THE FOUR LADIES’ TRIP TO CENTRAL ASIA MAY-JUNE 2007

Being an account of a journey through Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan by Jenny Bacon, Sophia Lambert, Kathryn Morton and Dinah Nichols, all retired senior civil servants.

When we went to China last year, we travelled almost everywhere by public transport – local train or bus – and we did not have the services of a guide. For our trip to Central Asia, with its more exiguous transport network, we were persuaded by our travel agent to rely on hired minibuses with drivers, especially as we wished to go to all sorts of out-of-the way places. An English-speaking guide was imposed upon us in Turkmenistan and we also had one for the mountains in Tajikistan.

Dinah joined us only in Bukhara, and Kathryn left us in Samarkand to fly back to London where she had engagements. So for most of the trip there were only three of us. Our hotels were booked in advance. We booked two double rooms, taking it in turns to share according to an ingenious rota worked out by Jenny to ensure that we all had an equal number of nights alone.

Our chief aim was to visit silk road sites, but we also made a point of visiting any other interesting place that was not too far off our route and we added a couple of days trekking in the mountains of Tajikistan.

What follows does not say much about the major sites, as they are well described in various guidebooks. The photographs were taken by Jenny except where otherwise stated.

Central Asia: a potted history

The area lies between the Caspian Sea and the Pamir mountains that form the formidable frontier with China. It is watered by two famous rivers, the Oxus (now the Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (now the Syr Darya) and a third called the Zarafshan. Away from the rivers, it consists almost entirely of deserts and (in Tajikistan) of mountains. The cities that made their living from silk road caravans needed a source of food, so they grew up in the oases near the rivers. Many of these cities developed sophisticated civilisations. They were always under threat from nomad incursions from the desert, invasions by their neighbours or from changes in the course of the local rivers. So there was a constant churning of cities and dynasties. There were, however, a few really big players who left a lasting imprint on the area.

The first was Alexander the Great, who conquered most of the area in the 4th century BC. Although he did not stay long, hellenism proved a lasting influence on the art of Central Asia. Following him, the Parthians and then the Persians controlled large parts of the area and the Turks were also active. In the 7th century the Arabs came and islamicised the area, though they did not ever really rule the area, and the Turks and Persians remained the main outside influences. Genghis Khan with his Mongol hordes came down from the northern steppes in the thirteenth century, leaving death and destruction in his wake. About a hundred years later came Tamerlane (or Timur the Great as he is now known locally; Tamerlane is a corruption of “Timur the Lame” and references to his lameness are now frowned upon), from the same Turkic-speaking nomad group. He also brought death and destruction, but in his own back yard of Samarkand and its surrounding area was responsible for many fine buildings and a flowering of the arts. After that, with the withering of the overland trade routes as goods were increasingly transported by sea, there were centuries of small khanates. In the 19th century, the area attracted serious Russian interest, giving rise to the Great Game, and from then on Russia was the dominant power. After the Russian Revolution the area was divided into the five current states and incorporated into the Soviet Union. In 1991, although the populations had voted massively against leaving the Soviet Union (and losing Russian subsidies), Russia foisted independence upon them. Even today, it seems that some people still hanker after Soviet times when every body had a job for life whether they worked or not. Our Turkmen guide quoted one acquaintance harking back nostalgically to the old days “when we could just sit back and eat”.

******************************

A ruined mud-brick silk road fortress

We started in Turkmenistan, a large desert country about the size of Spain, although with a population of only some five million. It lies between the Caspian to the West and the Oxus to the east and to the south has borders with Iran and Afghanistan. Its first president after independence, Niyazov, reinvented himself as “Turkmenbashi”, leader of the Turkmens, on the model of Kemal Ataturk. He developed a strong personality cult, using the country’s substantial oil and gas riches to build many monuments to himself; rebaptising one of the months after himself; and insisting that all schools study his works. He had died unexpectedly about six months before we arrived. Indeed, we feared at one point that we would not be able to go to Turkmenistan as after his death the country was “closed” pending presidential elections. Fortunately, the elections took place without trouble and one of his ex-Ministers has now replaced him.

The population hope that the new leader will moderate some of the absurdities of the previous regime, but during our trip the Turkmenbashi personality cult was still much in evidence. It may well suit the new man to hide behind Turkmenbashi for a while, and it seems that he is already making some small changes, for instance allowing internet cafés to open. At least there was a presidential election, even if all the candidates were from the same party, rather than a takeover by Turkmenbashi’s unpopular son. The latter is said in the bazaars to be under virtual house arrest, as he is supposed to have millions stashed away in foreign bank accounts and the government won’t let him leave the country until he reveals where these bank accounts are and returns the money.

The last British Ambassador here had the good sense to devote a large part of his time to writing an excellent guide-book to the country, published just before we left, and that was a godsend. Our guide in Turkmenistan, who told us that he was once stuck in a sandstorm with the aforesaid Ambassador, said that the latter spent his time criss-crossing the country and ended up by knowing it much better than any Turkmen.

Arrival: 20 May 2007

We arrived at Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, in the middle of the night. The airport was an impressive example of work creation. Many layers of officials stood between us and the exit, each determined to copy out our passport and other details into huge handwritten ledgers – although to do Turkmen modernisation justice, one official had an actual computer and entered our details on-screen. And as we queued between booths, acolytes checked to see that we were holding the right pieces of paper for the next set of officials. Ashgabat is also the only airport where anybody has bothered to X-ray my luggage on the way out. As we were on full tourist visas, we were obliged to have a guide throughout our time in Turkmenistan, and when we finally emerged on the other side of the barrier we were met by the amiable Jabbar, together with minibus and driver.

Talkuchka Market

Off to our hotel for a brief kip and then to the local Sunday Market at Talkuchka on the outskirts of the city. It was a huge affair spread over an immense area, but not up to Kashgar, according to my companions who were there last year. The livestock market, the best bit, was almost over by the time we arrived, but still fascinating – with sheep, goats, cows and camels. The sheep ranged from black Astrakhan lambs in their old-lady fur coats through to extraordinary fat-bottomed sheep, the huge lumps of fat on their rumps wobbling as they moved. This fat is much prized; we met it later as chunks on kebabs or chopped into tiny pieces in soups to give them body (it is soft like bone-marrow and really rather nice). There were also cashmere goats, but according to our guide virtually worthless as the government has decided that cashmere need not be exported as there is plenty of oil to earn foreign exchange.

Fat-bottomed sheep at Talkuchka market

The camels (dromedaries) had all been sold and were being dragged by their back legs, kicking and (literally) screaming, on to open-backed trucks, all on top of each other so the trucks were heaving masses of legs and necks. The purchasers were herdsmen in from the desert, most now wearing the global male attire of trainers, jeans and T-shirts, but a few still with the huge shaggy sheepskin hats and leather boots that were the traditional Turkmen costume.

Camel with herdsman at Talkuchka market

Camels on a lorry at Takulchka market

Merv and Gonur: 20-22 May 2007

Merv

After the market, we were packed back into our minibus and whisked off to Merv, founded by the Persian Achaemenid dynasty in about 500 BC and one of the great cities of the silk road from the 8th to the 13th century. But it was demolished with extreme thoroughness by Genghis Khan, and all that remains now are the lumpy remains of crumbling mud-brick walls, identical in colour to the surrounding desert, that we grew to know so well from our trips to similar ruined silk road cities in China. Merv was on the Oxus, still a large river that we crossed twice on our travels by somewhat alarming bridges – one was a railway bridge used by cars when there was no train, and the other a series of extraordinarily rickety pontoons that looked as though they would be born away by the slightest storm.

Looking out over the Oxus or Amu Darya

Merv’s latest incarnation is the boring modern city nearby called Mary, where we stayed in one of the country’s few family-run hotels. Called the Caravan Hotel, it was in a private house built round a courtyard – the same type of courtyard house that is standard from North Africa to China. The outer walls of such houses are built traditionally of unfired mud-brick, windowless and blind. One enters through a close-fitting wooden or metal door into a courtyard in which – at least during the summer months – all family life takes place. Some of the courtyards are huge and contain large kitchen gardens or even a few crops. Almost all contain at least a fruit tree or two and some greenery. As one enters from the noisy, parched and dusty street into the unexpected leafy calm, one understands why the Koran so often describes paradise in terms of gardens. Quite often (though not in our hotel), the animals are stabled along one side, with the family quarters and storage areas arranged around the other sides. In honour of its status as a hotel, in our building the owner had installed two shower-rooms with sit-down loos in what were probably the old storage areas. Given the uncertain plumbing, these were not places in which one was tempted to linger.

For dinner we made our way to an open air café in town where kebabs (which go by their Russian name of shashlik) were being grilled and had the first of what was to become our standard meal of shashlik, bread, tomato and cucumber, of which we grew thoroughly fed up (except perhaps for Jenny who is a dedicated carnivore). The shashlik could sometimes be varied with noodles or soup, always with a quotient of lumps of fatty and gristly meat, but we soon discovered that if we wanted vegetables, it was tomato and cucumber or nothing – I don’t think we had more than half a dozen meals with another vegetable during the entire five weeks. The shashliks were mainly lamb or beef, but pork was also available in both Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and seemingly freely eaten by most Muslims, a result of the long Russian dominance. Our 50-something driver in Uzbekistan described how young men doing their national service in the Soviet army were fed pork; on the first day they did not eat it; nor did they on the second day; but by the third all compunction had gone. Now only the “whitebeards” did not eat pork.

