JOHN (JACK McLEOD GRIGOR TAYLOR (1884-1962): John’s father

The account below is based on what John told Sophia about his father and also on a short incomplete autobiographical note that Jack left.

John (always known as Jack) McLeod Grigor Taylor was born in 1884 in Singapore, where his father was General Manager of the Eastern Telegraph Company. John remembered being told a couple of stories about Jack’s childhood. Jack came back to England with his parents at the age of 4. It was winter, and when Jack first saw the leafless trees and snow, he asked why England was full of iron trees and “fluff”. He also thought that the sheep he saw were a type of camel. On a later occasion, when Jack and George were on a train with their mother, and were arguing with each other, Jack replied to his brother “bollocks”. “What did you say Jackie?” asked his mother in ominous tones. “Oh, I was just telling George about some bullocks over there”.

Jack was educated at a preparatory school in Blackheath and then followed his elder brother to Cheltenham, a public school that was well known for its success in preparing people for the Army. And in due course Jack did indeed go on to Sandhurst. He passed out of Sandhurst sufficiently well to join the Indian Army – only the top 30 or so (out of 150) could expect to gain admittance, as the Indian Army was more in demand than was the British Service. This was because the pay was better and officers were not supposed to need private means (unlike service in the British regiments). Indian Army officers also gained positions of authority earlier, and could easily be commanding companies of 150-200 men by their early twenties. A particular attraction for Jack was that sporting opportunities in India were much more readily available than in the British Army. He was a tall, well-built man who excelled at a number of sports, notably rugby and hockey (he did not have the patience for cricket). Jack was fond of telling John anecdotes of his early days in the Army, and much of what follows was based on John’s recollection of these tales.

Jack was was a man of considerable charm and “jollity” (in the words of his son). He was also a dedicated and enthusiastic professional soldier to his core. His attitude may be illustrated by a quote from a 1918 letter to his younger brother Bobs, commiserating with Bobs on the latter’s “natural disappointment” at operations ending before he had seen a shot fired in anger. He wrote: “I don’t know why that is the expression – no soldier is angry when firing off his rifle – on the contrary, he ought to be calm and collected, but is, as a rule, somewhat excited!” (Letter of 8.12.1918)

Jack in Hong Kong

The Indian Army did not serve only in India, but provided the military backbone all over the eastern part of the British Empire. One of Jack’s pre-First World War postings was to Hong Kong with his regiment as part of the garrison there. He always said that he had the time of his life there. His week-end days consisted of getting up and playing a game of tennis before breakfast; then after breakfast perhaps water-polo, or a hockey or football game with the men; or cricket with some of the British Army officers also stationed there (it was not then a game played by the Indian Army). The evenings were for an active social life, including dancing and moonlight picnics.

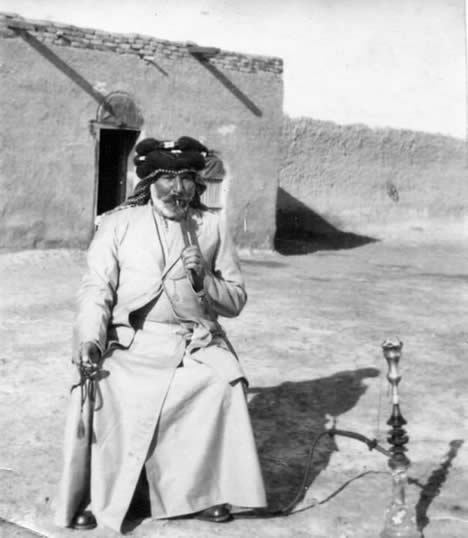

Hong Kong 1905. Jack captioned this photo “Does he not look a lazy, devil-me-care sort of officer?” It was at the time of the Russo-Japanese war (1904-5), and the Russian fleet had just been sunk by the Japanese while the Russian officers were allegedly asleep. Many Russian prisoners were taken. The Russian officers were brought back to Hong Kong and were paroled to Jack’s regiment. Generally, Jack commented, the prisoners spent most of their time drinking, but gave little trouble Jack nevertheless that to dress up each morning as for parade – medals, sword, gaiters etc – and go to their quarters and escort them to breakfast in the mess. On the first occasion when he went to fetch the Russians, for some reason the breakfast was not ready. He asked if they would like a drink while they waited, thinking of tea or coffee. But the Russians asked for Drambuies and promptly upended their glasses. “Would you like another?” Jack asked. “Yes please”, and they downed at least two rounds of Drambuies before breakfast. No wonder, Jack thought, that they had been asleep when the fleet was attacked by the Japanese. Jack became the ADC to the Governor of Hong Kong, and made such an impression that he was offered a permanent post on the Governor’s staff. But he saw himself as a regimental soldier, and he was very taken with the Indian side of his life. So he declined, but retained forever a tinge of regret about what might have been, had he accepted the offer. He returned to India in 1908, first to Bangalore as adjutant, helping with the administration of the Regiment. He learnt Persian in his spare time and indulged in his love of hunting during his leave. He wrote in a memoir:

He did, however, write much later to John about the following somewhat hair-raising episode:

Jack moved to Bombay as Station Staff Officer in 1913. When John was posted to Bombay in 1942 and spending time at the Bombay docks, Jack wrote him the following account of his time there:

Mesopotamia After the First World War started, Jack was part of an Indian Army expeditionary force to Mesopotamia (now Iraq), then part of the Turkish or Ottoman Empire. It was a hard life, what with the heat and illness. He described conditions to his mother:

(It was thought at the time, although on no evidential basis, that such spine pads protected against sunstroke in tropical climes. They would have done far better to have worn all-enveloping clothing like the Arabs.) Mesopotamia did not exercise on him any of the charms of India. In a subsequent letter he commented:

The force sailed to the Shatt al-Arab in the South of present-day Iraq and proceeded with great dash and by a series of brilliant manoeuvres to fight their way up to Basra, despite a much superior Turkish force supported by Arab irregulars. They took Basra, which became the main British base in Mesopotamia or “Messpot”, as it became known to the British.

On one occasion in a small village near Basra, he was duty officer, which meant that he had to go and inspect the guard (of Indian soldiers). In those days, that meant putting on full uniform with sword, topi and black gaiters. As he was walking towards where the men were accommodated, he was approached by a village dog which began barking at him. It was joined by others, and soon he was surrounded by a really rather terrifying pack of snaring semi-wild dogs. He had to draw his sword to defend himself until he was rescued, feeling rather sheepish, by his men who had heard the dogs and come to investigate.

After Basra, the next objective of the expeditionary force was Baghdad some 200 miles away. This time, things were a lot more difficult. The two rivers of Mesopotamia, the Tigris and the Euphrates, were fringed by 200-yard-wide palm groves, but beyond those it was absolutely howling desert, except in the wet season when the whole area was flooded. In summer the climate was scorchingly hot. The Turks had by then got reinforcements and new modern German weapons. The Indian Army contingent, on the other hand was badly equipped and had no proper supply-line or hospital back-up. Illness, often fatal, was rife. Their main hope was to sneak out into the desert by night and then to surprise the Turks. In the wet season, they had to take to canoes with steel shields on the front – the “Battle of the Regattas”. On one occasion, what seemed to be a large force appeared to be approaching across the desert in a cloud of dust towards the Indian Army positions. Refuge was taken in the trenches, but the enemy force turned out to be a herd of wild boar, at least one of which Jack shot with his pistol. Jack captioned this "Wading through the floods the same as Noah's ark dealt with" The Indian troops finally made it to the Arch of Ctesiphon on the outskirts of Baghdad, but were unable to take the city. There followed a long stalemate until the decision was taken to withdraw to Kut al-Imara. It was during the withdrawal that Jack was wounded. He picked up a rifle to shoot at a Turkish soldier who was aiming at him, but the Turk shot first and hit Jack in the side of the head. Fortunately the shot came just as Jack was bending his head to get a sight along his rifle, or the shot would have hit him full on. Even so, he was quite seriously wounded. He was knocked unconscious and at first his troops thought he was dead. But after some argy-bargy one of his Indian officers decided that he needed to get a mule-cart to take “Taylor-Sahib” down to the river. Jack recovered consciousness to find himself on the mule-cart. He was transported with many other wounded and dying down the river to Basra on an extremely ill-equipped ship with no latrines, and was then evacuated on a proper hospital ship to the UK. He had by that time been some 12 months in Mesopotamia, and had been mentioned in despatches for his role at the Arch of Ctesiphon.

There were also British Army soldiers in Mesopotamia, and there was a degree of competitiveness between the British Army officers and the Indian Army officers, whom some British Army officers were prone to accuse of going native. On one occasion this led to a particularly disturbing incident. One of the Indian soldiers had been had up for buggery. This was not uncommon among the Indian ranks and was normally dealt with by the Indian officers, with a light touch. But the British Army officer in command decided to make an example of this unfortunate Indian soldier and ordered that he should be given a large number of lashes while all the other men stood round in a “hollow square”, i.e. three sides of a square, to watch. As the flogging began, he cried out: “Why me? Everyone does it. Why not Subhedar X and Rifleman Y and Rifleman Z?” As the beating proceeded his voice gradually became fainter and there was dead silence until one by one thuds could be heard as several of the watching men fainted from the shock and emotion of hearing their names called out. Jack and his Indian Army brother officers, in no way sympathetic to homosexuality, were shocked at the way the whole affair had been staged.

Jack’s head-wound took some time to heal; indeed, he continued to be plagued by abscesses for years afterwards. When he was well enough, he was posted to coastal defence in the UK. There are few stories from this time, but he did tell John about a visit to the coastal defence forces by King George V, who he reckoned spoke with a guttural and slightly Germanic accent.

