3. FAMILY PROPERTIES IN THE 1500s AND 1600s AND THE LAMBERT CONNECTION

The 1500s saw the acquisition by the family of two important properties, Bradleigh and Lambert; and the later 1600s saw the loss of the farm at Gorwyn. From then on, Bradleigh and Lambert were the family’s two main bases.

- The loss of Gorven

- Bradleigh

- The Lambert connection

- The family’s first use of the name Lambert

- Gorvens and Gorwyns

One of the first glimpses that we have of the Gorwyns as real people at home on their ancestral farm is in a 1635 document in the National Archives1 that formed part of legal proceedings that were brought by one Francis Gorven against his father John Gorven of Gorven (as the name of family and farm was then spelt) and his older brother, John Gorven the younger. Only the statement by the old father survives, so the story is not entirely easy to piece together. But it does reveal a sorry tale of debt and family disunity.

It appears from this document that John Gorven the elder had been living at Gorven for many years and was now an elderly man in his eighties. His son had also been living in the house with him, crammed with his wife and two babies into the “kitchen chamber”, probably the room over the kitchen in the new wing built not long before. Francis had a few cattle and sheep that he pastured on his father’s land.

John Gorven the elder, who had “a great charge of children”, ran into debt to such an extent that when his daughter married one Edmund Cobley (maybe an ancestor of Tom Cobley of Widecombe Fair fame), he had to mortgage Gorven to Edmund to pay his daughter’s £40 marriage settlement. John Gorven had various other debts, which led him at one point to be arrested and imprisoned (it is not clear for how long). He was therefore unable to redeem the mortgage and Cobley took possession of the property. However, no doubt for his wife’s sake, Cobley allowed John and his wife Mary to continue living in the house. At some date thereafter, John Gorven the elder seems to have been pressured into giving his younger son Francis a lease of the property, to begin after his own death and that of his wife. In exchange, Francis promised to pay £60, part of which would go to Cobley to pay off the mortgage.

There then seems to have been a major quarrel between father and son, as a result of which John turned Francis and his family out of the house because of Francis’s “disobedient and contemptuous carriage”, although not before Francis had thrown one of the deeds of the property (then very important to establish ownership) on the fire in a fit of rage.

The legal proceedings were initiated by Francis after this quarrel, apparently to establish his claim to an interest in the property. Francis seems to have argued that his father had granted him the lease not just because of the promised payment of £60 but also because he, Francis, had done so much work on the estate. His father refuted this. He pointed out that Francis had indeed from his youth upwards lived with his father and employed himself, sometimes of his own will, about the estate. But he had had from his father “his whole maintenance, education and livelihood”, which his father believed was worth far more than anything that his labour could earn. Moreover, Francis had not repaid Cobley, despite his promise to do so.

John also argued that Francis and a friend of his had in any case put undue pressure on him to grant the lease, when he was “very old and full of infirmities”. Gorven was entailed on the elder son John, so the lease effectively cheated the latter of what was by far the most valuable part of his inheritance; and John senior would therefore support his elder son in any endeavour to get the lease declared void. If Francis was now claiming to be homeless and destitute, he had brought it upon himself by his own actions. Moreover, Francis had been heard to say that if the mortgage were assigned to him, he would turn his parents out and they could sleep under a hedge.

It is not clear how the case turned out. According to another court case in 16502, Gorven was by then in the hands of “John Gorven, yeoman”, presumably John Gorven junior who had by then inherited the estate from his father. So it seems that Francis did not get his lease (probably he failed to pay up, or perhaps he was bought out).

But it seems that the family still had money problems and by 1650 had decided that they could not afford to stay in the property. The 1650 case concerns a dispute between the junior John Gorven and a Thomas Croate of Chagford. Ten years before, John had apparently let half the property to Croate on a 99-year lease, the lease to begin after the decease of Mary Gorven, widow (presumably his mother, then still living in the property), at an annual rent of 13s.4d. Thomas Croate had undertaken to pay £90 upfront for the leasehold, the money to be used inter alia to settle various debts of John Gorven’s. So it seems that John had been forced to sell future part-leaseholds of Gorwyn to others in order to meet his financial commitments (it was not uncommon for portions of leaseholds to be sold to different people, the leaseholders sharing the revenues from the property in proportion to their holding). As soon as Mary Gorven died, the property was no doubt sublet by the leaseholders for income. This is confirmed by the fact that the parish records for the later 17th century refer to the people paying the church rate for Gorwyn as “occupants” rather than by name.