Beer is also freely available, and although Islam is now the official religion, it clearly sits extremely lightly on the average Turkmen. No doubt this is partly due to the determined anti-religious policies of the Soviet authorities. We were told that the President also shut down all the mini-madrassas (religious schools) that sprung up with foreign Islamic support after independence, fearful of nefarious influences. But I suspect that the Turkmens, being nomads, never really adopted the more authoritarian aspects of Islam. None of the women were remotely veiled. They are the Parisiennes of Central Asia, clad in extraordinarily elegant caftans in bright and attractive colours with braiding round the neck. In the villages, the caftans are loose with sleeves at least to the elbow, but in the towns they are tailored to show off the figure and in summer the sleeves are well above the elbow. Married women in the less sophisticated areas wear headscarfs, but tiny ones tied behind the head Russian-style – no nonsense here about not showing the neck and ears.

There are very few mosques, but a strong Sufic influence in the past has given the Sunni Turkmens a strange passion for shrines. The latter are usually based on the graves of holy men, around which handsome mausolea have been built. The shrines receive a steady stream of pilgrims and still show many signs of Zoroastrianism, the pre-Islamic religion in these parts. There is usually a sacred tree on which wish-rags are tied; childless women tie miniscule cloth cradles between two branches. Often, tiny constructions of three stones set in a triangle (representing the Zoroastrian trio of fire, earth and water) have been built by pilgrims on the ground next to the mausoleum. Our guide told us that a lamb is still sometimes sacrificed today when a person has a problem or a difficult decision, with friends and relations then being sensibly invited round to eat it afterwards. I asked to which God the sacrifice was made – Allah or some old Zoroastrian god. The answer was that people were somewhat vague about the precise identity of God; people thought in terms of “the way of God”.

Mausoleum of the Seljuk ruler, Ahmed Sanjar, built in 1157, near Merv

Mausoleum of Ahmad Sanjar, internal decoration

Sacred tree with wish-rags near Merv

Gonur

Not far from Merv, a much earlier bronze age site called Gonur has been excavated, and we were taken along a bumpy track to visit this site, not normally on the tourist itinerary, joining forces with a young diplomat from the German Embassy in Ashgabat and his American wife (gosh, her life sounded boring – coffee mornings and bridge). The archaeologist in charge, a Russianised Greek called Victor Sarianidi, has been working there since 1972 and is one of the grand old men of Central Asian archaeology (it was he who excavated the Afghan gold that we saw at the exhibition at the Musée Guimet in Paris last year). He was on site, looking the part with a magnificent leonine head, and we were sat down and given what was clearly the signal honour of being able to ask him questions. Jenny with her archaeological training was invaluable in keeping our end up; the young German diplomat was useless.

Front row: Victor Sarianidi and our guide Jabbar; back row: Kathryn on left, Sophia second from right.

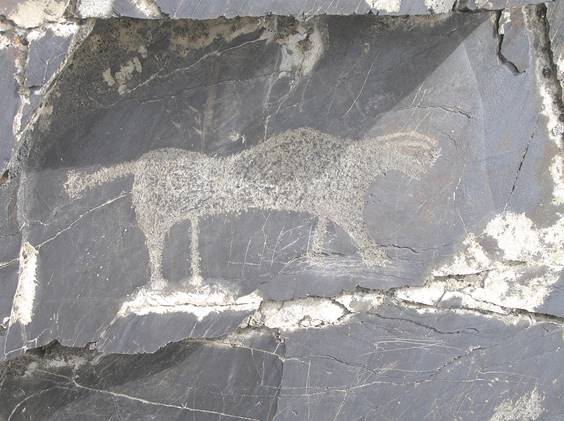

Gonur dates back to before 1,000 BC, and was abandoned when the local river changed course. It is a huge site, beautifully excavated. As in the later silk road cities, the buildings were built of sun-dried mud and straw bricks. Protecting the friable remains of these cities from the elements is a major challenge for the archaeologist, both here and in China. At Gonur, having uncovered the walls, the local archaeologists then plastered them over with a protective layer made of the same mud as the bricks, so one could still see the shape of the walls and the buildings – a good solution, even if it did not convey quite the same air of romance as the visibly crumbling ruins of the average silk road city. Lots of potsherds still littered the site, and every so often an amphora for storing grain had been left in the ground where it had been found. Where the main kiln had been, there were strange bits of glassy green rock where the heat had been enough to vitrify the stone all those years ago.

The site at Gonur

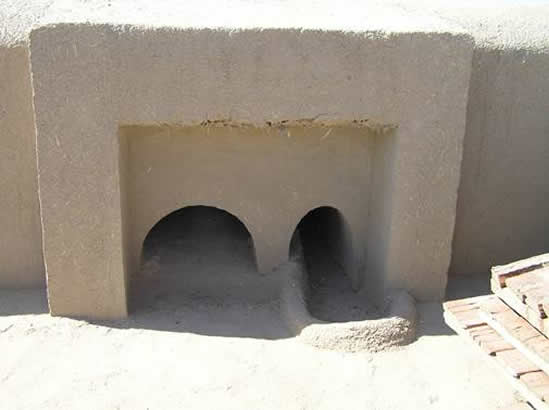

Victor Sarianidi had developed a fascinating theory that the religion of the inhabitants was proto-Zoroastrianism. The ruins contained strange double hearths apparently for fire sacrifices so that the lamb being sacrificed could be cooked without being adulterated by – or adulterating – the fire. This proto-Zoroastrianism also involved the concoction of a ritual drink, soma, the precise ingredients of which remain mysterious although clearly narcotic. Traces of soma were found on the site, and we were told that analysis revealed a potent mix of cannabis, poppy and ephedrine. Carvings and clay models found at the site show the dilated eyes of the consumers, and at one place near the main temple there were a series of coffin shaped compartments in the ground, possibly for the priests to sleep off the effects of the drug – they reminded me a bit of those drawer-like cubicles at Japanese station hotels in which drunken businessmen are put to spend the night while they sober up. We also saw some strange graves, belonging to a horse or donkey and three sheep, their skeletons still in situ. They had been buried ceremoniously with grave goods like VIPs – nobody knows why.

Proto-Zoroastrian double hearths at Gonur

Beds for stoned Zoroastrians to sleep off the effects of the sacred drug?

Serakhs: 22-23 May 2007

Our next stop, Serakhs, was a sleepy frontier town on the Iranian border not far from Mashshad. We had asked to go there to see the ruins of old Serakhs, an important silk road town between Nishapur and Merv whose heyday was in the 12th century under the Seljuk Turks. Because of its position, it is in a “closed zone” and all sorts of extra permissions had to be obtained to get us there. At the last moment it was discovered that our driver did not have the right permit and another driver had to be rustled up – altogether we had half a dozen different drivers during our week in Turkmenistan. The Turkmen driver who picked us up at the airport had been sacked by the next morning because of a spat with the guide, and replaced by the tall, dark and handsome half-Russian half-Central Asian Timur, the one who to our regret did not have the permit for Serakhs. He was replaced by a dour Turkmen called Murat, who was then replaced in Ashgabat by the aggressively blond Russian Volodya, who was joined for the trip across the Kara Kum desert by the equally Russian Sasha. Yet another Turkmen driver then took over for the drive to the Uzbek border, as neither of the Russians had the right permit for that border area.

All the main roads in the country (and also in Uzbekistan and Tadjikistan) have police/internal customs check-points at regular intervals, a legacy of Soviet times. Mostly these are staffed by bored uniformed youngsters who only occasionally stop a car or truck to relieve their boredom. But the check-point at the entry to the Serakhs area took us very seriously. Endless telephone calls were made to higher authority before we were finally allowed through as nobody wanted to take responsibility for the decision. The town itself is a dump of a place. It has a German colony sent here by Stalin during the Second World War and a large Iranian population – apparently the frontier was drawn through Serakhs province at a Moscow tea-party between the Shah and Stalin, leaving a lot of Iranians on the Soviet side who show no hurry today to return to black-chadored and alcohol-free Iran. A local Turkmen told us that the Germans were more friendly – “when four Turkmens and two Iranians meet for a meal, the Iranians speak Iranian”, whereas the Germans would speak Turkmen.

There are no hotels, so we were accommodated in the house of the head of the local archaeological mission. His house doubles as the headquarters of the dig was very basic, built around a big courtyard. We slept in two dormitory-type rooms normally used by people working on the dig, each with four truckle beds and not much else except a hideous chandelier ceiling light. Next door was room with a table where we were given our meals and which was the only place to sit when not in bed. On the far side of the courtyard there was a loo and a bathroom. The loo was an earth closet with a beautifully clean dried mud floor and two well polished planks to squat on. A small besom lay next to them, presumably to sweep away anything that missed the hole. The latter was an exceptionally wide one and immensely deep, and I was terrified that my money belt would slip off into it as I squatted. As we found elsewhere, the room itself was thankfully large and airy, so there was very little smell (far removed from those tiny stinking cubicles within which earth closets were confined in southern Mediterranean countries in the 1960s and 1970s).