Jack finally got himself posted back to Mesopotamia in the last years of the 1914-18 War, first on regimental duties, then on secondment to the Indian Political Service. This was an elite body recruited half from the Indian Civil Service (the “heaven-born”) and half from the Indian Army, from among those like Jack who had shown themselves to be brighter than average. In particular, Jack was exceptionally good at maps (a gift he passed on to his son John); and had learnt a number of local languages – he had had to learn Hindustani on joining the Indian Army, but had also taught himself Persian and then Arabic. The Political Service had a number of roles. It supplied the British “minders” who liaised with the maharajas still in charge of independent states within British India, to seek to ensure that they did nothing against British interests. It also manned British Embassies in the countries around India, and supplied people to act as local administrators in areas like Mesopotamia which by the end of the War was under full British control, the Turks having been chased out.

In 1917, Jack was posted to a mixed desert and marsh area near Basra, where he was the senior administrator. The diaries* of Ronald Storrs, a proconsular figure travelling in Mesopotamia at the time, record a meeting with Jack. “At about 5….I walked across the bridge of boats [probably over the Tigris] to look up the local Political, Mackenzie, whom I found absent, his place taken by Taylor, shot through the head and ulcer in eye: now recovered and hoping to make a career in Mesopotamia. Took me across to Club in Political bălăm, and sent me back to S.I. [the boat on which he was travelling, probably Star of India]. The bălăm rocked and took in so much water that I turned to abuse the bow gondolier, only to find him fallen into the Tigris, from which his heels emerged foolishly, to the delight of the ladies washing on the bank”.

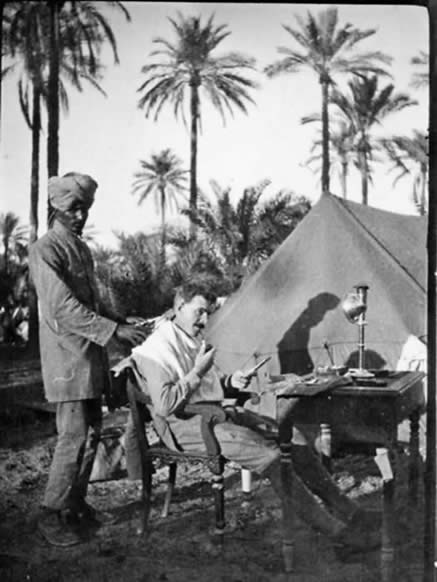

A diary sent to his mother about the first tour that he made of his area is attached at Annex A. Jack used to do business with the locals sitting at a collapsible table outside his tent. He told John a number of stories about his dealings with the local sheikhs or tribal leaders. One who came to see him complained of being constipated. When asked for how long he had not been, he replied “six weeks”. “Ah,” said Jack, “I’d better give you some Army No. 9” (the strongest laxative available for the soldiers). A week later the sheikh came back complaining of having diarrhoea – “I’ve been four times in the last week”.

On another occasion Jack tried to admonish a sheikh who had allegedly been spending too much time among the fleshpots of Basra rather than managing tribal business. “You’ve been ignoring your responsibilities and spending too much time with girls in Basra”. The sheikh looked blank. “Oh no, sir, nobody could say that of me”. “But you’ve been seen several times going into establishments in Basra”. The sheikh’s eyes suddenly lit up. “No, no, sir, that was boys”, he said triumphantly. * Orientations, Nicholson and Watson, 1945.

Having a pow-wow while on tour

Talking to a Bedouin family

"One of my sheikhs"

In camp

Jack left a written account of one particularly trying experience when he was involved in settling a dispute between two sheikhs, which is at Annex B.

Jack was keen to learn Arabic and did end up speaking it reasonably well. But he seemed to learn languages chiefly by going around speaking to the locals, and he complained that too much of his time had to be spent in offices for that. His French (an international language at the time) was also patchy. He wrote in a letter to hos mother:

Jack did not follow up thoughts of remaining a “Political”, as he soon returned to regular soldiering, as a Major, still in Mesopotamia, where the Raj Rif continued to play a garrison role after the War, trying to ensure law and order. There were a number of small groups of soldiers posted to remote areas with whom Jack kept in radio-telephone contact. Worried that he had been unable to raise one of these detached groups for some days, he sent a reconnaissance party to their post. All were found lying dead – two British officers and perhaps some two dozen Indian officers and men. The senior officer was found with his hand burnt hanging over a stove where he had, as his last act, been burning the confidential regimental papers. They had all died within a few days of the extremely virulent Spanish flu that swept the world in 1918-1919.

Back to India

Jack returned to India shortly afterwards. He commented in old age that he seemed to have been born to travel and keep moving; during his 40 years’ service, he claimed he only once stayed in one place for more than one year at a stretch. Back in India, he joined the 2nd battalion of the 6th Rajputana Rifles. The battalion had three periods of frontier campaigning: at Waziristan (19922-24); Baluchistan – Quetta and beyond (1924-26); and the Khyber Pass on the North-West Frontier. In each of these areas, there were changes to new forts or posts every six months or so.