John Gorven’s debts appear ultimately to have forced him or his heirs to sell the freehold of the property to the Fulfords, the biggest local landowners, as there is a reference in a Fulford document of the late 1700s indicating that they themselves had sold the freehold of Gorwyn to the Davy Foulkes family of Medland Manor, the other big landowners in Cheriton Bishop. Gorwyn thus became no more than a tenanted farm and remained so throughout the 1700s and 1800s, passing through the hands of a succession of big landowners. There were, however, two more brief Lambert Gorwyn connections with the farm in the 19th century. In the early part of the century it was briefly owned by a rich Lambert. Gorwyn; and later another less rich Lambert Gorwyn occupied it for some years as a tenant farmer. See Chapter 13 for further details.

Bradleigh

By the 1600s, another branch of the family (probably the descendants of an earlier younger son not in line to inherit Gorwyn) were steadily building up their landholdings. Their first big acquisition – through marriage – seems to have been Bradleigh (also spelt Bradlegh or Bradley and meaning “broad meadow”), a big farm in the rural part of the parish of Crediton, near the border with Cheriton Bishop and about two or three miles north of Gorwyn. The farm still exists although it is no longer lived in. It has a large cob farmhouse (unfortunately now in a ruinous state, the original thatch replaced by a temporary corrugated iron roof to protect what remains of the house from the elements), It is at the end of a long drive and stands on a high ridge with wonderful views. Once it must have been a very desirable property.

The association with Bradleigh appears to have begun in the early or mid-1500s, when Peter Gorven (probably the Peter who was the second highest taxpayer in Cheriton Bishop in 1544) married Alice Bradlegh of the family which then owned Bradleigh (and had probably done so since at least the 1300s, taking their surname from their property). There are documents in the National Archives3 dating from the mid-1500s that record a legal dispute between Peter and Alice and her Bradlegh cousins. These documents say that Alice’s grandfather, Thomas Bradlegh, had been “seised in his demesne of two tenements, 200 acres of land, 60 acres of pasture, 20 acres of meadow and 300 acres of furze and heath with appurtenances called Bradlegh in the parish of Credyton”. It was a very large farm for the area, although the land is extremely steep – one of the current owners says it is like farming on a roof. Alice was Thomas’s grand-daughter, and through her Bradleigh seems to have passed into the Gorwyn family. She and her husband Peter were in possession at the time of the mid-1500s court case.

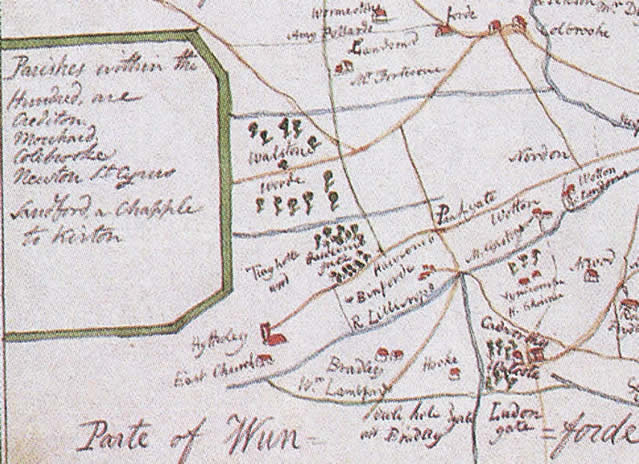

The Devon Record Office collection includes a map of the Parish of Crediton dating from 1598. It is one of those wonderful illustrated maps on which the individual farms are represented by tiny houses. Against each farm is marked its name and the name of its owner. Bradleigh is shown on the map with two houses (probably indicating that it was a sizeable establishment with cottages). Its owner is given as “Wm. Lambford”. By this time the Gorwyns had acquired the nearby farm of Lambert (on which see below). So this is almost certainly a descendant of the Peter Gorven who married Alice Bradlegh. A later court case4 reveals that in 1635 Bradleigh was in the possession of William Gorwyn, possibly a son of William Lambford who had reverted to the old name. Bradleigh remained in Gorwyn hands until the late 1800s.