The bathroom merited that name as it actually had a bath-tub in it. But as we were to find in a number of other places, including private houses, there was no plug and no sign that it was ever used for an actual bath. There was a non-working shower and a long sink-type tap protruding over the bath under which a small person like myself could squat to wash. This passion for unusable bath-tubs mystified me; it would surely be easier to have a simple shower with a drain in the floor, or a tap in the wall with a bucket and stool, as in India. The bathroom had a tiny sauna off it, presumably used by homesick Russian archaeologists in winter.

We were taken first to see the typical archaeologists’ room, full of boxes of shards and digging paraphernalia, to look at some of the finds (although the best have been whisked off to museums) and then to the site itself. The latter was only of moderate interest. Rather tantalisingly, they described but did not take us to their most recent excavations, full of Sassanian (Persian) and Zoroastrian remains.

Ashgabat, 23-24 May 2007

Back to the capital, Ashgabat, which we had yet to see properly. On the way, we stopped at a “fish restaurant”, a cafe by the road-side that served fish from a nearby reservoir. It was deep-fried and very dry, but surprisingly good with the ubiquitous tomato and cucumber and a most welcome interruption from the endless meat kebabs.

I had last been in Ashgabat in August 1966, when it was a dusty town of concrete five-storey Stalinist flats built following the earthquake that had destroyed the place in 1948 (Stalin is supposed to have decreed that no apartment blocks in the Soviet Union should have more than five floors, to avoid the need for lifts). It is now quite unrecognisable – the whole centre is a city of green trees and white marble palaces interspersed with fantastical monuments to the first President and his mother. The latter was killed in the 1948 earthquake and subsequently idealised and idolised by her orphan son.#

A view of Ashgabat in 2007

The palaces house ministries, museums and other official buildings and are mainly neo-classical in style, with huge pillared porticoes. The monuments range from the absurd to the really rather impressive. Into the first category falls the famous Neutrality Arch (to mark Turkmenistan’s “permanent neutrality”), topped by a small golden statue of Turkmenbashi. It is supposed to revolve so that he is always facing the sun – only unfortunately the mechanism has been going too slow or too fast and it is now out by a few hours.

The Arch of Neutrality in Ashgabat with the revolving golden statue of Turkmenbashi on top.

The most impressive monument was the “Earthquake Monument”, built in memory of the 1948 earthquake victims. Turkmen mythology has the earth perched between the horns of a bull; and when the bull moves his head to readjust his load, the result is an earthquake. The dark bronze monument shows a well-endowed bull holding the globe, rent with dramatic fissures out of one of which emerges a small golden boy – representing the child Turkmenbashi surviving the earthquake. This description makes it sound absurd, but it is well and powerfully sculpted.

The earthquake monument in Ashgabat with a golden baby Turkmenbashi emerging unharmed from the quake.

Our hotel was a little way from the centre, on a road down which Turkmenbashi used to drive in to work. He decided at some point that the city needed some more hotels and that this was a good place to put them. So one side of the street consists of a row of hotels, all in generous and well-planted grounds, so as not to be visible one from the other. Each hotel is different in theme and construction; ours was associated with the oil industry and had a “nodding donkey” in the middle of a flowerbed in front of the entrance. The vast atrium was full of marble pillars, grandiose mosaics and particularly vulgar chandeliers. When one looked closely, everything was very slightly tacky, with cheap plastic fittings already warped and broken. Needless to say, as there are so few visitors most of the hotels are empty for months at a time (we seemed to be the only guests in ours). On the other side of “Hotel Street”, blocks of splendiferous white marble flats have been built, but apparently so expensive to rent that they also are mostly empty. The road itself was immensely wide, with three or four lanes on either side, but so few cars that we could wander across with no problem. Indeed, the whole area was as empty as a ghost town.

The nodding donkey outside our hotel in Ashgabat

On the way out of town, old Stalinist blocks still survive and also some more traditional courtyard houses, sometimes incongruously combining a clay tamdyr oven outside or a camel in a stable with a satellite dish on the wall. This was not the only interesting clash of old and new. Neutrality Arch boasted an efficient modern German lift to take visitors up and down. When we pressed the button to summon it to go down, the door immediately opened to reveal a couple of disconsolate and somewhat jungly-looking Turkmen youths, clearly up from their village to see the bright lights. They had got into the lift and the doors had closed behind them, but they had probably never been in a lift before and had no idea which button to press to go down, so they had apparently been standing there patiently waiting for something to happen.

It is quite hard to tell how much of the oil-wealth has trickled down. On the one hand, little seems to have been spent on modernising for instance the health service (although there was no obvious poverty or disease). On the other hand, the main roads at any rate are excellent, and Turkmenbashi decreed that every household could have free gas and electricity (and it costs less than five dollars to fill a 65-litre tank with petrol). While this may prove a wasteful and short-sighted move in the longer term, it presumably must have helped many households in the short-term. There seemed little shortage of reasonably priced electrical equipment. Most houses had a satellite dish – indeed the fronts of some blocks of flats are so covered in them that they look like scales on a fish (we were told that Turkmen TV is so dreadful that everybody has a dish to tune into Russian or Turkish stations).

The main museum was in a huge new building complete with portico and vast be-fountained fore-terrace. The building was alive with uniformed officials and smartly dressed girl attendants, but we seemed to be the only visitors. The staff were bemused by us as they are clearly used only to organised groups, but they finally let us in. The cavernous ground floor is devoted to – guess what – the life and doings of Turkmenbashi. But the next floor has a well-displayed collection of finds from archaeological sites around the country, including Gonur and Serakhs. There are some beautiful things, including some stunning 2nd century BC ivory rhytons, purely hellenic in style.

The next day, at my instigation, we went with our guide to the carpet museum. Turkmen rugs – those busy red ones that we know as Bukhara rugs as that is where they used to be sold – are central to the local culture. The national flag has the carpet patterns from each of the five provinces; and one of new bank holidays proclaimed by Turkmenbashi is National Carpet Day (along with, inter alia, National Melon Day and Holiday of the Turkmen Horse). The museum was interesting. I had never really got my mind round the different patterns of Turkmen rugs and all became much clearer – although unfortunately most of the carpets on display were in hideous chemical dyes, to the disgust of Jabbar, our guide, who has started a business with an Afghan friend making carpets in naturally died wool and silk. The most hideous thing of all was “the largest carpet in the world” on a wall in a vast hangar on one side of the museum. Turkmen carpets, with their small repetitious patterns, are fine when small, but to be faced with a carpet of almost 200 square metres, all in harsh chemical colours, was just too much.

We are now Turkmen TV stars. A TV crew was standing aimlessly about as we went round the museum, and just as we were leaving plucked up the courage to ask to interview us – as we were again the only visitors, they must have been waiting around all morning for somebody to film. It turned out that National Carpet Day was in a few days’ time and was to be marked by an International Carpet Congress in Ashgabat, and the TV crew had been instructed to make a programme for it. As I was the one who knew most about carpets, I was pushed by Jenny and Kathryn before the camera and was interviewed for what seemed to be about 10 minutes, with Jabbar acting as interpreter (and prodding me to put in a plug for natural dyes, which I was only to happy to do). I drew on all my Diplomatic Service background to spout high-sounding stuff about the beauty of Turkmen carpets, the British 100-year love story with them, the marvellousness of the museum, the wonders of modern Turkmenistan etc (the British Embassy would have been proud of me). Jenny and Kathryn, who thought that they had escaped, then found the microphone shoved under their noses and had to find yet more things to say, albeit at less length. I then had to do yet another interview, this time for Turkmen radio, so they certainly got their money’s worth from us. I suspect that it was lucky for them to find some foreign tourists to interview, as tourists are few and far between in this country. Jabbar subsequently told us that his wife had subsequently seen us on telly and had been boasting to all her acquaintances about meeting us.

Jabbar was an interesting guy. His grandfather had been a big man in the Eastern Ersari province of the country, with “three flocks”, each of some thousand sheep and goats, who dominated a large local area with the help of a small private army (not dissimilar, no doubt, to the mini-war-lords still active in North West Pakistan and Afghanistan). The private army was no match, however, for the Soviet forces when they arrived to collectivise the herders of that area. After three members of the family had been killed, Jabbar’s father and grandfather saw the writing on the wall and fled to Afghanistan where there was already a big Turkmen minority. Jabbar was brought up there and trained as a doctor, subsequently going to work in Pakistan. When Turkmenistan became independent, he was one of quite a number of long-exiled Turkmens in Afghanistan and Pakistan who returned to their homeland. He came initially to run a charity organised village health project. While on this project, he met and married his wife, another doctor on the same project whose family came from the Turkmen shore of the Caspian. Apparently his many brothers have mostly married Afghans or other foreigners and it was a cause of touching delight to his mother that he had married “one of our people”. His mother, now 92 and widowed, remains exiled in Afghanistan – the Turkmen area of that country is peaceful – and says she will only return if she can travel by camel.