In the first half of the 19th century, Sind and the Punjab had been incorporated into British India. They were irrigated farming areas that depended on peace and good administration to prosper. But they were on the border of a mountainous region of what is now Afghanistan, inhabited by lawless tribes whose favourite sport was raiding the fat lands below, stealing cattle and taking whatever else they could. British policy was to use a mixture of force and bribery to keep the unruly Afghan tribesmen of this no man’s land frontier region out of British-controlled India. They used both the regular Indian Army forces on the frontier of which Jack was a part and “irregulars”, forces made up of amenable (because well-paid) mountain people led by British officers drawn from the Political Service. The latter would wear Afghan kit and speak the local language, and were the inspiration for the heroes of John Buchan. For both the regular army and the irregulars, this was dangerous work, for the Afghans were expert snipers. The terrain was exceedingly difficult, with no vegetation and no cover, and the extremes of temperature were enormous. There was a steady stream of casualties, killed and wounded. The tribesmen would plant bombs in gardens, or by the jumps at gymkhanas, blowing the horses to pieces. No British officer ever did anything more than twice in the same way, as the third time he would be ambushed and killed.

Tribals on the North-West frontier, possibly including a British agent.

Fortified signal post on the North-West Frontier, 1920s.

Jack spent the rest of his military career in India, being promoted to Lt-Colonel in 1931, the normal top post to which Indian Army officers aspired. From 1926 to 1929, he was deputy commandant of the Rajputana Rifles “cantonment” at Nasirabad in Rajasthan. His final post (1932-34) was in Ahmedabad in Gujerat, the centre of the Indian textile industry, with one million inhabitants and 95 cotton mills. In a note that he left, he commented that in 1832 it was booming, while Lancashire cotton slumped, “and so it will always be if we try to compete with cheap labour. Let our fellows concentrate on the more scientific industries and manufactures. We can have free trade in the world if it is organised and currency is properly controlled.”

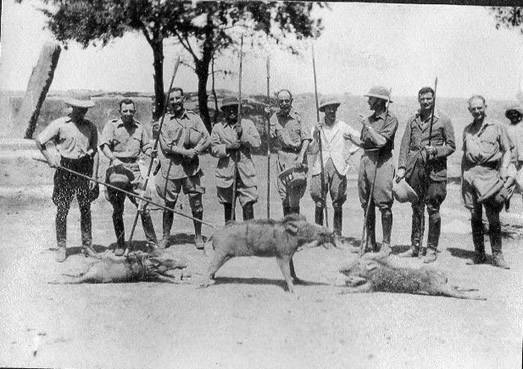

Jack continued to hunt various sorts of game, shooting snipe and other birds for the post and also going crocodile hunting and pig sticking. The latter sport, spearing wild from horseback, originated in Bengal and was taken up with enthusiasm by many British officers (and maharajas). According to the 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, it was encouraged by the military authorities as good training because "a startled or angry wild boar is ... a desperate fighter [and therefore] the pig-sticker must possess a good eye, a steady hand, a firm seat, a cool head and a courageous heart."

Crocodile-shooting: Jack centre, Dora left.

Pig-sticking

Marriage

Just before the First World War, Jack had married Nellie Angelo, a descendant of an Italian master of swordsmanship who had come to India in the 18th century to teach sword-play to the maharajahs. She ran off with a brother officer while Jack was away at the War, and in 1921 Jack married Dora Ducé, a schoolteacher from England who had come out to visit her sister in India. They married at St Mary’s Church in Poona (now Pune). John, during a visit to India in the 1980s, visited the church in Poona where the wedding took place and found the relevant entry in the church register. About a year later John was born in Ahmednagar, where there was an Army maternity hospital. He was their only child. It seems to have been a good marriage and they both enjoyed India. Fortunately, they were lucky enough not to suffer the ill-health that so plagued the British in India.

Dora as a young woman

St Mary's Church, Pune Retirement

Jack retired in 1935 and he and Dora returned to England, settling first in Pinner. They took John on a long family holiday round England and Scotland. Jack was extremely attached to his Scottish origins and had always talked them up to John, and this early indoctrination made the Scottish trip something particularly memorable for John.

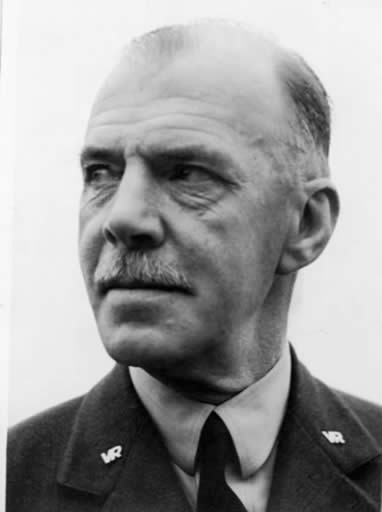

For a year or two, Jack worked for the “Royal Empire Society” (which subsequently became the Commonwealth Society), a body which aimed to propagate the ideals of the Empire. Jack was a “travelling secretary”, and went to both India and Africa speaking on behalf of the Society and drumming up new members. He then trained as a golf club secretary – this was one of the jobs that ex-Army officers were thought to be good at. But before he could take up a real job as a secretary of a golf club, the 1938 Munich crisis took place, and Britain began seriously to re-arm. Retired officers were invited to volunteer to take non-combatant jobs, and Jack volunteered for the RAF, which was expanding at speed. He was given the junior rank of Flight Lieutenant. But as he looked every inch the Indian Army colonel – tall, broad, mustachio’d and commanding – those who were technically his seniors in the RAF treated him with great respect. On one occasion, when he went to an RAF base to check what supplies they needed, the Group Captain in charge called him “sir”. Jack replied firmly “I am not sir, sir, you are sir, sir”.

