THE THREE LADIES’ TRIP TO SOME SILK ROAD TOWNS IN CHINA

Being the account by Sophia Lambert of a three week journey that she made with two other retired senior civil servants, Jenny Bacon and Kathryn Morton, in May-June 2006.

We stayed mainly in 3-star hotels and used a travel agent in the UK to book and prepay the hotels (partly to avoid having to carry large amounts of cash, as we had been told that changing money in the remoter areas could be problematic). The agent also booked the overnight train journeys for us, although the bookings did not always work smoothly. Otherwise we mainly organised our own travel as we went along. In towns we walked everywhere except on a few occasions when we took local buses or hired bicycles. For trips outside towns, we mainly hired a car with driver for the day, so that we could spend as much time as we liked in the places we were visiting. We used guides only on a very few occasions. What follows says relatively little about the tourist sites, as these are well described in the guide-books. Photos courtesy of Jenny Bacon.

London-Beijing-Xi’an 12-13 May At the airport, the check-in staff are amazed at our lack of luggage – Jenny and Kathryn have ruck-sacks and I have my suitcase on a stalk that is barely more than hand baggage size. An uneventful 10-hour journey by Air China to Beijing, which introduced us to our first taste of Chinese breakfast – a stuffed dumpling in a sort of ultra-tasteless rice slurry, the so-called congee or zhou. Then after a quick lunch of Japanese noodles in Beijing airport, a two hour flight on to Xi’an, which is some 600 miles south-west of Beijing.

Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, 13-16 May I don’t think any of us knew what to expect, but Xi’an (Sian) turned out to be a vast city – some 7 million people. We drove in from the airport through apparently endless suburbs to a centre that rivalled any major Western city in its array of glittering modern sky-scrapers. The main difference from a modern Western European city was the appalling pollution. A chokingly heavy haze hung over the entire city, with a number of tall factory chimneys belching out yet more black smoke – the sort of chimneys that in Western Europe would be sited some way from the city centre. The main drag, with its fashion and electronic gadget shops, could well have been in Japan, not least because it was tremendously clean – not a piece of litter to be seen. Even in the old Muslim quarter, which has not been modernised and had the usual broken paving stones and potholes, there was much less rubbish than one would expect in that sort of environment. On the telephone to John, I said that it was three-quarters Japan and one-quarter India.

Everywhere, new and even shinier sky-scrapers and grand shops were going up; it was if the undeveloped parts of the city were morphing into modernity before our very eyes. I remember being told recently that the building activity in the Gulf was such that half of all the world’s cranes were there, and reflected that surely the other half must be in China. Then I realised that there was hardly a crane to be seen; everything, it seems, is carried up and down by hand by the immense labour force. Even though the city was full of people, however, one had none of the impression of an almost insupportable press of humanity that one gets in India.

Our first day was a Sunday, when traffic was light. But by Monday Xi’an was as busy with cars as any European city. The streets are immensely broad and full of all sorts of traffic observing few noticeable rules. Lane discipline is clearly not a concept that figures in the Chinese driving test. Even on the motorways outside the town, little old slow vehicles thought nothing of trundling gently along in the fast lane, and cars passed on whatever side was convenient. In the city, crossing the road was terrifying; a game of chicken with pedestrians and vehicles weaving around each other, the former often finding themselves marooned on the middle of the road with two opposing streams of traffic passing within inches on either side. There were zebra crossings, but they seemed merely to give pedestrians equality with wheeled traffic. As we travelled towards the less prosperous West, crossing the road became easier, but only because there was less traffic; the anarchy was the same.

Xi’an is on a large and very flat plain and was the start of the silk route, having become the capital of China over 2,200 years ago and remaining so for almost 1000 years. The Tang dynasty laid out the city in its present strict grid pattern (a pattern we found reproduced in almost every city we visited). But little remains of the old city except for the magnificent (albeit much restored) 16th century brick walls round the central rectangle of the city. They must total some 15 km in length and are immensely thick, with battlements and huge gateways, and a road along the top wide enough to take several rows of vehicles – although today only pedestrians and cyclists have access (bicycles were for hire).

On top of the Xi’an city walls

Xi’an city walls seen from below

Also as in other cities we visited, in the middle of the central cross-roads of the central rectangle of the town there was a 16th century “Bell-Tower”, and near it a “Drum-Tower” (the drums were sounded at dawn; the bells at sunset). But the only ancient monument that really grabbed us by the heart-strings was the Great Mosque, the largest in China. One enters a small door-way to find oneself in a complex of courtyards and gardens with a few old Muslims sitting around on ledges and steps. It was an extraordinary transition from the heat, dust and never-ending noise of the streets outside into a haven of greenery and calm. Between the courtyards there are elaborate Chinese style gateways of the sort normally associated with Buddhist temples, and the Mosque itself has a temple-style tiled roof with winged eaves. But everywhere there are small Muslim touches; arabesques and Arab calligraphy. The Mosque was established in the mid-8th century, but has been rebuilt and much restored since then, so the buildings are probably not that old. But they were of a seductive and timeless charm, and one of the most attractive sights we saw on the entire trip.

Inside the mosque complex at Xi’an

The mosque at Xi’an: detail with Arabic script

Old men outside the mosque at Xi’

Our hotel is 3-star standard international, with a good sprinkling of Western visitors. We have two double rooms between us (singles don’t seem to exist) and Jenny has worked out a complicated rota to ensure that each of us has the same number of days with her own room. We eat at the hotel a couple of times, but otherwise try small restaurants in the town, with mixed success. The main problem is that except in big tourist places the menus are all in Chinese and none of the staff speak English. I quickly become adept at circling round other tables to see what other customers are eating, and pointing out to the waitress dishes that look good. The people at the other tables, once they realise what I am doing, are friendly, and sometimes there is somebody with some English who helps. But mostly I am reduced to making baa-baa and moo-moo noises to discover if meat is lamb or beef, to the amusement of all. We do get an excellent Canton Duck for my birthday at the Xi’an Roast Duck Restaurant. But most of the time – both in Xi’an and elsewhere on our trip – I feel thoroughly frustrated, suspecting that if only we could read the menus all sorts of gastronomic delights would become available to us.

Life is complicated by the fact that Jenny is a big meat-eater and likes spicy food, while Kathryn does not tolerate more than a tiny amount of chilli. This becomes more of a problem as we go West, as the food gets steadily hotter. Kathryn finds a phrase in her phrase-book asking for only a little bit of chilli, but it does not always work, especially in Xinjiang, where not many people read Chinese – although we do get somebody to write down the equivalent phrase in Uigur and that helps. On one disastrous occasion we ended up with double the normal amount of chilli – great piles of whole chilis in our Uigur noodles. One odd thing is the apparent total absence of sweet things. In Japan, even though restaurants do not serve dessert, there are usually lots of shops selling bean-curd sweets to which one can retire to satisfy one’s sweet tooth after a meal, but here there is nothing. There are occasional biscuit shops (also displaying huge and sickly-looking western-style wedding cakes), but the biscuits that we try are dry, boring and only just sweet. Strange to find a society apparently so completely without a sweet tooth. *************************** The terracotta warriors and the imperial tombs Xi’an is the jumping-off place for visiting these, and we book ourselves on two tours organised by an agent in our hotel chiefly for Chinese tourists. We set off the first day in a minibus to see the imperial tombs and various other sights, including the site of the “Xi’an incident” in 1936 when Chang Kai-Shek, who was far more interested in trying to eliminate the communists than in stopping the Japanese invasion, was arrested by one of his own generals and forced to sign an agreement with the communists that he would join them in fighting the Japanese. The whole place has been turned into a sort of theme park celebrating the incident, including a live Chang Kai-Shek look-alike dressed in full uniform next to whom the tourists can have themselves photographed. The imperial tombs are mainly unvisitable mounds, but we are able to climb down to one burial chamber deep underground, that of a 7th century princess. It had well preserved frescoes, including some particularly beautiful ones of elegant 7th century court ladies.