Jabbar’s wife is still doctoring, but he explained that he decided that he could not make enough money as a doctor and had given it up to become a freelance guide and interpreter – a sad reflection of the low pay and low status of doctors in the ex-Soviet Union. From our point of view, it was a great bonus to have a guide who could see Turkmenistan to some extent with an outsider’s eyes while at the same time having a lot more knowledge (from the health project) of Turkmen village life than probably the average urban Turkmen.

On our last evening in Ashgabat, Jabbar invited us to dinner at his flat, one of the few really good meals that we had during our trip. The flat was in a rather crumbly old Stalinist block in a suburb, but the suburb was leafy and inside everything was spic and span if rather small, with an array of electronic equipment. After removing our shoes, we were shown into the living room, where a cloth had been spread on the floor and laid with sweetmeats – raisins, sultanas, nuts and lumps of sugar in little dishes. We were to discover that, throughout the region, this spread is automatically brought out when guests arrive in even the meanest village house or yurt. We sat round on the floor in varying degrees of discomfort and were served fried sturgeon from the Caspian sent by Jabbar’s wife’s family, with an excellent herb and yoghurt sauce; a magnificent plov with some Afghan touches; and the usual salads. The couple’s two young sons (13 and 9) joined us somewhat shyly and reluctantly, and we disgraced ourselves by not knowing about the latest Western pop groups. They go to a private Turkish school, set up with money from the Turkish government after independence, where the education is apparently a lot better than in the Turkmen schools, not least because less of the curriculum is devoted to Turkmenbashi’s great work Ruhnama: Reflections on the Spiritual Values of the Turkmen. They are clearly intelligent and we were told that they are at or near the top of various nationwide school league tables.

We sang for our supper by viewing the amateurish English-language video that Jabbar had made to promote his natural-dye carpet business and offering tactful criticisms and suggestions. Rather embarrassingly (as we were not in buying mode), earlier in the day he had taken us to see the business, in a house on the outskirts of the city, with a yurt (i.e. nomad tent) in the courtyard. We were offered tea in the yurt, which was furnished with a large television set, turned on in our honour to some Russian-language news programme as soon as we entered. Large numbers of rugs were then spread out on the ground before us, mostly not terribly attractive (the ones destined for the Russian market were in particularly garish colours), and all very expensive. We excused ourselves by explaining that for weight reasons we had sworn not to buy any rugs until the end of our trip.

The Kara Kum desert and the flaming crater, 24-25 May 2007

Kara Kum

Crossing the desert to the other end of the country proved quite a business. There are some 400-500 kilometres without petrol and we were told that we needed a back-up vehicle. So two minibuses were mobilised, each with its Russian driver (there are still quite a few Russians living and working here), to take the three of us and Jabbar. We were taken to wait at the flat of one of the Russians while supplies were purchased, another decrepit apartment block in a leafy suburb, in an area obviously favoured by the Russian community. Interestingly, the bathroom in the flat was well up to Western standards, with plugs in the bath and basin; unlike the other bathrooms that we met in this country we did not feel that if we leant too hard on any of the fixtures they would immediately fall off. So it appears that there is an interesting cultural divide over the importance and standard of bathrooms. Turkmen hotel-builders, it seems, are interested only in making the bathrooms looked like Western ones; whether they work is a secondary consideration.

The road through the desert began as a four-lane motorway, but soon turned into a single carriageway. All along, however, it was pretty good and parts of it were being rebuilt to a high standard. Every so often there were grotty little concrete canopies by the roadside that we decided were bus shelters, although we hardly saw any buses; indeed there was little traffic apart from occasional lorries. Probably this road follows fairly close to the one taken by the silk road caravans.

The road through the Kara Kum desert

Kara Kum means “black sands”, but the sand that we saw was mainly sand-coloured. The first part of the desert consisted of low dunes with lots of scrub (mainly tamarisk and saxaul), affording pasture only for a very few scattered goats and camels. The camels are all dromedaries. This used to be Bactrian territory, but dromedaries were introduced by the Arabs and displaced the Bactrians, as dromedaries are really better suited to this sort of flattish desert country. The Turkmens complain that in exchange for the dromedary the Arabs took the horse, an infinitely superior creature (the Turkmens, legendary horsemen, retain a mystical feeling for the horse, although we saw very few while we were there). Unfortunately, we were just too late to see the spring blooming of the desert, but there were still some attractive flowering bushes.

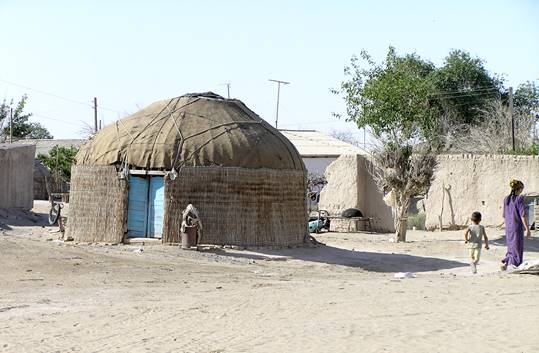

We passed a couple of villages and stopped to wander round one. A collection of mean one-storey brick boxes with tiny windows and the occasional yurt, all built on dusty sand, it was hardly prepossessing. Yet if one looked closely, most of the houses had electricity and TV aerials. We were given fermented mare’s milk from one of the houses – it was tangy and refreshing and slightly fizzy, and came diluted with water so cold that it must have been in a fridge. We were told that the yurts were used by the inhabitants of the houses as extra rooms, especially in spring and autumn when the elements are not too extreme (so much for the fabled climatic suitability of yurts). We also visited the village store, which had a reasonable supply of basic foodstuffs.

Village in the Kara Kum desert, with a yurt being used as an extra room

The village still lives partly from herding. The shepherds operate as teams, three men taking the entire village flock off to pasture, sometimes up to 50 km away; these three live with the flock and are then relieved by another three every week or so. They travel on little motor-bikes and now part of a shepherd’s trade is to know how to repair any motor-bike. Most of the men in the village, however, work for the government, on the roads or on other building work. The women for their part look after the animals in the village, milk the camels and make the felt rugs that are used as flooring in the houses and yurts. We saw two women at work on a rug, and very hard work it was too. The wool needs to be compressed into felt, which is done by rolling and unrolling the rugs hundreds of times on a sort of stone table, pressing on them hard the while with the fore-arms. Some coloured wool is used to give the rugs an attractive decoration and they are apparently very hard-wearing, lasting in the houses for up to 20 years.

Camel being milked from both sides

Village women rolling felt

The end product

The flaming crater This is an area where there are traces of oil and gas, and we drove off the road to look at a couple of craters with evidence of geological activity. Both were drum-shaped, some 30 metres across and about the same deep. The bottom of the first was filled with evil-looking black water, just stirring as bubbles rose slowly from the depths. The second had fiercely boiling mud. The rims of both were quite crumbly, and it was with some unease that I approached close enough to the edge to peer into the depths. They were the sort of thing into which one would definitely not wish to fall, with their sheer unclimbable sides and uninviting stew at the bottom.

Better was to come. We stopped to camp for the night (we had brought tents with us) at yet a third crater, seven kilometres off the road along a tricky track across a large sand dune. This crater was one of the most impressive and extraordinary sights that I have ever seen. Bigger than the others, it was some 60 metres across and again drum-shaped with sheer sides going down 20 metres or more. The whole bottom of the crater and most of the way up the sides was alight with bright orange flames, fed by gas seeping from the rocks – very attractive licking flames reminiscent of depictions of hell in medieval representations of the Last Judgement. This crater apparently resulted from an explosion caused by Soviet oil exploration in the 1980s, and has been burning ever since. The impression created by the elemental force of the fire is difficult to convey satisfactorily. It had a permanent roaring sound and our guide-book described it as like a thousand bunsen burners; to me, as I never did science at school, it was like a gigantic gas-ring. At night it attracted thousands of insects, and they in turn attracted owls, whose undersides were lit up orange by the flames as they flew above us.

The flaming crater when we arrived as dusk was falling

The flaming crater in the morning with our vehicles and tent in the foreground

We camped in the desert about a hundred metres from the crater, so the roaring lulled us to sleep. We had a local felt rug in our tent and it was extraordinarily comfortable; the ground was rough and stony ground, but I hardly felt it. During the night, one of the many picturesque black beetles that patrol the desert got into our tent and could not get out (the tent was the sort with an integral ground-sheet). We could just hear the very faint rustle of its tread as it went round and round, but both Kathryn and I were too sleepy to do anything about it (Jenny had taken her sleeping-bag outside to commune with nature and avoid our snores).

For dinner, the Russians – one of whom apparently used to be a cook – went off into the desert to collect saxaul wood to build a fire and produced an excellent well-marinated lamb shashlik – the best we had during our trip, although with some bits so tough that I had to conceal them in my pocket for later burial in the desert. The Russians had also brought vodka and there was much merriment all round despite the linguistic challenges – they had no English, so if Jabbar was not there to translate, we were reliant on my very rusty Russian.