Bradleigh is at bottom centre

The Lambert connection

The first reference to a Gorwyn connection with the farm now called Lambert comes in a manorial document of 15675, which records (in Latin) that in that year John Gorven held a lease for his life of half of “one tenement with appurtenances called Lampford” from Sir John Fulford, Lord of the Manor of Lampford. The document further records that John Gorven paid £10 to enable the lease to pass to his sons William and John for the term of the life of the longest living of them, according to the customs of the Manor. Then, in 1590, the 33rd year of Queen Elizabeth’s reign and a couple of years after the Armada, there is a record6 that one William Gorwyne purchased from Thomas and Huntington Beaumont “the Mannor of Lampforde and several messuages and lands with appurtenances in Crockernwell and Cheriton”. A year later, William also purchased from Thomas and Ursula Fulford a half share in “messuages, lands etc called Lampford in Cheriton Bishop”.

This is all a bit mysterious. In the Domesday Book there are two Manors called Lanford, probably two parts of a previously single domain that was split in Saxon times. The larger part became the Manor of Lampford that passed in medieval times to the Fulford family where it remained until the 20th century. It seems likely that the farm now called Lambert was in the other manor that became known as Parva Lampford or Little Lampford. In 1241, Little Lampford belonged to the Prior of the Monastery at Plympton, although later he is recorded as owning only one-third. The boundaries of manors often changed as neighbouring owners sold bits of land to each other; and manors could also be divided between several owners. The Beaumonts (a large and ancient Devon family who died out in the 17th century) are recorded as owning land in Lampford in 1504, so they may have acquired part of the Prior of Plympton’s holding in Little Lampford. Although the Beaumonts claim to have sold the Manor to William Gorwyne in 1590, there is also a record of the Wise family of Sydenham (other very large landowners) selling the “manor of Lampford” (again apparently Little Lampford) to Nathaniel Risdon of Spreyton (yet another big landowner) in 16578, so they presumably also owned part of it. The Fulfords may also have acquired land in Little Lamford to round out their estate. At any rate, it seems that William Gorwyne, to get a self-contained estate, needed to first to lease land from and then to buy out both Beaumonts and Fulfords.

The William Gorwyne who purchased the freehold of the property in 1590 must have been the son or possibly the grandson of the John who was renting it in 1567, and the family the may already have had it for some time before that. One can only guess at how they were related to the earlier Gorwyns, but certain deductions can be made from records of property ownership. In 1635, an “inquisition post-mortem” was made into the estate of a recently deceased man called William Gorwyn7, and that ascertained that he owned both Lambert and Bradleigh at the time of his death. He was presumably a son or grandson of the William Gorwyne who purchased Lambert, and his ownership of Bradleigh indicates that he was also descended from the mid-16th century Peter Gorwyn of Bradleigh mentioned above. Since the 1635 court case described above makes clear that Gorwyn had at that time long been in the hands of John Gorven, it is clear that by the early 1600s there were two quite separate branches of Gorwyns/Gorvens, one at Gorwyn and one at Lambert/Bradleigh (and judging by the number of Gorwyns in the contemporaneous Cheriton Bishop church records, there may well have been others on other farms).

The fact that the 1590 deed registering the purchase of Lampford from the Beaumonts refers to “several messuages and lands” indicates that William Gorwyne acquired more than a simple farm. Probably he also acquired various cottages and smallholdings that went with the main house. But the house that is now Lambert Farmhouse would have been the main dwelling, and he probably lived there. The house is just north of the hamlet of Crockernwell, at the end of a long drive (the name probably means “lamb’s ford” and the drive does cross a stream). Originally a traditional cob and thatch Devon long-house, like the house at Gorwyn its medieval core was enlarged and improved by extensions both in the 1500s and later. It has a number of architecturally interesting features, including wood-panelling, the old spit-rack over the hall fire-place and its old spice cupboard. Pevsner9 describes it as “a large and important farmstead showing Devon vernacular at its 15th-17th century best”. The Lambert Gorwyns tended to describe it as a “manor-house”, and it does indeed seems to have been the most important house in Little Lampford. Like Gorwyn, it is a Grade II* listed building, one of only three farms in Cheriton Bishop to be so listed. It was, however, extensively remodelled in the 1980s to insert modern facilities like bathrooms, and it is now quite hard to imagine how it must originally have been. Like Gorwyn, it is now close to the A30 dual carriageway and suffers sadly from vehicle noise.