Theme park at Xi’an

One of the many extraordinary sculptures that litter Chinese parks

Another sight on the tour was a big Buddhist monastery. Our group is shown round by a monk. At the end of the visit he ushers us into a room, makes us sit on the ground and harangues us incomprehensibly. He goes on, and on, and on. Judging by the amount of surreptitious changing of position, our urbanised Chinese fellow tourists are just as unused as we are to sitting on their haunches for long periods. At one point the monk addresses a question to one of the Chinese tourists. He obviously does not answer satisfactorily, as he is sent to sit at the back. We eye each other and have serious problems, again shared by our Chinese companions, in avoiding the giggles. Afterwards we ask the unfortunate man what he had said wrong, and he laughed and said he was not sure but the monk seemed to think he was not religious enough. Finally, at the end of the harangue, the monk prepares to sprinkle us with some sort of Buddhist holy water. I am at the end of the front row, and am his first target. He fixes me with a basilisk stare, addresses me with what sounds like a firm condemnation of foreign devils, and flicks a spray of water in my direction. The Chinese giggle sympathetically.

Generally, we find that there are very few Western tourists, even at the big sites, but huge numbers of Chinese ones – with increasing affluence, domestic tourism seems to be increasing exponentially. There are also quite a few groups of Japanese and Koreans. All the sites have high entry fees and are organised down to the nth degree – no doubt a legacy from Maoist times. At the bigger ones, some sort of theme park has usually been built on the way in, and on the way out everybody is forced to go through a huge commercial area full of stalls with tacky souvenirs – the Chinese have nothing to learn from the National Trust in this respect. Even in the tiniest and most isolated sites, somebody turns out to sell one a ticket and at the end unlocks a small “shop” full of dusty display cases containing the local tourist tat. Round Xi’an there are also huge outlets (at which the tourist minibuses all stop for a full 20 minutes) selling the more expensive sort of souvenir – endless jade necklaces and bangles, huge and horrible sculptures in jade and stone of dragons and other beasts, and enormous porcelain vases, standing many feet high – everything that the most vulgar nouveau riche Chinese could possibly desire to decorate his new residence. Unfortunately, there is none of the innate sense of design that one finds everywhere in Japan.

The second day, we go on the minibus tour that takes in the terracotta warriors, and there is no doubt that this is one of the wonders of the world and of the highlights of our trip. On both our trips, the guide with the minibus speaks Chinese only, and at the terracotta warriors he tries to foist an English-speaking guide on us. Thankfully, we manage to resist (one problem is that their English accents are mostly so appalling that it is an effort just to listen to them), and wander round at will. The warriors are in trenches, thousands and thousands of them marching four abreast, with many yet still to be uncovered. There are also figures of generals, including one marvellously haughty top general, and horsemen, horses and chariots. Although one has seen the small groups of warriors that the Chinese have lent to the West for exhibitions, this does not prepare one for the amazing sight of the terracotta army en masse. The trenches in which they and their horses stand were originally covered in mud roofs. As these collapsed, many of the figures were smashed into smaller or bigger pieces. As one walks past the jumble of body parts in these sections and then comes to a section where the figures have survived intact, it is uncannily as if the broken pieces are picking themselves up before one’s eyes and becoming whole again, as in one of those cartoon movies where the smashed up hero is miraculously restored to his original shape.

Terracotta Warriors at Xi’an

A haughty terracotta general at Xi’an

For once, on this trip there was another Westerner, an immensely tall Dutchman – bearing out the statistic that the Dutch are now on average the world’s tallest nation. He told us that he was an exporter of Chinese goods to Europe, acting as a middle man and dividing his time between China, where he had a Chinese-speaking partner, and the Netherlands. He confirmed the extraordinary capacity of the Chinese labour-force to produce goods to whatever high quality specification that they were given, but complained that they were thrown by any problem which required initiative and judgement, contrasting them in this respect with the Indians, who always produced half a dozen imaginative – if not always desirable – ideas for doing things differently. Of course lack of innovatory capacity was also a charge that used to be levelled at the Japanese, and that phase did not last long.

**********************

Lanzhou, Gansu Province, 17-18 May We take the overnight train to Lanzhou (Lanchow), travelling by “soft sleeper”, the most luxurious class, used according to the Rough Guide only by foreigners, party officials and rich entrepreneurs. To add to the luxury, we have booked a four-berth compartment all to ourselves. The berths are not bad, a bit hard but with pillow, towel and duvet. There is boiled water in a flask and an attendant to every carriage. Soft sleeper carriages also have a choice of Western-style or squatting toilet, and there is washroom with a row of basins in which everybody cleans their teeth etc. China is full of notices in fantastical fractured English, and some of the best of these are in train toilets. On the outside of the door it says “No occupying while stabling”. Inside, one is enjoined to “Please develop drainage”.

About half an hour before arrival at one’s destination the attendant wakes one up to give one back one’s ticket (which is confiscated in exchange for a plastic token at the beginning of the journey), providing a comforting reassurance that one will not miss one’s stop. The trains trundle along at a dignified 50 mph or so. Getting on the train is slightly alarming at first. To get into the station one has to join a long queue for X-ray machines. Everybody then remains corralled in the waiting-room until the train is ready; then a gate opens and there is a mass stampede onto the platform. But we quickly discover that reserved places really are reserved and that our places will be waiting even if we get left behind in the stampede.

A thousand years ago, Gansu Province used to be considered the outer limit of China and it did not become a province until the 13th century. Now, although it has some Muslim minorities, it is very much part of the Chinese heartland. But as one moves west, the land becomes increasingly drier, wilder and less prosperous.

Lanzhou on the Yellow River

Lanzhou is where the silk route crossed the Yellow River (actually muddy brown at this time of year). It is an elongated town strung out over some 30 kilometres along the narrow river valley. The valley creates a wind tunnel which thankfully lessens the pollution, at least near the river. The river banks have been attractively laid out with greenery and rather good modern sculpture, and are full of Chinese strollers. Locals offer trips on the river in what was presumably the traditional river craft – planks lashed to blown-up pigskins which serve as floats. There is also a cable-car up to an attractive Buddhist temple on the opposite bank, where we spend a lazy afternoon. The temple is surrounded by gardens and cafes and we are introduced to “Muslim tea”. This comes ready-packaged in plastic cups, full of nameless but interesting-looking dried fruit and leaves, together with two large chunks of crystallised sugar. Boiling water is poured over this mix, usually with aplomb from afar out of a long-spouted kettle. It has to be left to steep for about quarter of an hour, but then produces a most pleasantly sweet and aromatic drink – the only sweet thing we are offered in China. Our impression is that it is a folk-drink now drunk mainly by the Han Chinese, as it is less and less available as we go west into the truly Muslim areas.

Lanzhou: rafts with inflated pigskin floats

Pagoda in Lanzhou – a good place for Muslim tea

The rest of what we see of Lanzhou is pretty unexciting. I do manage, however, to get myself some stylish new glasses for £20. I had brought my prescription with me for the purpose, and walked into a glasses shop while Jenny and Kathryn are in a photograph shop trying to do something technical with Jenny’s digital camera. The glasses are made while I wait. There is a man with a small pet dog sitting in the shop for a chat. The Rough Guide includes the word for “dog” among the food terms in its glossary, so I point to the dog and proudly say “gorou”. My audience looks somewhat aghast, but then giggles. I am given to understand that I have said the word for dogmeat or the sort of dog one eats. When a dog is a pet, it is apparently a “pikha”.

We also walk through the streets that constitute the food market near our hotel and buy the most delicious lychees and mangoes. The fruit and vegetables are wonderfully varied, with a particularly wide array of unrecognisable greenery. We then get on to the fish and sundries section, which includes live eels, carp and other fish; huge pickled squid; and frogs, snails and terrapins. There are surprisingly few live chickens on view, although judging by the huge number of eggs on sale there is no shortage. We wonder if bird flu has driven the chicken market underground.