Even though all adult Turkmens still speak (and read and write) Russian, one of Turkmenbashi’s aims seems to have been to obliterate all Russian traces. There are now virtually no signs in Russian or Cyrillic. Turkmen was originally written in Arabic script, then after the Russian revolution the Roman script was used for a few years, until Stalin decided that all languages in the Soviet Union should be written in Cyrillic. Turkmenbashi has now switched them back to a slightly idiosyncratic version of the Roman alphabet – basically that used for Turkish with a few twiddles of his own devising. Turkish and Turkmen are so close as to be mutually intelligible, so the change makes a lot of sense. But it has meant that some unfortunate elderly Turkmens have lived through four changes of script.

Konye Urgench and Dashoguz, 25-27 May

Konye-Urgench

The next morning we completed our crossing of the desert. This eastern part is very dull, dust, stone and almost no vegetation. Our destination was Konye-Urgench near the Oxus, for long the capital of the romantically named kingdom of Khoresm, and in the 11th century one of the great Islamic centres of learning. Both the Mongols and Tamerlane had a go at it. But it was rebuilt several times and amazingly quite a few monuments survive, in particular a group of 14-16th century tiled mausolea of holy men. There were quite a few Turkmen visitors while we were there, but no Westerners. Visitors are supposed to circle each mausoleum or the tomb within it, and then say prayers. In each of the bigger mausolea a man had constituted himself as an official prayer leader, and after doing their circuits the visitors sat down with him to chant their prayers – prayers which only seemed to be validated once a note had changed hands. Our guide, who was strongly anti-clerical, claimed that the prayer-leaders were not above telling the visitors that they only needed to make one circuit so as to increase throughput and profits.

Mausolea of Najm ad-Din al-Kubra (founder of a Sufi order),14th century; and Ali Sultan (16th century local ruler)

Front of a 14th century mausoleum at Konye Urgench, with pilgrims. Note the elegant kaftans of the women

12th century mausoleum of Il Arslan, ruler of Khoresm 1156-72, Konye Urgench

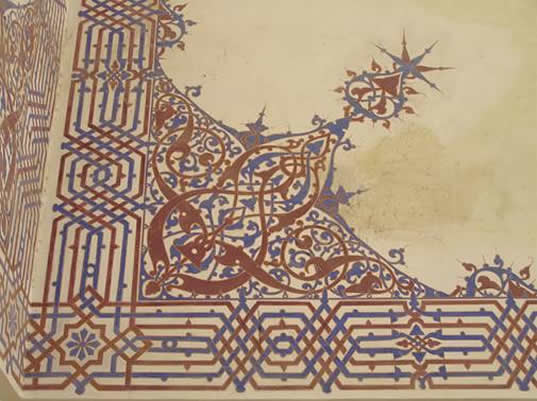

The tile-work of these mausolea is extraordinarily fine. The tiles on the inner dome of one, the mausoleum of Turabeg Khanum, were one of the best things that we saw, rivalling Bukhara and Samarkand, by virtue of both their beauty and the geometrical wizardry of their pattern. The background colour was dark blue, giving a night sky effect. 365 interlocking shapes are traced on the blue by a single line, criss-crossing and wandering around the dome and somehow achieving symmetry or near symmetry. The calendar motif was carried through to the building itself which had a row of 12 arches for the months and 24 smaller arches above for the hours.

The inside of the dome of the mausoleum of Turabeg Khanum

Tile panel in mausoleum of Najm ad-Din al-Kubra

Dashoguz

Dashoguz (formerly Tashaus), the main town in this area, is a dump and our hotel, probably the best in town, was pretty awful. It did, however, have functioning air conditioning (it was by this time nearly 40 degrees); running water; and, miraculously, an internet centre where I picked up my emails. We had an afternoon to spare, so we decided to walk the couple of kilometres into the centre to inspect the local (modern) monuments, said to include some fetching statues of dinosaurs, and the central market. Poor Jabbar gamely said he would come with us – to his regret, as the two kilometres turned out to be four along an exceptionally boring main road; the dinosaurs had been replaced by an ugly Caro-type piece of rusting ironwork; and the central market was closed, even though it was barely 5 pm (“Soviet hours” was our guide’s caustic comment). Dinner was equally disastrous, tough kebabs in a restaurant that cultivated Stygian gloom to such an extent that one could barely make out what one was eating.

Taxis here are interesting. There are many official taxis cruising the streets. But all private cars are also potential taxis. So one stands by the side of the road with one’s hand out and in no time at all a private car draws up, everybody being keen to earn a little extra by giving lifts.

The main hazards of the streets here and in most of the towns we visited were the open drains or conduits that run along most main roads between pavement and carriageway. They are often a couple of feet deep and two or three feet wide, usually with water running through them. They cannot be storm drains as there are no storms. And the water looked too clean to be sewage, so their role was not clear, unless they are for irrigation of the gardens in the courtyards of the houses. But stepping or jumping across them whenever one wanted to cross the road required quite a lot of care, especially at night. In the countryside, wherever there were crops, there were numerous irrigation channels or ditches, often with small boys (and sometimes quite large ones) bathing in them naked. As we drove past, any naked or half-naked boys resting on the banks would jump into the ditches like so many frogs jumping into a pond.

Zamakhshar

On our last evening, we drove out along unmade roads to see the nearby ruined fortress-city of Zamakhshar, immensely romantic in the evening light. A young Turkmen couple were the only other visitors as we clambered over the crumbling mud walls. The whole interior of the fortress was littered with potsherds and human bones – I found a skull under a bush – apparently untouched since the fort was stormed and the inhabitants massacred in the late Middle Ages. It is extraordinary to think what may still be buried under these ruined fortresses.

Potsherds littering a silk road city

*************************

Bread-seller in Bukhara Into Uzbekistan: 27 May 2007

The next morning we were driven to the nearby Uzbek frontier, where our Turkmen guide was due to leave us. The travel agent had arranged for a car and driver to pick us up on the other side, but for the actual frontier crossing we were on our own. I think we all had images of ourselves stranded on the other side in the middle of nowhere if the driver failed to materialise.

The Turkmen side of the frontier had queues of people waiting to pass, almost everybody wheeling one or more several large fridges or TV sets on trolleys. Some had as many as half a dozen, all still in their packing cases. Goodness knows what strange quirk in the taxation or economic regulations of the two countries was stimulating this traffic. Our guide quickly hustled us to the front of the queue, to our mingled guilt and relief. But even so the whole process still took about an hour and a half, and was all the more ridiculous as in Soviet times there was no frontier at all bar a simple check-point.

After interminable form-filling in duplicate for first passport control and then customs, and much writing into ledgers by officials, we cleared the Turkmen side. There was then a kilometre of no-man’s-land to cross to get to the Uzbek frontier post. A little minibus taxi plied its trade across the no-man’s-land. It was waiting empty when we emerged from the Turkmen controls, so we got in and sat down on three of the five seats. Within minutes a crowd of locals irrupted, mostly fat old women, and piled in, sitting on the floor, on the remaining seats and on top of each other and me (Kathryn and Jenny had been ushered into the exclusive front seats, so were relatively unaffected by this pile of humanity). Then the same tedious procedures on the Uzbek side, and a final 100-metre stretch to walk with our baggage (very High Noon) to get to the final barrier, never quite knowing if yet another official might suddenly emerge and turn us back. On the other side, greatly to our relief, the Uzbek driver who was to stay with us for the next fortnight was waiting with a very smart minibus (we opted for a driver and no guide in Uzbekistan). Uzbekistan is only a little smaller than Turkmenistan in terms of area and size of economy (based on cotton and some limited mineral wealth), but has five times the population, so its annual per capita income is a fraction of that of Turkmenistan. However, to a superficial tourist eye, it appeared as developed if not more so than Turkmenistan. One exception was petrol stations. Whereas Turkmenistan (outside the Kara Kum desert) was full of petrol stations, albeit primitive ones with old-fashioned pumps with dials, they were much less frequent in Uzbekistan and seemed quite often to have run out of fuel.

Uzbek women are noticeably less elegant than their Turkmen counterparts, often very fat and clad in a mismatched mixture of eastern and western clothing. In the countryside, the main garb is long flowing dresses in hideous loud floral prints, sometimes with trousers underneath like a salwar-kameez. But otherwise habits, buildings and food seemed very similar. There was, for instance, a clay tamdyr bread-oven outside almost every village house. Tamdyrs seem to have a certain mystical significance, and even brand new houses have a tamdyr built outside them.

Tamdyr oven, Uzbekistan

Linguistically and alphabetically, Uzbekistan is in a mess. There are more Russians here than in Turkmenistan and most notices are still in Russian as well as Uzbek. As in Turkmenistan, in Soviet times Uzbek (also a Turkic language) used the Cyrillic alphabet; and again like Turkmenistan, after independence in 1991 it switched to the Roman alphabet. But infuriatingly (as Turkmen and Uzbek are very similar and an alphabetic common market would seem to be an obvious advantage), they opted for different spelling conventions (they do not use Turkish-style cedillas or umlauts, for instance, and also use different vowels – non for nan, for instance, on the grounds that this is more phonetic). Just to complicate matters further, five years later, they slightly changed the spelling conventions that they had just adopted. Not surprisingly, a lot of people seem to have decided that it is simpler to stick to Cyrillic, especially as it is still used for Russian. So notices often come in three versions: Uzbek in Roman script; Uzbek in Cyrillic script; and Russian, again of course in Cyrillic.

