8. GEORGE LAMBERT M.P. (George IV) 1866-1958 AND FAMILY

- Early years

- 1891 election campaign

- Subsequent career

- George Lambert V (1909-1989)

Early years

George III’s only son, the fourth of the Georges of Spreyton, became the most famous of the Lambert-Gorwyn tribe on account of his long and distinguished political career. One of the many quarrels that his father George III had engaged in was with the churchwardens of Spreyton church over the renewal of the pews. He had offered to pay for new pews. He then fell ill, and during his illness the churchwardens installed not pews but chairs. This apparently irritated him so much that when they presented him with the bill he refused to pay and only did so after legal proceedings were taken against him. As a result, he swore never to set foot in the church again. He turned to the local Methodist chapel, taking his family with him, thus introducing his son, the future MP, to the non-conformist tradition of Liberalism and oratory that played such an important part in George IV’s political career. So it can be said that his son’s political career was the result of a squabble over pews.

George Lambert IV was briefly educated at the then grammar school at North Tawton, but was withdrawn by his father when he was 15 to help run the farm and to be given what his father considered a more practical education. This included being sent to work with the local horse-dealer so that he could learn to be “sharp”. Even before he left school, he was being to work; a surviving list of manorial rents due in 1879 shows that they were collected by “George Lambert junior”, then aged only 131. He seems quickly to have become an adept on the agricultural front, and when his father died in 1885, the 19-year-old George seems to have stepped effortlessly into his shoes.

In the following year, when the owners of the neighbouring farm of Spreytonwood failed to find a new tenant, they pressed George to take the lease of it. Spreytonwood is a large farm (over 300 acres) and it says a lot for his precocious ability as a farmer that despite his age they saw him as the best person to take it over. It says a lot also for George’s acumen that he managed to negotiate the rent down from £145 to £120. The lawyer who was handling the matter for the owners was obviously amazed to discover that he was dealing with a minor and pointed out with some embarrassment that George’s mother would have to sign the lease on his behalf2. George appears also to have taken in hand the previously tenanted farm of Falkedon. With the addition of Spreytonwood, he more than doubled the acreage that he was farming to some 700-800 acres – a very large area for that part of Devon. The farm diaries3 that have survived show that the number of men permanently employed on the farm went up from three in the early 1880s to nine in 1887. By 1891, when he was 25, George was being described in the press as one of the most practical farmers in the agricultural county of Devon.

The young George Lambert (on the left) in his farmyard at Coffins

The young George also seems to have been drawn early on into local politics. By the time he was 21, he was on the Okehampton Board of Guardians, the elected body that had by then taken over the administration of the poor law. When Devon County Council was created in 1888, he was according to a press report4 invited to put his name forward for election, but then withdrew so that “another well-known county gentleman could be returned unopposed”. The feeling was so strong among the farmers, however, that he should be their representative that a requisition signed by nearly a half of all the electors was presented to him, inviting him to stand, and he was returned by a decisive majority in February 1889. When the youthful councillor first arrived to take up his seat, he was turned away by the doorman, who told him firmly that “boys” were not allowed in. He remained on the County Council (from 1912 as a County Alderman) continuously for 63 years.

National politics followed hard behind. He was already active in his local Liberal Party, and when the neighbouring South Molton constituency needed a new Liberal candidate, his name seems to have entered quickly into the frame. South Molton was a large, straggling constituency of 81 parishes, going from South Molton and Torrington in the North to Newton St Cyres, and Crediton in the South. It did not at that time include Spreyton, George’s home village, but the neighbouring villages of North Tawton and Bow were both in the constituency. It had been a Liberal seat under Lord Lymington, the son of the Earl of Portsmouth, a respected local magnate. But in the 1886 election, Lord Lymington had broken away from the Liberal Party to stand as a Liberal Unionist – one of the small bunch of Liberals who opposed home rule for Ireland and had thrown in their lot with the Tories (during the 1891 election campaign, George was to refer to them as “simply the aristocratic element of the real Liberal party, who conferred no practical benefit on the country”). An official Home Rule Liberal candidate had stood against Lymington, but had failed to make much headway, and Lymington got in by the large majority of 1,689 (out of some 6,400 voters). While Lymington himself does not seem to have been particularly popular, his family were held in great respect, and that no doubt ensured his election whatever his colours.

1891 election campaign

By 1890, the prospect of a general election was looming, and the official Home Rule Liberals began to look around for another candidate. It is not clear who decided that the young George Lambert was their man. He was approached in May 1890 by representatives of the South Molton Liberal Executive Committee. His first reaction was to refuse (he seems to have made rather a habit of these shows of reluctance). But the Party representatives, nothing daunted, organised a petition calling on him to stand5. The first that he heard of this, he later told the Executive, was when he was stopping in a distant part of the county, and a friend, whose politics were opposed to his, mentioned it to him, “to his utmost surprise”. The petition or requisition was signed by some 1800 people, signatories coming from almost every parish in the constituency (to put this figure in context, there were at that time some 7,000 voters on the electoral register). He allowed himself to be persuaded and was duly adopted as the official parliamentary candidate for the Liberal Party on 13 February 1891, when he was not yet 25.