Our hotel is of a sort with which we are to become very familiar. Built in more collectivist times, it is huge, with about three separate buildings, apparently each with different classes of accommodation. At least one of these buildings appears to be completely shut and the rest is very empty. As a chargeable day in a Chinese hotel goes from 6 am on day of arrival to 12 pm on the following day, a high vacancy rate seems to be taken as the norm. The lobbies are huge and lugubrious, although usually with a smart souvenir shop in the grander ones. Vast and hideous sofas and armchairs with apparently soft and squishy cushions seem to invite one to sink into their depths, but are as hard as if they were carved in wood; they are also covered in uncomfortably tacky plastic leather. The rooms conform to international 3-star standards, with two large beds apiece; two chairs; a desk; standard lamps dotted around; a huge TV (with about 20 Chinese channels); thick pile carpet; an en-suite bath or shower; the usual row of little packages and tubes of soap, shampoo etc. But somehow many things are subtly wrong. The bath only fits a midget. The towel rail is behind the door and not reachable from either basin or bath. There is no top light in the bedroom, and none of the other lights is quite bright enough to lift the prevailing gloom. It is clear, moreover, that many of the fittings in all the hotels have been centrally ordered; there is for instance an identical console of light switches by the bed in almost all the hotels we stay in (the same applies to some street decorations; there is one that looks like a giant metal allium flower that we see in several cities).

West of Xi’an, few hotel staff speak any English, and often the name of the hotel itself is in Chinese only. Making oneself understood is a major exercise, not least because all three of us each think that we can explain things better than the others, so the unfortunate staff are faced with the three of us trying our own brand of English for foreigners (in one hotel we were asked which of us was the tour leader; our initial reaction was to say that we did not have one, but then one of us said, quick as a flash, “we all are”, so since then we have been referring to ourselves as the “three tour leaders”).

Lanzhou is also our first experience of Chinese breakfast unadulterated by Western touches. There is a central buffet consisting of a dozen dishes of cooked or pickled vegetables of various kinds, mostly cold, as well as some cold noodles; cold boiled eggs; a choice of plain or stuffed dumplings; and two or three different kinds of soup. These invariably include an aggressively tasteless rice slurry (which seems to come in both white and brown versions), and usually an extremely spicy soup full of noodles. The Chinese do not seem to drink anything at breakfast apart possibly for some fruit juice, and we have to struggle to make the staff understand that we want tea. Because we are Westerners, however, in the more sophisticated hotels we are automatically brought fried eggs, which with luck will be both hot and good – although not the easiest thing to eat with chopsticks.

Lanzhou is also where we are introduced to the hotpot restaurant beloved of most Northern Chinese. The tables are round with a hole in the middle, where there is a gas-ring fuelled by a large blue calor-gas cylinder under the table. A large pot of bubbling aromatic broth is placed on the gas-ring – one can have either spicy or non-spicy broth, or a pot with a division down the middle with spicy on one side and non-spicy on the other. The broth looks to be already full of edibles. But these are no more than flavourings, and one must then order one’s edibles which one plunges in the broth to cook. Anything goes – paper thin slices of raw meat; prawns and other sea-food (very expensive); the full range of vegetables from spinach to sweet potatoes; bean-curd; dumplings; giant noodles. At the end, some of the broth is strained into a bowl to make a rather delicious soup (as in Japan, soup marks the end of the meal in China). The heat of the summer is not the best time to be clustered around a bubbling bowl of hot broth with a gas ring within inches of one’s seat, but it must be an enormously comforting sort of meal in the cold Chinese midwinter.

************************

Bingling Si Caves We came to Lanzhou mainly to see the Bingling Si Buddhist “caves” nearby, mostly dating from the 5th to 9th centuries, among the earliest Buddhist art in China, brought by monks from India travelling East along the silk route. This was the one expedition that we had been persuaded to pre-book from London, so we had an English-speaking guide – a student who claimed that he was not paid, the attractions of the job being the chance to practice English and the chance of a tip; and he duly proceeded to extract a large one from us at the end of our excursion. He did not know a lot about the caves, but he could at least translate the descriptive signs for us, which would otherwise have remained a mystery. He had not a lot to say of interest about life in China, but did complain bitterly of the widespread corruption.

To get to Bingling Si, we had first to drive for about an hour and a half out to a dammed part of the Yellow River, and then to go for an hour by speed-boat along the lake created by the dam – a spectacular trip. The “caves”, up the sheer cliff-side of a river canyon, turned out to be much smaller than expected, some not more than a couple of feet square, and to be shallow recesses carved into the rock rather than real caves, each with a seated Buddha within, and many with wooden doors to protect them from further damage from the elements. There was one huge Buddha carved in the cliff, the only immediately striking work. The guidebooks spoke of a dizzying network of stairs and ramps to reach the individual caves, but this had just been replaced by a high quality paved walkway with elegant carved stone balustrades and an efficient one-way system, along which flowering plants and creepers had just been planted. We were extremely impressed by the huge investment that was being made in tourist infrastructure that was really in excellent taste, albeit slightly disappointed by the site.

Giant Buddha at Bingling Si

Decorated cave at Bingling Si

For an extra payment, we were offered a 10-minute trip in a topless four-wheel drive vehicle up the empty river bed at the foot of the cliff to visit a working Buddhist monastery on a peaceful hillside. We found the elegantly red-robed monks only too ready to leave their task (chopping cypress leaves to burn for incense) to show us round the mostly rather tawdry statues and paintings. In front of one Buddha, there were a group of little figurines in what looked like wax, perhaps 6-9 inches tall. They turned out to be ex-votos made by the pious out of mutton fat (and there was indeed a slight rancid smell). I asked what happened to them in the long run, and the monk answered rather sheepishly that the monks ate them. On our way down, we offered one of the monks a lift and took his photograph, in preparation for which he carefully adjusted his robe to a more becoming angle.

The elegant monk at Bingling Si

We are becoming expert in Chinese loos. The ones in the (mainly 3-star) hotels where we are staying are Western style, and soft sleeper station waiting rooms have both the Western and the squatting sort. On the whole, the western-style ones flush satisfactorily, although there is almost invariably a basket for the loo-paper as the drainage system cannot take paper – just like Greece in the 1960s and 1970s. Everywhere else, however, what my grandmother used to call “foot-steps in the sand” are the norm. The smartest ones are in cubicles with their own flushing mechanism. Next down the scale are cubicles with no door (or an unlockable one) and partitions only three foot high, so one can converse with one’s neighbours over the top (all loos are however segregated by sex). Then there are completely open-plan communal ones, with a tiled surface or concrete block in which there is a row of slits over which the loo-goers squat; below is a tiled or concrete channel and every few minutes, a self-flushing mechanism sends a stream of water along the channel to flush everything away. The most basic is similar, but without any flushing mechanism; presumably a nightsoil collector periodically cleans them out. Even the smartest smell.

******************

Zhangye, Gansu Province, 19-22 May Another overnight train took us some 450 km north-west to Zhangye, in the Hexi Corridor, the narrow strip of land between the Qilian Mountain range to the south and arid desert to the north through which all silk route travellers to and from Lanzhou had to go. One of the guidebooks said that Zhangye was relaxing and pleasant (Marco Polo apparently liked it so much that he stayed for over a year), so we had elected to spend three full days there. We began to regret this as soon as we arrived. The hotel was particularly lugubrious, and the weather – which in Xi’an and Lanzhou had been like a hot English summer’s day – was cold and rainy, a dull steady drizzle dampening to both spirits and person. The only benefit was that the rain also damped down the pollution from a big factory in the middle of the town spewing out evil clouds – it was interesting to note that the raindrops on my anorak and glasses left a very perceptible residue of concrete-coloured dust when they dried. To minimise weight, we had very few changes of clothing – Jenny and Kathryn had two pairs of trousers each and one skirt, whereas I had extravagantly supplied myself with two skirts as well as two pairs of trousers. Our clothes moreover were all lightweight. So we were badly equipped for anything other than summery weather. I put on my heavier pair of trousers, all three of my T-shirts, my old red woolly cardigan (which I noticed belatedly was full of moth-holes) and the lightweight anorak that I had bought for the trip and still did not really feel warm.

Despondently, we traipsed the streets (in the usual grid-pattern), seeking out the few, not very interesting, sights (Drum Temple, Bell Temple). We went into the town’s bookshop but could understand nothing except for the books on learning English. Next we visited the town’s “department store”. The ground floor was full of counters of mobile phones, ever smaller and more sophisticated (the mobile phone has really taken off here, with reception even in quite remote areas; in one place we saw a beggar talking into his phone with one hand while holding out the other for alms). Upstairs, the shop was really just a covered market for a lot of individual businesses selling everything from bras to stationery. I bought a most efficient magnifying glass for about 50p to read the tiny Chinese characters in my pocket dictionary – although I found that, as my eyes became attuned to them, they were no longer so hard to read and I hardly used it.

