858-59 he was in command of the Black Prince, with which, in the words of Walter Runciman, he “distinguished himself in many ways during the Russian [Crimean] war of 1854”.13 The ship was chartered to the Government. In 1855, she is recorded as arriving at Malta from Balaklava with 81 Spanish muleteers; and in 1856 she is recorded at Woolwich loading forage wagons and other goods for the troops in Crimea and later, fter the war had ended, arriving at Spithead from Malta and the Black Sea bringing back ordnance and stores.14

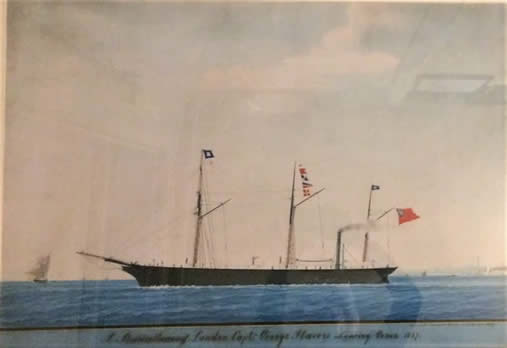

In 1857 he was captain of the Jarrow, a steamship which traded between London and various ports in Italy. The Genoese ship artist painted a picture of the Jarrow as she was leaving Genoa in 1857, a painting that is still in the possession of George’s descendants.

The Jarrow, Captain George Stavers, leaving Genoa in 1857 By Domenico Gaverrone

He seems subsequently to have commanded a variety of vessels, including the Scotia taking coal to Malta in 186015; and two Greek-owned ships, between 1859 and 1861, the Marco Bozzaris and the Palikari, trading between London and the eastern Mediterranean. In early 1862, he was recorded as captain of the Rangoon, a vessel built specifically to transport portions of the Rangoon to Singapore telegraph cable.16 In 1862, he took command of the Cairo, a brand new fast Italian-owned vessel to take mails from the Italian coast to Alexandria. This was a period when there was an increasing demand for passenger travel, and instead of passengers being incidental to cargo, they began to have ships specifically designed to cater for their needs. The port of Alexandria was particularly important as before the Suez Canal was built the quickest way for passengers to get to India and beyond was to go from Europe to Alexandria by boat, and then to travel by rail to Suez (via Cairo) and take another boat to India. The Cairo was accordingly designed to attract passengers. A press report described her accommodation:

George seems to have made a bit of a speciality of taking on new passenger vessels, as in 1864 he is reported as being the commander of a just launched new steamer called the Thames, taking passengers to Quebec and Montreal.18 He does not seem however, that he did more than take these vessels on their maiden voyages, as he is not shown as their captain on any available Lloyds List. There are several mentions of ships with a captain named Stavers in the 1860s, but none can be definitively linked to George.19 It seems that he probably stopped going to sea in the mid-1860s, perhaps because he was now rich enough to concentrate on commissioning new ships for Stavers & Co; and perhaps because in 1866, at the age of 41, he married a young wife, the 20-year old Sophia Jane Curson Mackey.20 They lived in Morpeth, and increasingly during the 1870s he is mentioned in the local press in connection with civic activities in Morpeth, apparently having become a pillar of Morpeth Society. He also joined the local Freemasons’ lodge.

Two years after his marriage, he took delivery of a new sailing ship, which he named the Sophia Jane after his wife and which she launched.21 The vessel had a number of different captains over the years. She travelled regularly between Tyneside and ports in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea during her first four years, probably carrying out coal and returning with other cargoes – wheat, maize and linseed are mentioned in the records. She then switched to roaming more widely, making a couple of trips to the West Indies as well as regular journeys to the Baltic and to Lison and Madeira. In 1870 she sailed to Bahia in Brazil, returning with a cargo of tobacco destined for Hamburg. In the English Channel, however, she caught fire and was destroyed (all her crew were rescued). There was an official Inquiry into the cause, which was that the tobacco had spontaneously combusted – making this the second Stavers vessel to be lost through spontaneous combustion of her cargo.