Jack in retirement After the Second War, Jack and Dora finally retired to Fuchsia Cottage on the Isle of Wight. Dora died of heart disease in 1959. A year or two later Jack, who was still an extremely vigorous man, married again, to the 20-years-younger widow of a Colonel. But within two years of the marriage he died of lung cancer (he was a heavy smoker) at the age of 78.

Fuchsia Cottage, Isle of Wight

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ANNEX A DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A POLITICAL OFFICER IN AMARA, MESOPOTAMIA, 1917 Captain (later Lt. Colonel) John McLeod Grigor Taylor (1884-1962) of the Rajputana Rifles, Indian Army, served in Mesopotamia during the First World War. He was seconded to the Political Service from May 1917 until September 1918 and was based in Amara. This is a diary-letter that he sent his mother of the first tour he made of his district between 25 and 29 September 1917. Tuesday 25 September Left at 6.45 a.m. in launch to starting point a mile away, where I met my cavalcade of 6 men. Kit went by mashoof (Arab canoe). Started off at a gentle canter, Arab saddle very uncomfortable as usual, especially for my excessive proportions in the nether regions, and I soon began to wear a bit on the outshirts! However, by constant manoeuvring and shifting of position I distributed the rubbing through this and the following days and returned with a whole skin somewhat hardened. About half-way to destination 15 mounted men with a Sheikh’s son met me, and after exchange of questions and a few false compliments we did a good stretch for 3 miles, their object being to show off their blood Arab ponies. But they had not counted on my steed, exchanged with one of my party after we’d gone a few miles in first half, and I out-distanced them all, one of my previous escort being felled. Inspected a police smuggling post for goods from Persian frontier and shortly afterwards we reached the Sheikh’s dwelling, by 9.a.m., having done the distance of 25 miles in the record time of 2¾ hours. As is the custom, I was ushered into the “mudifa” or guest house (a large open hut made entirely of reeds) of the Sheikh and seated with a certain amount of ceremony on a sofa with many cushions. After the usual serving of coffee and hot tea with no milk, other Sheikhs began to call in and have a talk, and this went on steadily till 2 p.m., when we had our fist meal of the day; I’d only had a cup of tea and biscuits before leaving, but did not feel particularly hungry. Except for half a tin of biscuits, some Horlicks milk tablets and my pocket medicine chest, I had brought no food or drink with me and from now on till my return partook of only Arab meals in Arab fashion. They have two meals a day at about noon (the dinner) and about 7 p.m., both consisting of more or less the same food, namely 2 or 3 large bowls of well-cooked rice in the centre of the carpet surrounded by soup-plates containing roast chicken, excellently cooked and well-flavoured mutton, country vegetables and onions, “lebben” (sour milk curdled), and a “shape” of pudding, rather sweet and tasteless. Occasionally at the dinners plates of a dozen or more hard-boiled eggs with the shells skinned are laid out (I ate 6 at one meal in addition to several handfuls of chicken and rice!!). No liquid is served or drunk during the meal, and the whole meal is a serious business with little talking and is soon over. No forks, knives or spoons are used, and before sitting down on the ground to it a bowl of water is passed round for each person to wash their right hand in, this hand serving as the spoon. Quite an amazing show, and by Jove, some of them are gluttons; they shove down enormous mouthfuls with hardly a pause for 10 minutes, and then abruptly get up and move away to wash, smoke, and drink more coffee or have a glass or two of sherbet. This latter may be of several kinds, some tasting like lime-juice and water; others made from dried sweet limes were most palatable. No women are present. Altho’ allowed absolute freedom in moving about in the country and villages, they are kept apart from the menfolk at their meals and conversations. Inspected the little municipality 2 miles away in the afternoon, principally to look out for any smuggling and to ascertain the amount of rice stored in the Govt, store-house. To bed at 9.30 p.m. on a large wooden bed with soft mattress and colossal mosquito net to keep out the sand-flies and had a great sleep of 7 ½ hours (quite long for me) till daylight at 5 a.m. [Wednesday 26 September] Sun rises 6 a.m. now and max. temperature (shade) while I was out ranged between 98° and 102° - with soft breeze moving about all day, I did not notice the heat at all. “Chota hazri” [Hindi for breakfast] consisted of cup of hot milk and piece of Arab bread (“chupatti”). Did 2 hours in mashoof down pretty canal to meeting place with 7 other Sheikhs, my object being to ride round their whole district and estimate amount of rice in cultivation, proportion of each variety (there are 3) and general barrenness of the land, for this has been an exceptionally dry year as regards floods. The country was a network of small canals, most of them navigable by small canoes. After riding half an hour, and while crossing a canal, my pony stuck in the mud, reared, and came over with me into the water, leaving me wet through and covered with slimy mud. The Sheikhs were much concerned for my feelings, but when I arose from the canal with a beaming face, they relaxed and we all had a good laugh over it. Had myself photoed on the spot. Had to replace my coat by an Arab cloak. They led me a nice dance this first morning. Feigning to misunderstand my plans and orders for the day, they led me away from the tracts where the best rice was sown, their purpose being to only show the barren parts and accentuate their demand for reduction of revenue. After 2 hours’ wasted ride (the first game having gone to them), I did the leading and took them where I willed – also making them dismount and walk inti the mud and swamps with me. For this I was dressed in full khaki rig with heavy boots, but they in Arab fashion, Sheikhs and all, displayed the nakedness of their bodies by lifting their skirts well above their middles. And an uncanny sight it was too! They have no shame about this sort of exposure, contrary to the habit of Indians. While wandering round, I questioned many groups of cultivators, men and women, and besides extracting information which I could not out of the landlords and farmers. I gained much instruction by making them describe in detail the various tasks of reaping, threshing, packing and grinding the rice. This all added to my small Arabic vocabulary and I’ve returned with more confidence. That was the second game, which I won. Dinner (or lunch) was served at 1 p.m. and then they desired me to sleep and said there was nothing more to see. However, I knew my ground by then and had gained the initiative, so I led them a dance of several miles’ walk in the hot afternoon (a Sheikh does little walking!) into some other nice swamps that I’d spotted. There I found what I was searching for – miles of the best kind of rice, and with that won the rubber. On the way back, most of the conversation consisted in their attempts to induce me to reduce the revenue, but I gave them no verbal decision, only telling them that I had come out expecting to be helped, that they had lied consistently throughout the morning until found out, and that if they did not help the Govt. they could not expect to be helped. After dinner I returned back 4 miles by canoe in the moonlight to sleep at a convenient spot handy for my long ride the following morning. On the way, some Bedouin nomad Arab encampment was celebrating a marriage by singing and dancing, and I stepped ashore for 10 minutes to watch the strange proceedings. Caused much consternation by being able to mimic the Arab woman’s wail.