Street scene in rainy Zhangye

At one point we blundered into what turned out to be a sort of vernissage: a local artist displaying his drawings. They were mostly in pen and ink in the Chinese style, although with some colour, and the artist’s signature work seemed to be prawns – there were half a dozen really quite attractive drawings of whiskery prawns. But many of the other works, we were amused to see, were of fluffy kittens that would have done well on any chocolate box. The middle-aged artist and his sponsors greeted us warmly and we were lined up next to him and his wife to be photographed, presumably to appear in some local newspaper as important Western guests.

We had saved up the town’s main sight, a giant reclining Buddha, for the next day, to eke out such meagre cultural fare as existed. It was indeed most impressive, 34 metres long and the largest in China, but in restauro and covered in scaffolding, so we could do no more than glimpse giant toe-nails and huge draperies between poles of scaffolding. On either side, there stood half a dozen larger than life-size “holy warriors”, each with its own different characteristics – one was skeletally thin; another fat and jolly; one was black and fierce; and yet another was scratching his ear. We soon realised that this precise group of identifiable figures was reproduced in many Buddhist temples, but infuriatingly had no work of reference to explain what each represented. I had taken the precaution of purchasing a learned book about Buddhism before leaving London, but while it explained the doctrinal differences between the various Buddhist sects in tedious detail, it touched on the iconography hardly at all.

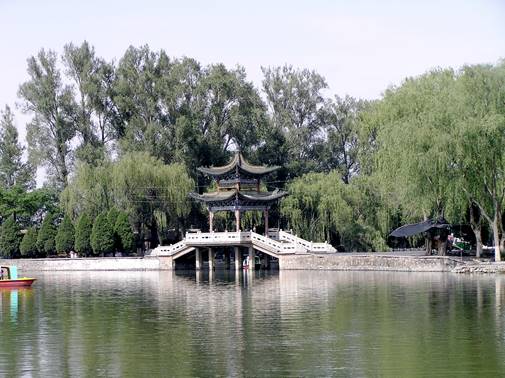

By the time we had seen the reclining Buddha and the other attractive buildings in the temple complex (including a little museum of paintings and drawings where we were told by a notice that “wandering among them, one can experience spiritual peace and harmony in the refined artistic atmosphere” – the Chinese are rather keen on telling one how one should be feeling), the weather had pulled itself together and we were feeling a lot more cheerful. Like most of the cities that we visited, there was a park full of little pagodas, bridges, cafés and old men gambling. There was a lake in the middle and we hired a pedalo boat. We were able to go right up to two terns sitting on a post in the lake. Many of the other boats on the lake were occupied by students from the nearby university, who would pedal themselves rather alarmingly to within feet of our boat and ply us with questions in fractured English.

Tile art in a temple in Zhangye

The pedalo lake at Zhangye

We discovered that most of the young had at least some command of English, and in one noodle-bar the monoglot restaurant owner dragged her 11-year old daughter out from some nether region and sat her down at our table to practice her English on us. She told us that she had been studying English for three years. She had achieved remarkable fluency and even her accent was reasonably comprehensible, perhaps because her school’s English teacher was an Egyptian (we usually found that even when people know the English words, their accent was so impenetrable as to make it hard to realise that they were not speaking Chinese). Nevertheless, having to make a prolonged conversation with our schoolgirl as we ate our noodles was pretty excruciating, although we were well rewarded by the fact that it was the cheapest meal we had in China, a mere 9 yuan, or some 70p for the three of us.

Once the sun was out, Zhangye had become a most attractive city. The women’s umbrellas were still up, but now used as sun-shades (a lot of care seems to be taken to preserve a pale complexion; the chief item of head-gear on sale was an eye-shade of the type that newspaper editors used to wear in old American films). The main square, previously a grey, wet and windswept open space, became a relaxed Mediterranean-style piazza, full of activities, especially on Sunday, when the citizenry turned out in force to fly kites, play cards and incomprehensible board games, or simply sit on benches in the sun. One whole part of the square had turned into an open-air cafe with tables and umbrellas, and a giant screen projected a football match. It was hard to reconcile the apparently relaxed and happy people in their multi-coloured clothing, including many Darby and Joan old couples, with the stern mien of the drably blue-suited crowds going about their earnest business that I remembered from my last journey to China in the 1970s. A slight reminder of those heavily collectivised times was sparked by a huge assembly of schoolchildren on the Sunday afternoon. They appeared to consist of three separate bands, 50 or more strong, each playing discordantly different music. But as the performance drew to an end, at some invisible signal the children suddenly formed up into orderly rows and wheeled round in formation into the shape of a giant star.

Our hotel had a sign in the lobby, for once in perfect English, saying “Pets are forbidden in our hotel. If you want to purchase any pets, please do it after your checkout lest any unnecessary troubles occur”. We never discovered what sort of pets visitors might want to purchase in Jhangye. On the whole there are very few pets anywhere to be seen – just the odd small dog or cat or caged bird.

Almost all the restaurants are in “Food Street”, an attractive pedestrianised way with lots of red lanterns (the traditional sign of a restaurant). At the end there was an open area where on Saturday evening some men arrived with a truckload of pottery vases, wrapped in strong-smelling damp straw. By Sunday morning they had all been unbundled from their straw and were on sale. Many of them were huge – up to five feet high. They were decorated in both traditional and modern styles and one had to admire the handiwork that had gone into them, but sadly none of them was really attractive, either in shape or decoration.

Vases being unpacked at Zhangye

The vases for sale at Zhangye

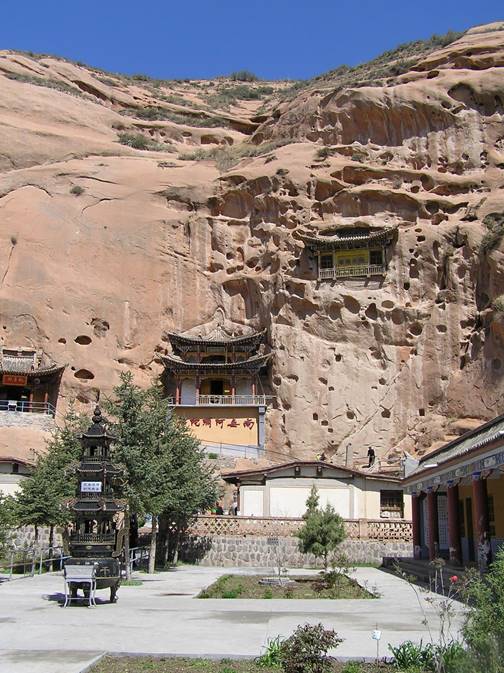

On our final day, we hired a car with a driver to take us out to a temple called Mati Si up in the foothills of the nearby snow-capped Qilian Mountains. It turned out to be a large area that had been turned almost into a sort of theme park, with some pleasant but undistinguished Buddhist caves and a number of similarly pleasant but undistinguished temples, and members of the local minority tribe, the Yugu, dressed in colourful national costume, acting as guides and giving dancing displays to the visitors (all Chinese apart from ourselves). As in most of the sites we visited, there were enormous numbers of steps to get to the various monuments. At one point, a notice pointed up what looked like about 30 steps to viewing platform. When we reached it, however, we realised that it was but a stage on the way up, and the real viewing platform was some 400 steps further up. The views were spectacular, with snow peaks to one side and a fertile plain to the other.