The desert fortresses and the Ayas Kala yurt camp, 27-29 May 2007

The border between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan runs roughly along the Oxus, so we had now entered Transoxiana. The next couple of days were spent going round the many ruined fortresses on the old flood plain of the Oxus east of Konye Urgench. Apparently an Italian archaeologist took a little plane up and counted no fewer than 63, most of which flourished some time between 500 BC and 800 AD when this now arid area was a fertile marshland. The fortresses vary greatly in size. All were surrounded by defensive walls and most originally had a palace or fortified building on one side. There was then an area for the hoi polloi and for bringing in animals in time of danger. All were built of mud-brick identical in colour to the surrounding soil and are now in a ruinous state. In some the outer walls are crumbly but largely intact and the site of the palace inside can be discerned. In others, only odd bits of external wall are left, sticking up like a few rotten tooth-stumps left in an edentulous mouth.

The walls of one of the many other ruined fortress cities in Transoxian a near Ayas Kala. Like an edentulous mouth.

Another, this time by an oasis and therefore near habitation

We saw only about half a dozen of the 63 fortresses. As all look fairly similar, our driver obviously thought we were barmy to want to see even that many. When it came to the last one on our list, he claimed that there was no road to it. But we spotted the fortress across some fields and made him stop so that we could walk to it – forcing our way as we went over various hedges, irrigation canals and crops. By the time we were ready to go back to the minibus, the driver, shamed by our enterprise, had found a small boy who had told him how to drive up to the fort, so we found him outside waiting. After that, he obviously realised that we wanted to see everything we could, and really threw himself into the spirit of things, seeking out every last pile of ancient bricks for us.

Crumbling mud-brick desert fortress

The history of this area is incredibly complicated and I cannot even begin to summarise it. The area has always been entirely dependent on efficient irrigation systems drawing on the Oxus, and the downfall of most of the fortresses was due either to war or to changes in the course of the river destroying or disrupting the local irrigation arrangements. Only one, the largest, Toprak Kala, had been properly excavated, so that one could see the outlines of rooms and houses. No doubt all sorts of yet to be discovered treasures still lie beneath the other forts. All were romantic to climb over, especially as we were usually the only visitors (only two are regularly visited by the groups). But every time the winter rains come, and alas every time a visitor climbs over a piece of wall, yet more crumbles away. So we were very conscious of being probably the last generation who would have such extraordinary access. The walls are favourite nesting places for birds, and are pock-marked with nesting holes. In one larger fortress water had collected to form a swampy area in the middle that was a real birdie’s paradise. In particular, there was a flock of about a hundred bee-eaters wheeling round and coming to rest on the ground only some 30 metres from us – a magical sight.

Bee-eaters

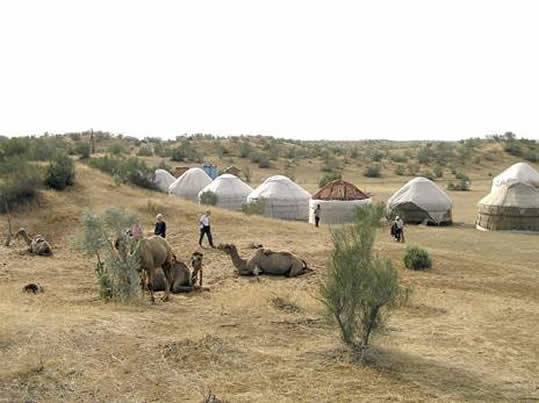

Our accommodation was a yurt camp established by an enterprising Kazak family in the desert by the ruins of a 3rd-4th century fortress. When our travel agent in London said that she had arranged for us to stay in a yurt, I naively imagined a real village of yurts inhabited by locals, although I did begin to wonder when she mentioned chemical toilets, hardly echt. What we found was a dozen yurts artificially and surreally planted in the middle of nowhere (or rather below one of the ruined desert fortresses), designed specifically for tourists, with all supplies brought in from many miles away and a group of bored-looking camels for any tourists who fancied a camel-ride. This was the first place that we had been to where all the locals present were there only to service foreign tourists.

The Ayas Kala yurt camp in the middle of the desert, over-looked by a ruined silk road fortress. Note how the skirts of the yurts can be hitched up to create a draft.

One yurt served as a dining-room, and each of the others slept up to five people on pretty comfortable futon-type beds. The yurts were round, with a wooden frame covered by felt and/or canvas. The bottom of the covering could be hitched up to allow the air to flow in most pleasantly when it was hot. The three of us shared a yurt and it took us some time to master the hitching up of the ventilating skirt; on the first night, when there was a dust storm, the result of our efforts was to give Jenny plenty of air as she wanted but to leave Kathryn and me (especially me) in a howling gale. A brick-built central block housed kitchen and stores, and there were showers and chemical toilets in blocks on the edge of the camp. There was also a generator providing electricity during the evening (one tiny light-bulb per yurt), but it was switched off at night. The food was adequate but pretty awful, and the whole place was run with a rod of iron by a Kazakh lady, who would rush up and say “Madaaaame” loudly and reproachfully every time one committed a solecism like going into a yurt without first removing one’s shoes or not finishing one’s soup.

The camp seems to have become part of a well-established tourist circuit that takes in Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva; every night during the season there is a tour group staying there. There was a German group when we first arrived, who were just leaving, to be replaced within hours by a French group. In the evening, Uzbek musicians were imported to entertain the group (and perforce us) and one of the female staff quickly dressed in some sparkly robes and transformed herself into an exotic dancer. “Madame” implacably dragged every reluctant tourist in to join the dance, but she met her match in us; we were so irritated by her that we refused to budge.

The best thing about the yurt camp was being able to wander at will up into the ruins and out into the surrounding desert. On the first evening we wandered up to the fortress as the sun was setting, to the irritation of a Russian film crew from Moscow who kept trying to chase us away – although, typically of film crews the world over, there was no sign of their actually doing any filming. And on the second evening we walked a couple of kilometres through the desert to a nearby lake with quite a lot of bird-life.

As so often, the desert proved fascinating when examined at close range. Fauna included lizards, snakes, beetles and sisliks (ground squirrels), each leaving a different trail in the sand. There was one animal that left large brushing tracks at intervals of 2-3 feet that puzzled us considerably until we realised that it was in fact the dead leaves of a certain plant that had become detached and were being blown around like tumbleweed. We then argued endlessly about whether the leaves were associated with some spectacular large dried flower-heads, up to 4 foot tall and looking like giant alliums or multi-armed windmills, that appeared at intervals in the same area but not obviously from the plants from which our dried leaves had come. As we subsequently ascertained, they almost certainly were from a later stage in the life of the same plant, the pale ferula, an umbellifera of the asafoetida-producing family that produces only leaves for its first three or four years.

Khiva, 29 May-1 June 2007

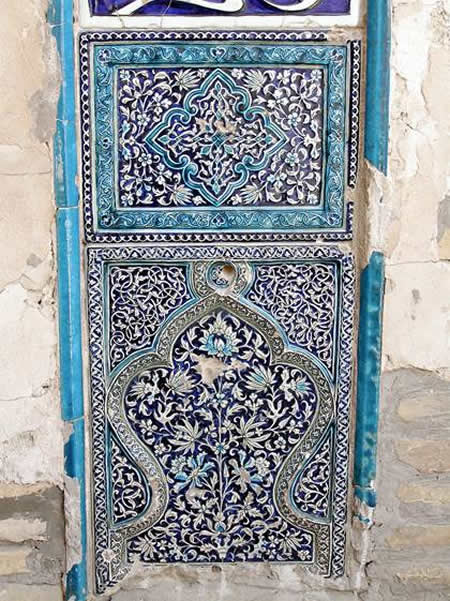

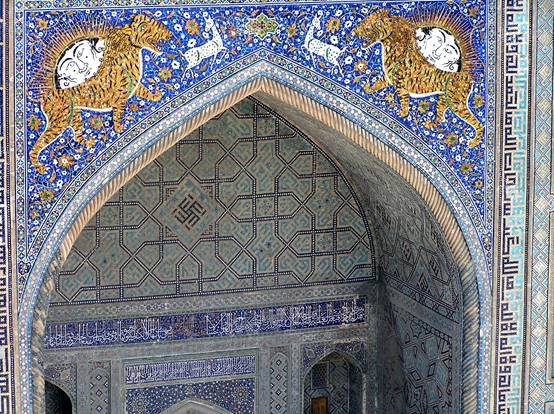

Our next stop was the town of Khiva, the ancient capital of Khoresm and the third most visited site in Uzbekistan after Samarkand and Bukhara. The walls of the city are said to have been laid out by Shem, son of Noah, and it was first mentioned in Arab manuscripts in the 10th century. But it only really became important in the 16th century when it was taken over by the Uzbeks and began replacing the dying Konya Urgench in nearby Turkmenistan (the latter had never really recovered after Tamerlane ordered its destruction in 1388). Khiva seems to have been largely the abode of robber barons until the end of the 18th century, when, for reasons that remained unclear to us, the contemporary Emir of Khiva had a fit of religion and decided to embark on a religious building spree, embellishing his capital with quantities of madrassas and palaces in the 15-16th century Timurid style, ablaze with blue and turquoise tiles.