Thursday 27 September Up at 5 a.m. and 3½ hours’ ride to a small fort in the middle of the Desert where I met the representatives of another sheikh and settled a boundary dispute on the spot after an hour’s parlay. First half hour both sides spoke at once while I lay still among cushions and sipped coffee and sherbet, my young interpreter occasionally joining in their wrangle. Next quarter hour each side spoke in turn and quieted down. Last quarter hour, with occasional interruptions, I repeated demands of both sides, told one side (of the district I had been through) that they were all liars and I had heard 7 different accounts from them, and then gave the decision in favour of the Sheikh [who was] to accompany me for the next 2 days. Sounds as if my decision was self-protective, but it was true Justice. After short ride in new district we boarded canoes and sailed into the swamps, through lake after lake of 3 to 4 ft depth and surrounded by tall reeds, for another 3 hours until we came to the point where a canal spread itself into the swamps we had passed through. Then another hour up the canal before we lunched with a farmer at 2 p.m. (first meal of the day). I must have seen at least 30 dead sharks along the banks and many live ones which we only caught sight of for a few seconds. Some were quite 6 ft long. The Arabs kill them with harpoons but don’t eat them. Miles of rice on either bank. Reached first destination of minor Sheikh at 5 p.m. where we dined at 7 p.m., moving on again for another 2 hours to the capital of the big Sheikh, where we were received with pomp. Slept like a top.