Temples in the cliff at Mati Si

At lunch-time, our driver led us firmly to one of several shamiana type tents where we were installed for a Yugu meal with full folkloric trimmings. As we entered the tent, two Yugu girls sang us a song of welcome and presented us with a sort of quaitch of the local (vodka-type) fire-water, out of which we each had to drink in turn. During the meal, a soundtrack was played on a large video monitor, and the girls gave us a dancing display as we ate. The tent was divided in two by a cloth partition, and on the other side of the partition two other girls were giving an identical display to the same sound-track to another set of (Chinese) lunchers. The meal itself, ordered by our driver, was interesting. It started with a bowl of what we decided was probably hot yak buttermilk. Into this we stirred a sort of powdered barley as a thickener, and a large pat of yak butter. Savoury doughnuts were then dunked into it, and finally the soup was drunk from the bowl. Our main course was two sorts of mutton, ribs boiled in some aromatic broth and the most delicious roast shanks or knuckles; local noodles that had the consistency of elastic bands; and three or four different plates of vegetables, all good, especially a dish of tomatoes sprinkled with sugar (which we discovered was a regular in that part of the world). The boiled mutton dish included two sheep’s hearts. Our driver picked out one with his chopsticks and when I eyed it appreciatively immediately handed it to me and tried to insist that I eat the other one as well – after some tussling with chopsticks we ended up by finding a knife and cutting it in half. There followed some excellent yoghurt with honey, by which time we were feeling more than replete. But one must never forget that Chinese meals end in soup. To our horror, large bowls of noodle soup arrived. Our driver tucked in with gusto, but I fear none of us could face even a mouthful, especially as the sweet taste of the honey was still lingering in our mouths.

This was probably the only occasion on which we had a proper meal, i.e. with all the right courses (as our driver knew what to order); it was also at 240 yuan for the four of us (i.e including the driver) some two or three times more than we paid for any other meal, which caused us outrage until we reflected that, dancing girls and all, the total in sterling was less than £20.

After lunch, the driver dragged us off to a full-scale Yugu dancing show that was scheduled to begin at 3 pm on a large stage labelled “Song and Dance Hall”, and that was included in the price of our entry ticket to the site. This was one of the few things in China that did not start on time, and after a wait of half an hour we got fed up and went for a walk instead along one of the many paths in the hills. All in all, however, the visit to Mati Si was a fun expedition which we much enjoyed.

Trips outside town also gave an interesting, if tantalisingly brief, glimpse of rural life. Much has been said about the continued poverty of the Chinese peasantry and the lack of trickle down of economic wealth to the countryside. I must say that we saw no real poverty around Xi’an, Lanzhou or Zhangye, perhaps because they were near enough to reasonably prosperous towns to have benefitted from at least some trickle down. Indeed, there appeared to be impressive building activity going on in quite a few of the villages, with rows of new housing being built. The traditional North Chinese dwelling has a blank mud wall facing the world with painted metal doors leading into a courtyard surrounded on two sides by dwellings for people or animals (the courtyards can be bigger or smaller – some were large enough to have trees and vegetables growing in them, and the biggest houses had further courtyards behind). Sometimes this format appeared to be being followed; in other cases the authorities appeared to be imposing more Western-style houses, often with extraordinarily fanciful architecture for village houses – porticoes with columns, for instance.

The agriculture appeared to be still very primitive, although some of it no more so than say parts of Poland. There were a few tiny tractors, but also still people using hand-ploughs, and small paddies are still the norm. But polytunnels have definitely reached China. Indeed, we assumed that at some stage some central writ must have gone out resulting in polythene sheeting being installed indiscriminately regardless of whether it made sense, as there were large numbers of structures obviously built for use with polythene and now deserted. Crops round Xi’an and Lanshou were mostly rice, maize and fruit. As we went west, first the rice gave out, and gradually a generally cultivated landscape yielded to desert punctuated only by occasional oases. Even in the relatively well-watered areas round Lanzhou, there were places that were leached out and barren, presumably from unsustainable cultivation methods.

*********************

Jiayuguan , Gansu Province, 22-24 May We travelled on by bus further north-west to Jiayuguan, a 150 km journey that took some five hours. The bus left the bus station half empty, and then stopped two or three times by the side of the road as it left time, for sometimes lengthy periods, picking up more passengers. As the first such stop was only just outside the bus station, we were initially somewhat puzzled, but quickly realised that what we were seeing was private enterprise by the driver. We did not see any money change hands, but were aware of confabulations taking place just out of sight and assumed that notes were being discreetly passed, to the benefit of all parties but the bus company. This happened on every long-distance bus that we took.

The bus was pretty luxurious, complete with a video showing what I christened “noodle Westerns” – films about the American West but obviously made somewhere like Hong Kong and featuring Chinese characters performing feats of kung fu well outside the capabilities of even the best doubled American cow-boy. The Westerners were usually portrayed as fat, ugly and xenophobic, trying to drive the brave and industrious Chinese out of town, but with one sympathetic white man who befriended them. The Chinese were all very European-looking, and at a casual glance it looked like any Western, until one noticed a kung fu movement or an episode of extreme and noisy violence outside even Clint Eastwood’s canon of acceptability.

Jiayuguan is a windblown town of huge wide streets, as always on the traditional grid pattern but with the main trunk road cutting across the town at an angle, as if the town-planners had decided deliberately to ignore the way the road ran. The town’s importance came from the fact that it is at the western end of Hexi corridor. Enormous rebuilding was taking place, with huge office blocks and blocks of flats going up. Our search, guidebook map in hand, for the “night market” (a market found in most towns round here that opens only in the evening and consists mainly of stalls selling kebabs and other Chinese-style fast food, together with some rickety tables) proved vain as the whole complex of little streets in which it used to be had been swept away in the frenzied construction activity. It was far from clear where this apparent prosperity came from, as the town is surrounded by desert. The town is still very much a mixture of old and new – a fair number of private cars (although not nearly as many as in the east), but also lots of bicycles and carts – one of the more engaging sights was a man pushing a handcart containing a couple of dozen spherical bowls of goldfish.

We stayed in an excellent modern 4-star hotel, which for once knew about our booking. The only other westerners were a group of 17 hard-hatted German construction engineers helping with the building programme. They had their uses – the rather good restaurant near the hotel had its all-Chinese menu annotated in German, including helpful comments like “lecker”. Like many of the other hotels we stayed at, the carpets in the lifts were changed daily and had the day of the week written on them in Chinese and English. The lifts here had the added attraction – soon to become a profound irritation – of a recording of Beethoven’s Für Elise that started up as soon as the lift doors shut, only to be cut off short a few bars later when the lift arrived at its destination. The lift was modern and pretty rapid, so it would probably have needed a journey at least to the top of the Empire State Building for poor Elise to finish her sonata.

There is almost nothing for the tourist in Jiayuguan itself, but it is the jumping off place for two particularly spectacular desert sites: the last fortress of the Great Wall, and the very end of the Wall itself. The fortress was built by the Ming in 1372, strategically between the snow-peaks of the Qilian Mountains to the north and the forbidding black Mazong Mountains to the south. It is some 5000km from the eastern end of the wall, and must have seemed like the end of civilisation to the unfortunate garrisons who had to man it, as they looked out onto the endless desert to the west, inhabited only by hostile sharp-shooting nomads. The fortress is huge, with an inner and outer wall, and must have accommodated hundreds of men. Apparently the Ming imported Han peasants from the east to set up farms on the China-side of the wall (where there are oases), both to provide food for the garrison and to help “civilise” the country – as civilisation to the Chinese is synonymous with sedentary agriculture. The green on one side of the wall must have made the pitiless desert on the other side seem yet more desolate and eerie.

Looking towards the endless steppes

Some 8 km further west along the wall, we visited the so-called “Overhanging Wall”, a section of wall that connects the fort to the next mountain range. It has been well restored, and this was our opportunity to walk along the wall. Walk is hardly the word, as it ascends steeply up the mountains and down the valleys, so most of the time one is climbing vast numbers of steps up to a little lookout point at the top of the mountain before the wall plunges down into another valley. The views are fantastic, and Jenny, who has visited the bit of Great Wall near Beijing that is on all tourist itineraries, said that it was just as impressive – although the wall here is built of mud rather than stone.

The “Overhanging Wall” snaking up the mountain

Tourist transport, complete with ladder, waiting for custom near the Overhanging Wall.