Various spellings were used for both the big and the small Manor, including Lantford, Lamford and Lamsford. From the 16th and early 19th century, Lampford seems to have been the most common usage for the property. But the spelling “Lamberte” appears to have been used in a deed of 1625, and thereafter Lambert appears periodically as one of the variants. For some reason, this was the variant normally used by the family for their name, even though they often continued to refer to the property as Lampford. For instance, when the widow of the mid-18th century John Lambert alias Gorwyn died in 1797, she was described in the parish register as ‘Mary Lambert of Lampford’. When her son John Lambert Gorwyn acquired the manorial rights for Lambert from the Hole family in 1800 , the deed also used the spelling Lampford, although noting that Richard Hole, in his will of 1793, used the form Lambert. By the middle of the 19th century, however, Lambert appears to have become firmly established as the correct spelling for the property as well as the family.

The house at Lambert

The family’s first use of the name Lambert

The first recorded use of the name Lambert is on the 1598 map of Crediton mentioned above showing “Wm. Lambford” as the owner of Bradleigh. Probably William’s branch began using the name Lambert to distinguish themselves from the rather rackety Gorvens at Gorwyn, or perhaps for snobbish reasons because of the manorial connotations of their new property. It seems, however, that the use of the name was only sporadic, probably depending largely on the whim of the current owner of Lambert. There is a list of deeds relating to Lambert in the National Archives10 that allows one to trace the ownership of Lambert down the generations after William Gorwyne with a reasonable degree of certainty. It seems to have passed from him to his son or grandson John. In 1615 the Cheriton Bishop register of baptisms records the baptism of William, the son of John Gorven. Inserted above the line after the name John Gorven has been written something that might be “als [ie alias] Lambert”. Next, a list of manorial rents in the Devon Record Office records that in 1644, “John Gorwin alias Lampford” was paying rent to the Lord of the Manor of Lampford. So it seems that, although William Gorwyne’s family began early in the late 1500s to use the name Lambert, they also continued to use the name Gorwyn. It was not for another 150 years that the style “Lambert Gorwyn” became generally adopted by members of the family.

Gorvens and Gorwyns

It was also during the 1600s that the spelling ‘Gorwyn’ or ‘Gorwin’ or ‘Gorwyne’ began more generally to replace the earlier ‘Gorven’ for both the farm and the family, although the spelling did not really settle down until the end of the 18th century, with the name of the same person sometimes being spelt differently in the parish records from one year to the next11. There is, however, some evidence that, during the 1600s, the branch of the family living at the ancestral farm kept to the spelling ‘Gorven’, whereas William’s branch changed to ‘Gorwyn’. The Gorvens appear to have slipped gradually down the social scale, having had to give up the property at Gorwyn to pay their debts, and by the 18th and 19th centuries the people still using the spelling Gorven appear to be in fairly menial positions12. They seem finally to have petered out and to have had no descendants in the male line. Our ancestors the “Gorwyns”, however, continued on the up and up, accumulating more and more property.

Notes

1 National Archives ref: C2/ChasI/G38/61.

2 National Archives ref: C10/4/80

3 National Archives ref: C1/1196/42-4 (1544-1551): John Bradlegh v. Peter Gorven and Alice his wife and John Trueman: detention of deeds relating to lands in Crediton entailed by Thomas Bradlegh, grandfather of William and Alice.

4 Stone v. Gorwyn, National Archives ref: C12/1319/18 and C12/1529/14.

5 Devon Record Office, ref 6372.

6 Stone v. Gorwyn.

7 The inquisition post-mortem is mentioned in Stone v. Gorwyn, but has not survived.

8 In 1657, Edward Wise of Sydenham sold the “manor of Lampford” to Nathaniel Risdon of Spreyton, although by that time what he was selling was probably no more than the right to certain manorial rents out of properties in the manor (deed in the Devon Record Office, ref. 158M/T752). The Risdon interest in the Manor descended by inheritance to the Hole family; they sold it to John Lambert Gorwyn of Lambert in 1800.

9 Devon, in the series The Buildings of England, second edition.

10 Stone v. Gorwyn.

11 The first uses of the spelling ‘Gorwyn’ were in the mid-1500s, when the names of a branch of the family in Drewsteignton are thus spelt.

12 Apart from a family of Gorvens living in Cheriton Bishop, there was according to the census a working class family called Gorwyn or Gorrin in Crediton in the mid-19th century, and in 1798 Thomas Cobley of Colebrooke took an apprentice called James Gorwyn,as a farmworker. These were possibly also descendants of the Gorvens who had slid down the social scale.

GO TO NEXT CHAPTER BACK TO LIST OF CONTENTS