Friday 28 September This was the day of the big Mohammedan festivals when no work is done. In this place I had a room to wash and dress in. On turning out at 6 a.m. I found the principal Sheikh seated with all his counsellors receiving congratulations from all and sundry who kissed his hand. As I entered the large open guest hut, they all arose and we exchanged the usual “Salam-allah-bil-khair” (Good Morning) and “Salam aleikum” (peace be upon you). Then I shaking the Sheikh’s hand warmly shouted the congratulations of the festival, viz. “Id-elmabarak” and “B-Ayouk Sāid” (May your days be happy); and to others of lower rank added “Babathauk arus” [may your fortune bring you a bride] (which is a little vulgar but quite the thing today). After a quarter hour’s coffee, we walked a little way into the desert to watch the assembly of all the Sheikh’s armed retainers (his fighting force), some 3,000-odd, in several lines, and at a given signal they all, footmen and mounted, charged down on us, waving rifles, shouting and waving the red, yellow and green war banners carried for every 50 to 80 men, stopping short a few yards away. Then, forming circles, they danced round singing for an hour or more, shots being fired occasionally into the air. I took a couple of photos, but don’t know results yet. They looked most wild and some of their songs were about the Government, one demanding the removal of a barrage just been built which reduces the amount of irrigation water for their district. From this we witnessed the sheep being killed for the feast, and then I spent a rather boring morning wandering round paying formal visits, including a few minutes’ glimpse at the Sheikh’s female household all dressed up in their best gowns with gold trinkets of various kinds hanging from their noses, ears, necks and ankles and fastened across their chests. What struck me more than anything during the whole of my visit was the particularly lazy life the majority of them lead. The peasants toil away at their daily tasks but the Sheikhs, their immediate assistants and their armed retainers (who are all fed, housed and maintained by the Sheikhs) do absolutely nothing from day to day. Many times I questioned groups of them sitting around as to whether they did anything besides sitting, eating and drinking coffee and they frankly admitted without any shame that such was the case. All those “hoshiya” or retainers exist for is a possible fight with some neighbouring tribe which only used to occur every two or three years and then only lasted a month or so. Each man keeps his own rifle and ammunition, but there is no musketry, training, inspections, pay, even register of numbers, rifles or ammunition, and they never even clean their rifles. I got several of them to talk of their tribal fights before the war, and of their dealings with the Turks in the old days. Spent a rested afternoon writing up notes of various businesses I had discussed, and took a quiet stroll along the rivers in the evening. Three canals joined close by one house. One can hardly call them canals, for altho’ shallow, they were all between 80 and 200 yards broad. In evening had a long interview with two dismissed Sheikhs who now live on charity but in first year of war fought stubbornly against us in the Abwaz region. Gave them no change. They wished to be re-installed. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ANNEX B

MESOPOTAMIA 1918. A day with bribery, fleas and heatstroke.

It was in early July 1918, with the thermometer registering 120 in the shade, that as a Political Officer in charge of a District I passed through a most singular experience. The matter in hand was to settle a boundary dispute between adjoining Sheikhs, one powerful and rich, the other insignificant and poor.

I represented the British Power as Umpire over an Arbitration Committee consisting of three Sheikhs. After a 60-mile journey by launch and canal, two days were vainly spent in endeavouring to examine the surrounding desert, for at this time most of the land was covered by the annual inundations. Maps of past approximate boundaries were useless; we were confronted with mile upon mile of floodwater which in some places was 7 feet deep. The redistribution of the rich silt, so invaluable for the crops, had given rise to the dispute – the entire face of the country was altered. Each side claimed and counter-claimed, and produced ancient history or fantastic stories to prove their respective rights. So the long hot hours wore on, while the writer gave no decision, but listened attentively.

After two days of fruitless discussion, we reached a small village consisting of seven reed huts on a mud mound. We had done all we could in the way of reconnaissance and decided to rest for the night. My bedding roll was placed in an empty hut. The usual excellent Arab dinner of well-cooked meat and rice being over, I interviewed each witness alone and took notes under the solitary light of a miserable lantern, while the stuffy night hours dragged on. The old demands were reiterated and I decided to harangue the assembled company with my own summary of the situation. Neither side would concede anything, and so they were dismissed.

At last the Arbitration Committee showed signs of life. Each one asked for a short private interview. No. 1, a fine upstanding bluff old Arab, came to the point straight away: “If you will only decide in favour of the rich Sheikh, there is £1500 in golden Turkish Sovereigns waiting for you,” he said excitedly.

Not a word about the justice of the case; except that when I expostulated at his want of honesty and fairness, he frankly added “personally, I think the land should be given to the poor Sheikh, but he can only offer £500.”

No. 2 was equally direct in saying “I know what No. 1 has told you, but I’ve known the poor Sheikh all my life and he has suffered many hardships to the advantage or the rich neighbour. The land is his, but he cannot offer more than £ 500.”

Quick dismissal.

No. 3, having probably known what the others intended to put forward, and having certainly heard my angry shouts, was quite demure and merely said that both sides were prepared to take my decision.

This, however, was never given. The matter was left over till the fall of the floods and I do not know to this day what decision was given.

Angry, perspiring in the damp heat, dirty (for I had had no bath or change of clothes for two days), and extremely fatigued, I retired to my equally filthy and damp couch at 1 a.m. An Arab watchman stood over the open doorway of my diminutive reed hut. At 1.15 a.m. I awoke with a string of curses at the world in general and the watchman in particular.

"What does this mean? Tired though I am, I cannot sleep; some pest is biting me all over. Bring the lamp.”

I stripped. Imagine my feelings – my body was entirely covered by masses and masses of fleas. Quite unmoved, the watchman suggested bringing a pail of water. Meanwhile, smacking and rubbing my skin violently with every known evolution of Muller’s exercises, I slaughtered the plague in thousands to no avail. As I attacked one portion of the enemy, they would gather in greater quantities on a flank or in the rear, and my efforts to defeat them piecemeal were useless. Pail after pail of water was swished over my body, and many hundreds of this vile insect must have been drowned. But their reinforcements were unceasing. We tried all kinds of tactics, both of us slapping at the same time. Frequently, pauses had to be made to recuperate from our exhaustion, and during these we would sit quietly on the ground, perspiring and panting, whilst I eked out the minutes with feeble attempts at philosophy and silent prayers for the dawn and hot sun, which I knew would disperse the enemy.