Perhaps the most atmospheric place, however, was the very western end of the wall, a place called First Beacon Tower built later (in the 16th century) where the wall meets a natural termination point, a huge river gorge, beyond which there is still near absolute wilderness. There is not a lot to see – a crumbling mud tower at the end of a crumbling section of wall. But the Chinese tourist authorities have made the best of it by constructing a viewing point actually over the gorge but cunningly concealed so it is not visible from the tower; and by throwing a narrow and rickety suspension bridge over the gorge itself, across which braver tourists can venture (it is built of wire and wooden slats and sways alarmingly as one walks). On the other side, they are building a number of huts, apparently showing what a garrison village would have looked like, complete with furnishings and wax models of soldiers – an impressive effort. I may say that there were no tourists, apart from us and a small group of Chinese men, to benefit from all these facilities (including the inevitable visitor’s centre with souvenirs for sale).

A crumbling section of the Great Wall

The western end of the Great Wall with First Beacon Tower

The river that divided Chinese territory from the steppes at the end of the Great Wall.

****************

Dunhuang, Gansu Province, 24-25 May

Dunhuang is some 200 miles further west and we left Jiayuguan at 11 am in a bus that was supposed to take about 6-7 hours but took a hair-raising nine. It seems that there was a perfectly good tarmac road between the two cities. But the government has decided to build a brand new dual carriageway alongside the existing road, with an eye no doubt to the military as well as the developmental benefits. In other countries, new roads tend to be built in tranches of 10-20 kilometres, and the old road is preserved until the new is ready. Not here. Some 100 kilometres of new road was under construction all at once (albeit without any very obvious signs of active work on most sections; in that respect at least it was no different from the West). Moreover, the construction work had spilt out onto the old road, so the traffic had perforce to leave the old road at frequent intervals and forge new parallel tracks alongside, across the gravelly desert. Inevitably, as one track became over-used and impossibly bumpy, new ones were created, and the end result was a tangled skein of intersecting tracks with buses, lorries and the odd private car (scarcer in this part of the country) weaving from one track to another in a haze of dust. Our brilliant bus driver performed with the best, but this was not a trip for those who dislike bumps.

Dunhuang is still just in China proper, but already showing signs of the West, more impoverished than previous towns and with a noticeable ethnic minority population. The town is the jumping off point for the Mogao caves, probably the best Buddhist caves in China, so it is relatively touristified. Even so there were very few Westerners. We were thrown together with an attractive young French couple (a particularly dishy man in French film-star mode with whom Kathryn was much taken); and a less attractive New Zealand/white South African couple who been running in the “Great Wall Marathon” near Beijing (they both tended to make despairing remarks about the lack of enterprise of the Maoris and Blacks in their respective countries, “these people”, and we had determinedly to bite our lips and change the subject). As so often happens in way-out places, we kept meeting them again as we followed each other around along the silk route.

Dunhuang itself was nothing special. There was however an attractive night market, where one could sit at tables in a well laid out modern plaza and order kebabs or noodles from distinctly unmodern stalls around the sides. The lamb kebabs were delicious, and for once we managed to make the stall-holder understand that we wanted some with chilli and some without. We also had a good meal in Shirley’s Café, set up by a Chinese family with American connections to cater to the Western budget traveller market – so a menu in English. The café keeps a book – or rather two or three books – in which travellers are invited to comment on and offer advice on the different places they had visited. Most of the comments were predictably by back-packers, as no group would ever eat here. These books provided the perfect entertainment while we waited for our food. There was an extraordinary divergence of views between the different travellers, with one entry for instance complaining about the dourness of the Chinese and the next taking violent issue with these sentiments and praising Chinese friendliness.

The Mogao Caves

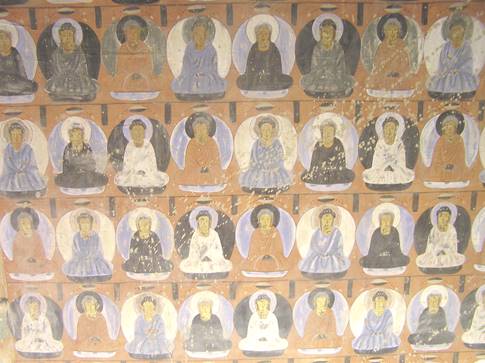

The Mogao caves, some 25 km away, came fully up to expectation. They are effectively temples excavated out of the rock, some very large indeed. The earliest supposedly date from the fourth century AD when monks coming along the silk route began spreading Buddhism, and it soon seems to have become the thing for rich merchants to pay for a temple to be excavated and decorated – there are pictures of the donors rather like those in medieval Italian paintings. There are some 600 caves in a better or worse state of preservation, but only a few are open to the public. One is obliged to take a guided tour, which we did with the two young Western couples, and each tour visits nine or ten caves. As culture-gluttons, we took a second tour in the afternoon and persuaded the guide to take us to a different set of caves (the caves seem to be opened in some sort of rotation to avoid too much wear and tear).

Cave painting at Mogao

All the caves are different and we soon began to recognise the styles of the different eras. But there are certain common patterns. Almost every cave has a large painted figure of the Buddha (or other senior figure) with attendant holy warriors or boddhisatvas. And the walls of the caves are covered in paintings, some of pastoral secnes, some of dancers and angels, and some simply of endlessly repeated images of buddhas, like wallpaper – hence the expression “thousand Buddha cave” that had mystified me in the descriptions that we had read beforehand. The caves were sealed and abandoned in the 14th century, and only rediscovered in 1900. One of the most exciting discoveries was of a small sealed room off the biggest temple into which thousands of early Buddhist manuscripts and paintings from all along the silk route had been crammed by some 14th century monk, no doubt to conceal them from some barbarian foe. This discovery attracted that imperial cultural predator Aurel Stein and a Frenchman in a similar mould, who carted off large quantities of the manuscripts and paintings for the British Museum and Louvre respectively, where they remain to this day. We could peer into the tiny room where the manuscripts had been found, and it was a moving sight.

Part of thousand Buddha cave painting at Mogao

There were quite a lot of Chinese tourists, even though it was a weekday, and preservation of the caves is clearly going to be a growing problem as the number of tourists increases. The guide pointed out to us the changes in the flesh colour of some of the paintings over just the last few decades as a result of opening the caves to visitors, even though flash-lights only are allowed in the caves. The authorities have built a huge and well laid out visitor centre in which they are creating replicas of the best caves, and no doubt in the future, as in Lascaux, only professional archaeologists will be allowed into the caves themselves. So we counted ourselves lucky to have come when we did.

The sand dunes

These constitute Dunhuang’s other tourist attraction. They are about 5 km out of town, and we hired bicycles to go to them. The dunes are huge, rather like those outside Bordeaux, and have been enclosed so that visitors can only explore them after paying a hefty entrance charge (the comments in the books in Shirley’s Café expressed indignation at the size of the charge – perhaps some £5 – and suggested various back ways by which the unscrupulous could sneak in for free). They are made of best quality yellow sand, just like in picture books, and the wind had blown the sand into wonderfully sharp edges. Climbing them is a major effort. Kathryn gave up almost immediately because of her bad head for heights. I managed the first dune, but then quailed at the ever-succeeding higher peaks that were revealed beyond. Jenny of course was not a bit put off, and promptly moved onto the next dune, on which no tourist had yet ventured that day, thus shaming some much younger male Chinese tourists to follow in her wake. She made clear that if we had not been waiting, she would have gone on to the highest dune, several peaks further on.

On the way to the sand dunes at Dunhuang

Sand dunes at Dunhuang

One of the guidebooks suggested that one could slide down the dunes, something to which I was much looking forward. But the inertia of the sand made that impossible, although there was a rather exciting run-cum-slide motion that one could do down the dunes at speed. Dunhuang had had one of its very rare rainy days on the previous day, and it was fascinating to see that occasional tiny seedlings were already piercing through the sand.

****************

Turpan, Xinjiang (Sinkiang) Province, 27-30 May

On to Turpan by overnight train, arriving at an unearthly hour of the morning – fortunately, as the Chinese hotel starts at 6 a.m, we were able to get in a nap before breakfast. The latter, we found, was only available in our rather indifferent hotel if there is a group staying, which there was not, so we had to walk for several hundred yards to a sister hotel.

Turpan is in a deep depression in the high plateau, only just above sea-level, and is famously the hottest town in China. It is indeed very hot, although far from the 45º that it reaches in high summer. Although the whole of China officially operates to Beijing time, we are now so far west that the official time is way out of kilter with what the sun is doing. The inhabitants deal with this simply by pushing everything back a couple of hours, so eight is impossibly early for breakfast; few lunch before two; and nobody starts dining until at least 9.30 p.m. Indeed, the whole town only really comes alive at about nine in the evening when the worst of the heat is over, and the place is buzzing until well after midnight.