View of Khiva

Outside the walls of Khiva

The small inner city still has its walls virtually intact and was turned by the Soviet authorities into a large-scale museum. Most of the inhabitants were moved beyond the walls and everything tidied up, so the whole place has an unnaturally swept and polished look, with not a piece of litter in sight. A single unhappy-looking camel is permanently tethered in the main square, apparently to add local colour. Some of the guide-books are scathing about the effect, and the whole place was indeed rather dead. Every single shop was for tourists, and one even had to buy an entry ticket if one entered by the main West gate. But some locals are creeping back in, and one has only to go out of the city’s Eastern gate to be in a full-scale oriental bazaar. And there is no doubt that the walled inner city is a magnificent ensemble, given the high density of historic monuments within such a tiny area (no more than 800m by 600m if that).

A view in Khiva – a UNESCO-polished city.

The individual monuments are also magnificent so long as one does not examine the tile-work too closely. The tiles are nowhere near as accomplished in either technique or design as the earlier (15-16th century) Timurid ones in Samarkand and Bukhara, the patterns too busy and the colours sometimes ill-assorted. Most of the monuments had been fully restored (or indeed over-restored), but there were a few on which work was still in progress. We poked our heads through the door of one, and found ourselves invited by workmen into what was once a spacious harem, with iwans (arcades) and courtyards. We were also determined to find the “Kheivak” well that according to our guide-book was the original spring that attracted desert caravans and early settlers to the city and gave it its name. After some wandering round the otherwise uninteresting part of town in which the well was said to be, an old woman guessed what we were searching for and led us to a private courtyard where the now dry well lies. It was not very interesting, but we felt the usual satisfaction at having successfully sought out an unobvious sight.

Part of a tiled palace in Khiva

Tilework in Khiva – not to be looked at too closely.

The main caravanserai of the town, a huge multi-domed building, has been turned into a covered market selling knick-knacks, jewellery and clothes. One wanders into what looks like a wonderland of sparkling treasures until one looks closely and notices the shoddy quality of everything on sale. The caravanserai led into an enormous high-roofed hangar that is the local “Department Store” – i.e. it sells furniture as well as clothes and sweets. And from there we emerged into the sunlight of a vast open market selling everything from food to automobile parts. Jenny and I had lunch at one of the kebab stalls, sitting at rickety tables. Jenny rather daringly poured onto her tomato and cucumber a most evil-looking concoction of cloudy liquid sitting in a dirty bottle on the table. The fruit and vegetable market had only a meagre choice – the only vegetables on display were carrots, onions, cabbages, tomatoes, cucumbers and potatoes – going some way to explaining the lack of choice in restaurants.

The best building in Khiva was the old Friday Mosque, bits of which date back to the 10th century. No tiles, but a forest of carved wooden columns reminiscent of Cordoba. It is now a museum, but there are so few tourists that it seems deserted and silent except for the cooing of doves and the low chit-chat of the women selling postcards and knick-knacks by the door. And it was a relief to have a cool stone floor rather than the carpets smelling of the toe-fug of a working mosque. Outside it was extremely hot, over 100º Fahrenheit, and I spent a pleasant hour sitting in the cool of the mosque one afternoon writing this diary while the others were languishing on a bed of sickness, having been poisoned by a chorba (meat soup) in a really nasty restaurant (the food in Khiva was particularly horrible).

Friday Mosque in Khiva

Friday Mosque Khiva – detail of column

Like most of the major sites in Central Asia, Khiva is a World Heritage Site and has clearly received quite a lot of international money. UNESCO-sponsored projects to revive traditional local crafts were much in evidence, with the old students’ rooms round the courtyards of madrassas transformed into workshops in which girls were hard at work at looms and knotting carpets and boys at wood-carving. The products were on sale outside at prices much above the locally prevailing rate for such things, although though still fantastic value for us. I bought two extremely pretty ikat silk scarfs for $10 and $15 (dollars were accepted everywhere).

Our hotel was a Soviet-era one that had had a thorough makeover, so it was modern and comfortable. Even the bathrooms were not too eccentric and enormously luxurious after the facilities at the yurt camp. Our driver was staying at a somewhat less comfortable hotel nearby, and complained bitterly about the boredom of having to stay three days in Khiva, whose people he despised (he is from Samarkand, which is a big city compared to Khiva) and about the awfulness of the food. Our hotel was about 200 yards outside the north gate of the city. The road from the hotel up to the gate was lined with flowerbeds in which a crop of wheat had been planted. On our last day, a large group of women descended with tiny scythes – really no more than hooks – to cut the wheat, which was then carted off in a lorry. One up to the municipality of Khiva for productive use of public space. Khiva for productive use of public space.

Women harvesting wheat in municipal flower-bed, Khiva

As we found elsewhere, even in Samarkand and Bukhara, we were almost the only independent tourists here, although there were a number of groups. Almost all the groups we saw on our travels were French; we met only one British group on our entire trip and after the French the next most frequent were Italians. We speculated endlessly about why the French are such keen central Asian travellers, but reached a clear conclusion. Perhaps they are now generally the most enterprising travellers of Europe.

The smarter coaches in this country, including those carrying tourist groups around, all seem to be second-hand imports from Europe, especially France. Often, the new Uzbek owners have not even bothered to repaint them, so they still have the logos of their previous owners. It is somewhat bizarre to see in the middle of Central Asia coaches inscribed with names like Voyages Denis Dieppe; Cars de Cornouailles; Transports Basques Associés; Etablissements Charpentier; or L. Garcia Torrelavega, and for a fleeting moment I wondered if these had enterprisingly brought their tourists all the way overland from Dieppe or the Basque country.

Bukhara, 1-5 June

The itinerary provided by our travel agent said “Today is a long drive across the Kyzyl Kum Desert. Make sure you take plenty of water with you and something to eat as the very few places where you could stop along the way are not very clean”. In fact, the 460 km journey was a pretty easy one (not more than 5-6 hours along goodish roads), with lots of scenic lay-bys next to the Oxus for photo-stops by the tour buses. Our driver took us to an admirable wayside restaurant (called Mehriobod near Gusli), where we sat on a terrace and ate the most delicious wild boar kebabs, together with the ubiquitous cucumber and tomato; the local version of ayran or lassi and a good curd cheese dip. The wild boar is apparently shot in the surrounding desert – the lady of the restaurant made shooting gestures to explain what we were getting. Our driver turned out to be a true foodie. He revealed during the meal that his family owns a restaurant in Samarkand where his wife is a cook. He then proceeded to regale us with detailed descriptions of the dishes that she cooked and how they were prepared (this was all in Russian – fortunately food terms are the thing I always remember best in any language).

Eating wild boar kebabs with our driver on the road to Bukhara

Bukhara was one of the places that I visited when I was here in 1966. It was then, as it was on this trip, by far the most appealing of the major sites. The old city is much bigger than Khiva, but like it all of a piece. Unlike Khiva, it is very much lived in and flourishing. The mud-brick and turquoise tiled monuments are less flashy than those of Samarkand, the tiling a lot more elegant and discreet.

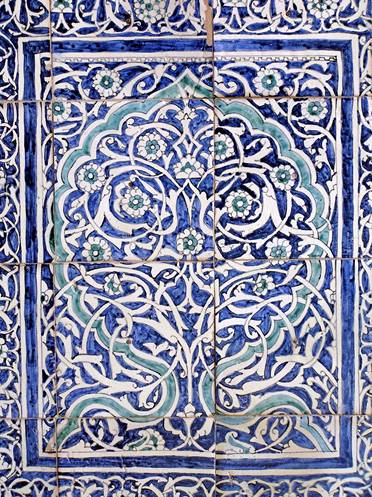

Elegant tilework in Bukhara

The town used to be full of ponds or reservoirs. Most of these were filled in long ago for health reasons (Bukhara was infamous in the past for its appalling sanitation and visitors wrote with horror of guinea-worm and skin diseases contracted from the open sewers). But one large and attractive pool remains in the centre of the old town, the Lyab-i-Haus, providing a focus for the social life of the city. In 1966, one side only of the Lyab-i-Haus was lined with dusty chaikhanas where a few turbanned old men sat on low platforms and drank green tea and smoked hookahs. Now the chaikhanas completely surround the pool and have become smart café-restaurants with proper tables and brightly coloured cushions. But they are not just for the tourists; early in the morning the old men can still be seen, and at night the café-restaurants are thronged with locals consuming huge kebabs. One of the days we were there was “National Children’s Day”, and most tables were occupied by Uzbek families with large numbers of children, the girls all in fantastical frilly dresses.