The longest lasting and probably most successful vessel belonging to the Stavers was the Stavers, a large and handsome sailing ship of which the family have a painting (see home page). She was commissioned by George Stavers for the China trade, and was launched in 1869, tasking her first cargo of coal to China shortly after, returning with rice. She remained in the ownership of George Stavers until 1879, when she was sold and renamed. She regularly made long distance journeys, mainly to Rangoon and Singapore, but also to ports in India and what is now Indonesia.She also made joureys to the Americas and Australia (in 1878 she put in to St Helena when she sprang a leak while carrying guano from the Lacapedes Islands off Australia). She was a real workhorse of the sea and the the longest lived of the Stavers' ships, continuing to sail for another 14 years under her new owners, Croatian brothers who renamed her Dussan (she was scrapped in 1873 after being damaged).

George Stavers had an interest in the construction and operation of vessels and seems to have qualified as a marine surveyor, as he so described himself at the baptism of his son John in 1882 and appeared in that capacity in a court case in 1880.22 He also developed a sideline as an inventor, patenting a "fish fin rudder" for steering vessels whose main rudder was disabled, for which he won medals at marine exhibitions, although it is not clear whether he had any commercial success with it.23

According to tales told by his descendants, George (like his uncle Japan Jack) was immensely strong and could write with a weight attached to his wrist. Both George and John sold their remaining ships in about 1880 and George and his family moved from Morpeth to Enfield, and from that time on they were London-based. According to family stories George met his wife in London and seems to have stayed here quite often, as many of his ships, while based on Tyneside, spent time in London (at the time of the 1861 census was lodging in Stepney), so it was a familiar place.

George Stavers and his wife Sophia Jane had seven children, three girls and four sons. It seems that by the time of the move to London George regarded himself more as a gentleman and ship-owner than a master mariner (the probate record after his death describes him as “gentleman”) and saw the future for his children as being in a higher social sphere than the merchant marine. The exception was the eldest son, George Stavers (1876-1891). As a boy he had inherited his father’s strength and was known as a champion wrestler who used to beat all the pit boys from the mines near Morpeth.24 When still a teenager he contracted a throat infection and was sent to sea for his health, as a 16-year-old apprentice on the Maiden City. He perished on his first voyage when he was swept overboard near Capetown by a giant wave. The other sons and daughters all became assimilated with or married into the London professional classes.

NOTES (1) https://whalinghistory.org (2) The Age (Melbourne), 4.6.1855. (3) List of apprentices (4) National Archives BT 112/67 and Mercantile Navy List 1850. (5) The records refer sometimes to Stavers & Co and sometimes to John or George Stavers as the owner; it seems likely, however, that most of their ships were owned by the company, even though one or other brother had the main interest.. (6) Letter of 8.9.1943 from George’s son John Stavers to his sister Barbara Lambert (7) Walter Runciman Before the Mast and After, 1924, p. 138. The book gives a good description of the journey and life aboard. The Northumberland under Heslop appears to have been a happy ship, and 50 years later the Runciman company launched a steamer of 7,500 tons with the same name from the same spot (the Northumberland was 550 tons). (8) Domenico Gavarrone (1821-1874). There is a museum outside Genoa dedicated to his work. (9) Runciman 1924, op.cit. (10) Newcastle Journal 28.5.68. (11) National Archives BT 112/67 Mercantile Navy List 1850. (12) Shipping and Mercantile Gazette 16.6.1853 (13) Walter Runciman: Collier Brigs and their Sailors, 1926. Runciman refers to John Stavers, but it is clear that this is a mistake for George. There are certificates in the possession of George’s descendants recording that the Black Prince, master George Stavers, was “in Her Majesty’s service employed upon, and complete, according to Charter, in men and stores” (14) The Times 15.2.1856 (15) Ibid 27.11.1860 (16) Survey reports, Lloyds Heritage Foundation; www.searlecanada.org. George’s son John, in a letter of 8.9.1943 to his sister Barbara Lambert, claims that he was also involved in laying cables to Greece and Turkey. (17) Newcastle Courant, 3.10.1862. (18) Cambridge Independent Press, 11.6.1864. (19) Possible ships include the Mary Ann (1854-55); Albatross (1859); Rival (1861-2); and May Queen (1864). (20) Her father was a draper from a Northumberland family and her mother came from rural Devon. (21) Morpeth Herald, 21.11.1868 (22)The Times 22.9.1880. He is also described in the Times of 23.7.1886 as “surveyor to the Registre Maritime) (23) No. 1488, London Gazette of 12.5.1776. Ses also Newcastle Courant 8.9.1872. His family have three large and enormously ornate certificates for the medals he won. (24) Family story.

|