We have now left China proper and the majority of the population are Muslim Turkic-speaking Uigurs. They have little liking for the Han Chinese, as we soon discover. The younger people are all busily learning English, and more English is spoken here than in some of the towns further East. Teenagers come up to us to practice their English, and we ask one girl how many languages she speaks. She answers “Uigur and English.....and Chinese”, the latter firmly relegated to a third place. Education – at least for the majority population – is in Uigur with Chinese taught as a second language, and it struck me that the need to master the 6-9,000 Chinese characters required by an educated person (and which takes the average Chinese-speaking school-child some six intensive years of study) must be a very effective barrier to advancement by Uigurs in the Chinese administrative, economic or commercial world. Although all looked peaceful, there was the odd sign that it might not always be thus, e.g. a Chinese military convoy driving ostentatiously along the main street.

Despite the heat, Turpan is a delightful town, the main roads all planted with shade trees and a most agreeable pedestrianised main artery covered by vine trellises and lined with restaurants with tables under the trees. In the evening, the whole population seems to be out enjoying themselves eating and drinking and chatting and playing games – including billiards, the central area being well supplied with outside billiard tables with light-bulbs strung above them. There is also an extensive bazaar – the first really good one that we have encountered. I negotiate for a Uigur cap for my godson and for some very pretty stoles made of silk and wool, an exercise into which the old Uigur shopkeeper (straight out of central casting with his embroidered cap, wizened face and wispy beard) enters into with gusto, throwing his eyes and hands up in grand theatrical gestures at my suggestions as to the price I should pay, but finally settling for a fraction of the original with great good humour – so I get two shawls and an embroidered cap for about £6. The bazaar also has a wonderful yoghurt stall at which one sits at a low table and is served bowls of freshly made yoghurt with the sort of delicious crust on top that I remember from Greece and Turkey in the 1960s. We go back there again and again.

Pedestrianised boulevard at Turpan

The first day we walk in the heat of the morning (mad dogs and Englishmen) a couple of miles out to the edge of the town, where modern buildings are soon succeeded by mud walls concealing Uigur courtyard houses, some incongruously decorated with paintings of alpine scenes. Our objective was a handsome brick-built mosque, faintly reminiscent of the mosque in Bukhara. A group of Uigur tourists from Kashgar is also visiting the mosque and we reflect that it is good that there is a Uigur middle class prosperous and educated enough to be on such a visit. They instantly fasten on to us and we are made to stand next to different members of the group in turn to be photographed with them. There is one woman in particular who firmly clasps her arms around us to keep us in place.

Amin Mosque on the outskirts of Turpan. It was built in 1779 and the minaret is the tallest in China

We walk back into town, where we meet the athletic New Zealand/South African couple who are planning a 34 km round trip by bicycle that afternoon to visit a nearby ruined city. Jenny’s eyes light up, as she has been trying vainly for several days to get Kathryn and me onto bikes – I have been resisting as it is 20 years since I have been on a bike and I am not sure I trust myself for other than short journeys; and both of us are terrified by the local traffic. We are in any case by this time almost melting from the heat (it must be 90º fahrenheit at least) and opt for a siesta – for the first time on this trip. The amazing Jenny, however, sets off with the young couple in the full heat of the afternoon sun (mad dogs and still madder Englishwoman).

We quickly discover that there is a local Mr Fixit called Mamet who has monopolised the organisation of tours from Dunhuang. He is loosely based in John’s Café (the café-restaurant run by an American Chinese that is the budget travellers’ gathering place), but pops up everywhere as if by magic. He was on the minibus that collected passengers from the train when we arrived, presumably looking out for likely tourists, and pops up regularly at our hotel or at the breakfast hotel (where he seems to sleep), as well as hailing us every so often in the street. He does run a very slick organisation, and we use him to hire a car to take us to the local sites (this formula works quite well if the driver is given clear instructions as to where to take us, as we have him for the day and can stay as long as we like in each place).

Turpan is in the middle of a large oasis and there are two ruined silk road cities nearby, Jiaohe and Gaochang. The buildings today are little more than lumps and humps of baked mud much the same colour as the surrounding desert (at some point the oasis presumably retreated, cutting off vital water supplies, although there are still apparently some working wells). But one can make out the outer walls and the street plan, and there is enough left of some of the buildings to see that they must have been large buildings of up to three stories. The sites are huge, and there are so few tourists that one has not to go far to have the places more or less to oneself. Wandering alone around these ruins in the hot wind is immensely romantic. To my delight I find ant-lion traps in the sand; almost the only vegetation is the occasional sprawling caper plant. At the moment, apart from occasional notices saying things like “Collapsing, keep off”, one can wander or climb anywhere at will and there is little to show that these deserted cities are tourist sites. But as the numbers of visitors increase, no doubt areas will be fenced off and tourists restricted to walkways, so (as at the Mogao caves) we feel that we have come just in time.

Ruins of the ancient silk route city of Jiaohe

Kathryn and Sophia at Gaochang

Gaochang, the most visited of the two cities, has donkey carts that will for 20 yuan (£1.50) transport one to and from the far end of the site (about a mile) where there are the remains of a large Buddhist monastery. Each cart takes a dozen people. We spurn the carts and walk, but decide to take one back as we are offered a bargain rate of a mere 6 yuan by one of the drivers. As we approach the exit, with its official ticket office etc., the cart stops short and we are invited to dismount, and we realise with amusement that, just as with the buses, the drivers of these carts are not above picking up “unofficial” passengers, who must be dropped off before they are noticed by officialdom.

Tourist transport at Gaochang

These ancient cities are not the only interesting places around Turpan. There are also an ancient underground aqueduct bringing water from the mountains like the qanats in Iran (commercialised into a rather dreadful theme park); the red sandstone Flaming Mountains (which one can see perfectly well from the road, but as they figure in one of the great works of Chinese literature, that has not stopped the tourist authorities from creating a visitor centre with shops, camel rides etc.); some very ruined “thousand buddha” caves; and above all the Astana Graves. These date from the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) and contain the remains of important locals. Only a couple are open. One descends stairs to small subterranean chambers with simple but wonderfully fresh painting. Again a site that will not stand up to mass tourism, so we are lucky to have come when we did.

Caves near Turpan

More tourist transport – Bactrian camels

There is an excellent small museum in Turpan with about a dozen well-preserved mummies from the Astana Graves, their clothes and shoes still very much there. They include a pathetic pregnant woman who died with her child in childbirth. A lively and well-informed English-speaking girl on the museum staff attaches herself to us and shows us round for free – the best guide that we encountered on the whole of our trip. As we are leaving, an American “archaeological” tour group arrives. We have already been made aware of their existence by a large red and white banner in the town saying “CITS [the local travel agency] welcomes the American Archaeological Tour”. They are following the same route as us, and from then on we bump into them several times. They are being bear-lead by a white-bearded American archaeologist based in China with whom we quickly chum up – Jenny’s mention of Norman Hammond presses just the right button. It turns out that he is the only real archaeologist; the others are just middle-aged American tourists of the more cultured kind.

The Turpan oasis is famous for its vines, and local wine is on sale (generally alcohol – mainly beer and the local firewater - seems to be freely available pretty well everywhere we go in China). We take to buying a bottle of red wine every evening that we take back to our hotel bedroom with fruit, sultanas (a local speciality) and nuts bought from the market. The wine is no more than so-so.

Vineyards near Turpan

***********************

Kuqa, Xinjiang Province, 31 May-2 June

We travel to Kuqa by overnight train, across a spectacular mountain range, with the train having to double back on itself to manage the gradient. We followed a river valley most of the way, very spectacular. There were occasional closely cropped green flood plains with a silvery stream running through them, dotted with sheep, horses and shepherds. But for the most part the land was fairly barren and completely unpopulated. At many places along the line there are deserted settlements, which appear to have been deliberately demolished. Most of the smashed up buildings are quite modern-looking brick structures. We puzzle a lot about these. Possibly barracks from the Maoist era, when Xinjiang was a lot less settled; or perhaps Uigur settlements that were moved to a less strategic area; or perhaps a failed attempt at Han Chinese colonisation of this remote area. It was all rather sinister.