The Lyab-i-Haus in Bukhara in the morning, before the crowds arrive

The Lyab-i-Haus restaurants were not cheap (i.e. we found ourselves spending $10 a head rather than $5), but the food was much better than hitherto on our trip – in particular there was a choice of really good salads (I don’t know how visitors manage if they refuse to eat salads on hygiene grounds, as they condemn themselves to a diet of soup, kebabs and bread). Our hotel persuaded us to go for Kathryn’s birthday dinner to what it described as its “own restaurant”. It turned out to be in a private house some way away and to which we were led by a small boy. We sat on a roof terrace, the only diners, and were given an excellent meal – interesting salad hors d’oeuvre, a very good meat and cabbage stew and ice-cream with fruit, washed down by a not very nice sweet red wine. At the end of the meal, our host came to take a photograph of us to put on his website, so maybe we were the first independent travellers that they had served.

The many mosques and madrassas had been further restored since my last visit, but the old town was much as I remembered it – a maze of dusty unpaved streets, the almost windowless walls concealing attractive courtyard houses. Our “boutique” hotel was one such, and very nice too (although the beautifully tiled bathroom turned out to have the usual plumbing oddities, including a shower which spurted fierce jets of water from its joints but gave out only a trickle from the official shower-head). Cars can only just squeeze along these streets and most do not even try, so the old city is mercifully car-free. There was probably only rudimentary plumbing in most of the houses when I was here last; now there are water pipes at head level running along the outside of the buildings, not very elegant but probably cheaper and more earthquake-proof than underground ones would be. Nevertheless, in 20 years’ time these pipes will no doubt have been buried and the streets covered in tarmac, cutting yet another link with medieval times.

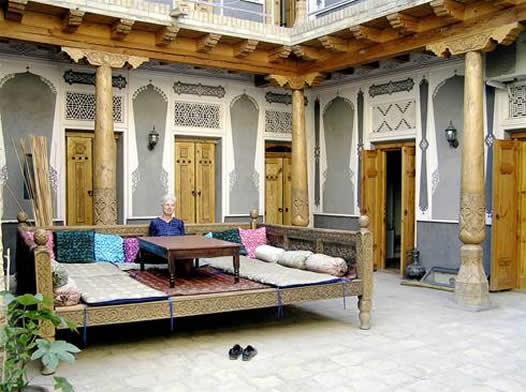

Sophia sitting on the divan in the courtyard of our boutique hotel in Bukhara.

The main difference from 41 years ago, however, is in the explosion of tourist shops. Commerce is everywhere. Several of the cross-roads in the old city have domed roofs over them, creating a shelter from the heat and glare in which mini-markets can flourish. When I was here last, these covered areas were almost empty – I think one had a few suzanis (the embroidered hangings which are the Uzbek textile speciality) hanging on a wall. Such few shops as there were in the town consisted of drab general stores with under-stocked shelves. Now, all the covered markets are overflowing with every sort of tourist tat, on the whole pretty attractive stuff: suzanis, kaftans, scarves, pottery and Turkmen-type rugs. Many of the old madrassas (religious colleges) have also given themselves over to commerce, with every one of the student rooms round the inner courtyard housing a shop or workshop selling the local handicrafts. Even the mosques usually have a retail opportunity inside the main entrance. So it is quite hard to find a monument that is not festooned with colourful hangings. Everywhere, shop-keepers pop out with what we soon realised was a standard cry of “just looking, just looking” – disconcertingly parroting back the tourist’s eternal reply when faced with the over-persistent salesperson. All the stall-holders could speak some English and French, and for the first time we felt that we were really in a major tourist destination.

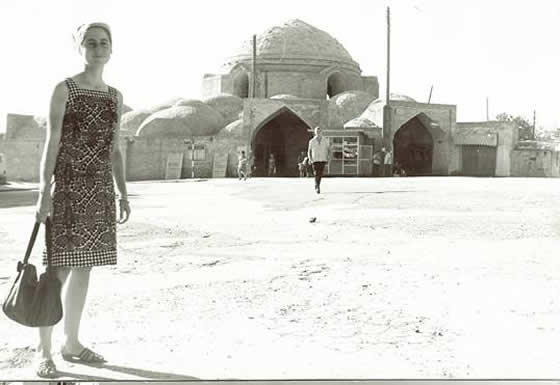

Sophia standing in front of the entrance of a shopping arcade in Bukhara in 1966

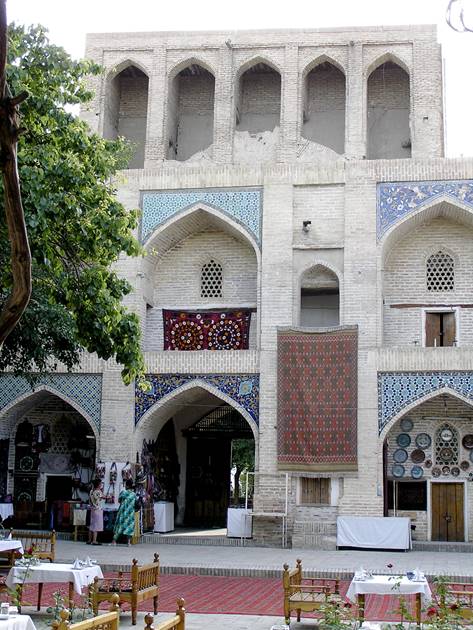

Entrance to a shopping arcade 2007

Retail opportunities in a madrassa in Bukhara. Often, every one of the erstwhile student’s cells has a tourist shop in it. In this madrassa, a restaurant had also set itself up in the courtyard.

Suzanis for sale in a former madrassa, Bukhara

Bukhara once had 127 madrassas. When I was here last, there was only one working madrassa (which was the only one in the whole of Soviet Central Asia and which I visited with my Intourist guide) and only a couple of operative mosques. Now there are apparently several working madrassas and the main one is now so fully functioning as to be closed to visitors. Many of the mosques are also now operational, although the more distinguished of the ancient ones seemed angled more towards tourism than towards religion. When we poked our noses into one that was not a distinguished ancient monument, we were immediately invited inside by the caretaker, who proudly showed us round the entire complex, including the washing area, well-tiled with lots of low taps; the loos (tiled squatters); the imam’s shower; and a cooking area. As for the mosque itself, next to the usual white-board displaying the hours of prayer there was a large thermometer; and the aspect of which the guardian seemed most proud was the fact that the temperature inside at a mere 34º centigrade was a full 10º cooler than outside – no doubt one of the chief pulling-points in summer for the less than whole-heartedly religious.

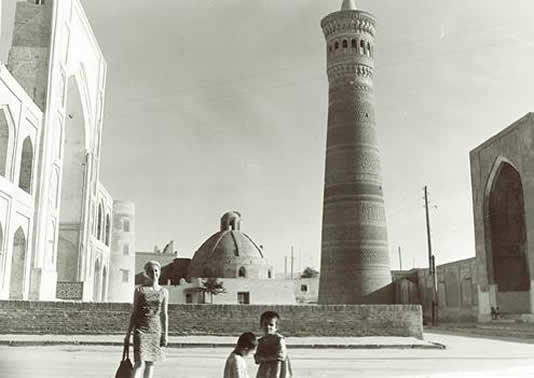

Sophia in front of the Kalon Minaret in 1966

Sophia in front of the Kalon Minaret in 2007

Emir's Summer Palace We made one trip out of town to see the early 20th century summer palace of the last Emir of Bukhara – a most marvellous piece of kitch, mixing Italian renaissance style rustication with Islamic pointed arches. Inside it was full of hideous Chinese pots; reproduction Louis VIII chairs; German tiled stoves (one with tiles of an attractive art nouveau floral design, marred by some of the tiles having been put together upside down); and peculiar pieces of furniture at whose function we could only guess.

The emir’s summer palace in Bukhara

Decoration inside the Emir’s summer palace, Bukhara

Pavilion at the Emir’s summer palace in Bukhara

Mausoleum of Khazreti Mohammed Then we went on to a mosque and mausoleum complex marking the grave of one of Sufi Islam’s main saints, the 14th century Khazreti Mohammed. It had been done up in great style, with funds from Turkey and Pakistan, jockeying for influence, and came complete with a little Islamic museum. It was a Sunday, and the complex was full of local visitors. The most popular attraction was the leafless remains of an old tree with its branches resting on the ground. According to legend, this tree sprouted from the saint’s staff. People were queueing up to crawl under one of the branches, which was apparently what was needed to benefit from the tree’s holiness. The exercise involved getting down on hands and knees, quite difficult for some of the more elderly visitors, so one hoped that the wish or indulgence thus attained was worth having. Despite the holy tree, however, our impression was that most of the many visitors were there simply because the place made a good Sunday outing.

Courtyard at the mausoleum complex of Khazreti Mahommed: a good Sunday excursion

Bukhara to Samarkand: 5-6 June 2007

Nurata

On our way to Samarkand we stopped at various Silk Road sites along the so-called Royal Road, including Nurata, where a hill-top fortress was built – or rather rebuilt – by Alexander the Great during his siege of Samarkand. Not much remains today of the fortress, although we clambered over the usual mud-brick lumps in the company of a Swiss group. Below the fortress there is a well-known holy spring, an important pilgrimage site. Indeed, the whole complex seems to be treated as a holy site, judging by the number of wish-rags that we saw tied to the many low-growing scrubby bushes on the ruins of the fortress.