Little did I realise that the latter [i.e. the sun] would be nearly the undoing of me.

At these times, the enemy appeared to be simultaneously exhausted, for they could only be counted in hundreds. Perhaps it was only my violence that stirred them to anger and redoubled efforts, for when we resumed the offensive they seemed to come on in hordes. Occasionally, I strolled to the edge of the floods a few feet away and sat, buffalo-wise, immersed in the warm water. This would bring temporary relief. I must have drunk gallons of it to assuage my terrific thirst. I was surprised that none of the Sheikhs had heard my muttered curses and come to my assistance. I did not know till next morning that they had all suffered from the same cause and were fully occupied in fighting their own battles.

It is hardly necessary to mention that sleep was impossible – to lie still for long was fatal.

I endeavoured to disobey that excellent maxim of War: “Touch once gained with the enemy must never be lost”. But there was no line of retreat from the formidable array, and my only hope was the first streaks of light of the oncoming day – a more dangerous enemy as it turned out to be.

At 5 a.m. it came and my mind was made up. I had intended to regain my launch and return by a circuitous route. Bit I knew of a quicker way. There was much work waiting and I was anxious to reach civilisation.

Donning my damp clothes quickly, I sallied forth to rasp out my wishes, prefaced by a curt description of the terrible night. Before I could get out a word, the bluff old Sheikh came running up and shouted in Arabic “Let us get away at once, Sahib – this place is real Hell – I have been consumed by fleas as big as that”, pointing to his clenched fist. This offered me some satisfaction in that I had not suffered alone and I said “Thank God for that”.

After a hasty Chota Hazri [breakfast], accompanied by one Arab, I set off at 6 a.m. in a canoe to meet the ponies at a small Bedouin encampment, whence to ride direct 26 miles across barren desert to Amara. All the Sheikhs implored me not to do it, mainly because of my extreme fatigue and the time of year. They were feeling it too. But I was young, and desperate after the past trials.

The canoe trip took longer than I expected, and it was 10 a.m. before we commenced the almost fatal ride. Two minor disappointments attended here. My Arab companion’s steed was in foal and the Arab pony procured for me looked none too sturdy for my 13 stone. However, I had committed myself and must needs carry on.

Resuscitated with a large bowl of lebben (soured milk), carrying nothing in the way of provisions or liquid, and with no chance of meeting any human being or seeing even a tree or habitation, we started off at an easy canter across the blazing desert. Our only companion in Nature was a steady mirage.

By noon, when I estimated we had covered about half the distance, the Arab, who had been grumpy and silent, suddenly suggested that we were attempting the impossible and that his mare would go no further. He then reined in and dismounted. I followed suit. Neither of us wanted to talk; we were already feeling that the dryness of our tongues made conversation an effort. I did not reply for a while; I was thinking hard. We were both big men and unarmed. He looked fierce and was certainly much fitter than I. So suiting the action to the word, I prepared to mount, saying weakly “come on, forward”. He refused to budge. More action required, I thought. I shook him and he rose to the occasion and mounted. We plodded on at a walk, amidst the most unholy silence, each occasionally glancing at the other with unmitigated hatred, with our mouths sagging open and our tongues hanging dry.

When we had covered roughly 20 miles, I began to feel that if I didn’t drop from my saddle soon, the pony would crumble up. Whichever happened first meant the finish of the journey. And, looking at the Arab’s mare, I imagined it was going to foal at any minute. Thoughts of cool drinks began to assail me, and I knew then that the symptoms of heatstroke were fast over coming me.

At last, through the mirage, something began to quiver. What was it? Both knew the other had seen it and we strained our eyes. It appeared to be about two miles away. To my surprise, he muttered that it was no good – we could not reach it. We were then crawling along. All right, I thought, the final effort has come if we want to win through. Beating and kicking my pony furiously, I got him into a canter. His followed suit and we drew nearer to our goal. The outlying redoubts of the Amara perimeter came distinctly into view, but all was not won yet. Flopping about on the saddle, I was suddenly thrown and my pony turned tail into the “blue”, followed by the Arab. I could just see the outline of a British sentry and, felling too weak to move, I raised my hand and waved my Arab cloak, thinking he must have seen me fall. Not a stir.

Minutes went by and no one moved from the redoubt. It was now about 3.30 p.m with the sun at its fiercest. I never saw either the Arab or the ponies again, but heard that they got in all right.

I must have lain there on the burning sand for about half an hour before I regained sufficient strength to walk slowly to the redoubt, a dirty, unkempt spectacle in half-Arab dress. Although the sergeant and “Tommies” plied me with questions, I could not speak, but simply drank and drank mug after mug of lime juice and cold water. Arm-in-arm with two men, I went from post to post along the perimeter, drinking a few more quarts each time and eventually reaching my house by 7 p.m., having just staved off heatstroke. I could not eat anything till the evening of the next day.

Thus ended a most interesting experience to look back upon! One lives and learns.

J.M.G. Taylor, Major 10/16th Rajputana Rifles

|