A view from the train

We arrive at Kuqa the unearthly hour of 2.45 a.m., and it is with some relief that we find an assembly of taxis in the station forecourt, as the station is a good 5 km from the town. The hotel is a good, well-modernised one, soon to be festooned with a large red banner saying “Welcome to the American Archaeological Tour”, who duly turned up a day or two later. The sleepy receptionist as usual seemed to have no idea that we were expected, but after some 20 minutes of parlaying and mutual incomprehension – watched over by our kind taxi driver, who clearly did not want to leave until he saw us settled – we were finally allotted two rooms.

Kuqa is the furthest west that I went, some 6-700 kilometres west of Turpan, and perhaps 1,000 kilometres west of Duanhuang (and nearer to 3,000 kilometres from Beijing). It is far more overwhelmingly Uigur than Turpan and the first place that we have visited that is definitely more third world than first, and where we felt that the majority of the population did not have a mobile phone concealed about their person. A dusty city on the usual grid pattern, its attractions for the tourist are quickly exhausted – a 19th century mosque of little charm; a wooden tomb; fragments of old mud wall. We came here partly because it was said not to be touristy, and one can see why. But the inhabitants are fascinating. Wonderful Uigur and Uzbek faces, some flat, red-cheeked and Mongolian, and others narrow and aquiline with deep-set eyes. The older men wear embroidered skull-caps and white wispy beards (the Han Chinese seem rarely to go white, whatever their age).

Old men in Kuqa

Traffic in Kuqa

The women are dressed in an amazing array of clothing, ranging from occasional near mini-skirts on the young and particularly daring to long gowns with trousers underneath. Most of their clothes are made of wonderfully garish and sparkling fabrics, with sequins and synthetic gold thread in abundance. The garb of the older market women appears to be a headscarf, often tied behind the head (no nonsense here about not showing one’s neck); a blouse and long skirt; beneath it ankle length white cotton knickers, the legs quite tight and with and broderie anglaise at the bottom; and knee length nylon stockings pulled over the legs of the knickers. Even the relatively young and fashionable with skirts only to mid-calf wear these knickers and stockings. At first I thought that they had their legs bandaged under their stockings and were suffering from dreadful ulcers, but the knickers seem to be the garment that acceptably satisfies the requirements of modesty and allows freedom to wear western style clothes for the rest.

Woman and donkey in Kuqa

The market women tuck their money into their stockings and think nothing of hitching up their skirt in full view of everybody to extract a roll of notes when there is a commercial transaction to be done. Many sit with their legs wide open, displaying a generous view of both stockings and knickers.

The other main reason for coming to Kuqa was that it was said to have a good Friday market. Perhaps we had too high expectations, or are too experienced market-goers, but it was not as interesting as we had hoped, with no livestock or colourful out-of-town tribal costumes. The market was spread out over the streets on one side of the river bridge that divides the old town from the new, and a constant stream of new arrivals came along the mud flats in the river-bed by horse-, mule- and donkey-cart. If one closed one’s eyes to everything else around, it could have been a road scene from 18th century England. The area under the bridge became a huge park for the carts and their steeds, while their owners took their goods and spread them out in the neighbouring streets. It was a comprehensive market with everything from fruit and vegetables through to nuts and bolts (literally), passing through inter alia piles of garish carpets; mounds of extra fragrant rose petals; forests of wonderful wooden pitchforks; rows of gaudily gilded metal chests; women sitting by the roadside with pottery bowls of yoghurt each with a little wooden board on top to keep away the flies; and of course endless kebabs and noodle-sellers (it is hard to go more than 50 yards in towns in this country without finding food or foodstuffs on sale). There were also strange arrays of what were presumably medicines – dried coiled snakes and starfish; bits of what looked like coral; and mysterious seeds and pieces of dried root.

On the way to market, Kuqa

Kuqa Friday market on the riverbed

Another market scene on the riverbed at Kuqa

Carts at Kuqa market waiting to go home

On the way from the Kuqa Friday market

The broom market at Kuqa

One street was the avian market – cages full of pigeons and ducklings, and down a little side alley middle-aged men each fondly but firmly clutching a single battered fighting cock – their scars no doubt an important selling point.

Doves on sale at Kuqa market

Outside Kuqa, we visited Subashi, yet another romantic ruined silk route city, deserted in the 12th century and now consisting only of lumps of coagulated mud brick. There were also some very early Buddhist caves outside Kuqa, with paintings still under strong Indian or Perso-Hellenic influence – apsaras; dancers making Indian-style shapes with their fingers; some figures with round eyes and others looking to be straight out of an early Persian miniature. Unfortunately, most of the figures had had their eyes or faces gouged out by offended Muslims, but the designs were still clear and good, in lovely blue, green and black colours. In the little museum attached to the caves, there was a beautifully carved, more than life-size erect marble phallus, the shaft decorated with curlicues and arabesques – like an early version of those ribbed condoms “for extra pleasure”.

The ruins of Subashi, ancient silk route city near Kuqa

From the caves we visited to a spring with a legend attached, although we never discovered what it was. We walked about a mile along a valley, very remote and beautiful, past the occasional picnicking Uigur family. At the end was a sheer rocky cliff with water seeping out from a number of points, making quite a strong flow at the bottom. Uigur women were washing their feet and filling bottles with the water, so it obviously had some desirable property.

During our stay in Kuqa we mainly subsisted on the typical Uigur fare of gristly kebabs and “pular” – rice rather deliciously flavoured with mutton fat and carrots, usually with a chunk of boiled mutton thrown in. We managed a good meal on Kathryn’s birthday, in a Uigur restaurant in a quiet courtyard – excellent kebabs; spinach ordered with the aid of the dictionary and yoghurt. On our last day, we ate in the hotel restaurant – the first time since Xi’an that we have done so, as most hotel restaurants we saw were grand, gloomy and empty. This, on the other hand, looked rather good, and judging by the amount of dining in private rooms that was going on was the only smart Chinese restaurant in town. There were both Chinese and Japanese tourists eating what looked liked scrumptious feasts at big tables. But once again, the menu was only in Chinese. Finally the hotel produced what was obviously a training book for hotel staff dealing with English-speaking guests. There were sample conversations about such things as paying by credit card or ordering fine wine – totally unrealistic in a city like Kuqa where a credit card dropped in the street would probably not even be picked up. The book did, however, include a list in English and Chinese of the main dishes served in a typical (eastern) Chinese restaurant – again most items far removed from what is on offer in the wild west of Xinjiang. But as most Chinese food is a matter of throwing some fairly basic ingredients together, we assumed that we would be safe enough pointing to an aubergine and garlic dish and a chicken with cashews dish on the menu. The aubergines duly came and were delicious, but there was no sign of any chicken. It turned out that there were no cashews. But infuriatingly, the staff decided just not to serve us rather than to tell us that what we ordered couldn’t be had.

This book seems to be in every hotel, and it struck me that they may all have to end designing their menus to match the dishes listed in the book, rather in the way that cheap Japanese restaurants are said to buy off-the-shelf plastic replicas of dishes to display in their windows and then work out how to cook something that looks like the dishes in question.

********************

Kuqa to Beijing, 2-3 June

Kuqa marked the parting of the ways as I began my long journey back to London (starting with a 16-hour train journey to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang) and the others went on to spend another week going to Kashgar and round the south of the Taklamakan Desert. We all went off to the station together at 9 p.m. Not many trains stop at Kuqa, and it was much smaller and less well-equipped than any of the previous stations we had seen. The only waiting-room was of a typical third world type – rows of uninviting benches, no shops selling snacks, the few naked light-bulbs failing to illuminate adequately the huge, high room; and odorous toilets making their presence known. The one saving grace, here as indeed everywhere we went in China, is that there are very few flies: perhaps the Maoist campaign to kill flies really worked. (We also saw very little spitting – a Chinese habit that all the guide-books warned about, but which seems to have been successfully eliminated by the anti-spitting campaign that the government have been running to improve the image of the country for the Olympics.)