The following year, the Earl of Portsmouth died and Lord Lymington succeeded to his title, which meant that a by-election was needed. To stand against George as the “Liberal Unionist” candidate, the Unionists put up a man called Charles Buller, a remote relation of General Sir Redvers Buller of Crediton (a hero of the 1879 Anglo-Zulu war). They obviously hoped that this relationship with a well-known family of Devon landowners would stand their candidate in good stead with the electors. Otherwise, however, he had little connection with Devon and lived far away. He was supported by the Tories and there were no other candidates.

George’s policies, other than home rule for Ireland, included one-man one-vote (only men paying at least £10 in annual rent or owning land worth at least £10 were at that time allowed to vote); greater powers for local government, including elected parish councils with significant powers; less church control of schools and more religious freedom (he attacked some church schools for teaching that non-Conformists were heretics and said he wanted marriages allowed in non-conformist churches); old age pensions paid through national insurance (a cause he seems to have felt particularly strongly about, having seen the dread with which elderly farm labourers regarded the poor-house, often their only future once too old or incapacitated to work); greater security for tenant farmers, including compensation from the landlord at the end of the tenancy for any improvements that the tenant had made; general permission for tenants to take ground-game such as rabbits on their land; and such agricultural issues as the purity of manure (suggesting that there should be a testing procedure available to farmers).

Those were the days when almost all political campaigning had to be done face-to-face. After his adoption as a candidate, George made a practice of speaking at “Ordinaries”, the communal lunches at local hostelries to which the farmers and dealers retired after the morning cattle markets that took place regularly in a number of parishes in the constituency. In 1891, when the by-election was declared, both candidates began a gruelling round of parishes to address the local electorate. In those pre-television days, these meeting provided rare entertainment for the villagers, who turned out in force. The meetings were normally packed with often a couple of hundred people (more than 1,000 turned up to a meeting in Crediton). They were lively affairs, with the audience keeping up a running commentary throughout and frequently interrupting the speaker with questions.

George was clearly an enthusiastic and at times a rabble-rousing orator, often speaking at greater length (up to an hour) than a political audience would tolerate today, and he dealt well with questioners and hecklers. But he was far from polished in his language, and the Tory press made fun of him by quoting verbatim his muddled sentences and mangled syntax in much the same way as today’s press mocks John Prescott or certain American politicians. His age and lack of experience were also an obvious target for his opponents.

It became a famous by-election, followed by the national as well as the local press as a crucial test of the relative strengths of the Unionists and Home Rulers. Both sides brought in heavyweight politicians from elsewhere (including from Ireland) to speak for their man. Although home rule was the official difference between the two parties, the contest was more generally seen in the constituency as between the aristocracy – and to some extent the Church of England – represented by the Unionists; and the tenant farmers and farm labourers represented by the official Liberals. MPs in rural constituencies, both Liberal and Tory, were traditionally scions of local landowning families, as Lord Lymington had been. George Lambert, who described himself as the “tenant farmers and industrial classes candidate”, was most unusual in coming from a yeoman farming family with only tenuous claims to be gentry. Buller came from an altogether grander background, and was heavily supported by the big local landlords, who undoubtedly regarded Lambert as an unfortunate upstart

At least some Church of England clergy also came out overtly against Lambert, a couple even refusing to let him use their local school-room (the only meeting-place in most villages) for his political meetings during the campaign. One of these was the Rector of King’s Nympton, who allowed Buller to use the schoolroom but wrote Lambert a letter explaining that he was not prepared to let George do so, as the school was for educational principles only, and the “revolutionary principles broadly hinted at” in Lambert’s printed election address were excluded from such principles. The Non-Conformist movement, however, was largely behind Lambert. They felt a certain sympathy with the Catholics of Ireland, whom they saw as another minority oppressed by the established church. A group of Non-Conformist Ministers from local parishes even got together to publish an “appeal” in the Western Times. Referring to the “no popery” cries that had been raised by the Unionists, it expressed the earnest hope that the Non-Conformists of South Molton would not suffer themselves to be imposed upon by appeals to the spirit of “unreasoning fanaticism” and would mark their confidence in Mr Lambert, as a supporter of Mr Gladstone’s message of conciliation and goodwill.

The Liberals made much of the fact that practical farmers (as opposed to large landowners) were at that point unrepresented in Parliament. There is some indication that some normally Tory farmers supported Lambert because he was seen as someone who really understood their problems. For instance, a group of some 250 farmers “both Conservative and Liberal in politics”, including some outside the constituency, signed a letter to the press supporting him on those grounds. The signatories included his remote cousin William Lambert-Gorwyn of Hittisleigh. Many Tory farmers probably voted for him as they were personally acquainted with him.

The poll was an exceptionally heavy one, with 7,270 voters out of a total electorate of 7,720 (94%), despite the fact that it was on a rainy Friday, a market day when many farmers were making their way to the markets at Barnstaple and Exeter. There were polling stations in only about every three or four of the smaller parishes, so voters had up to four or five miles to travel. Lambert convincingly overturned the previous Unionist majority, receiving 58% of the vote, a majority of 1,212 – a figure that some ladies of the parish subsequently made into an embroidered picture still in the possession of his descendants. The Liberals had been expecting victory, but only by some 400-600 votes, so it was a spectacular result. Only a year later, there came a general election and George found himself again on the hustings, this time winning by an even bigger majority. From then on (except for one election in the 1920s) the seat was safely his.

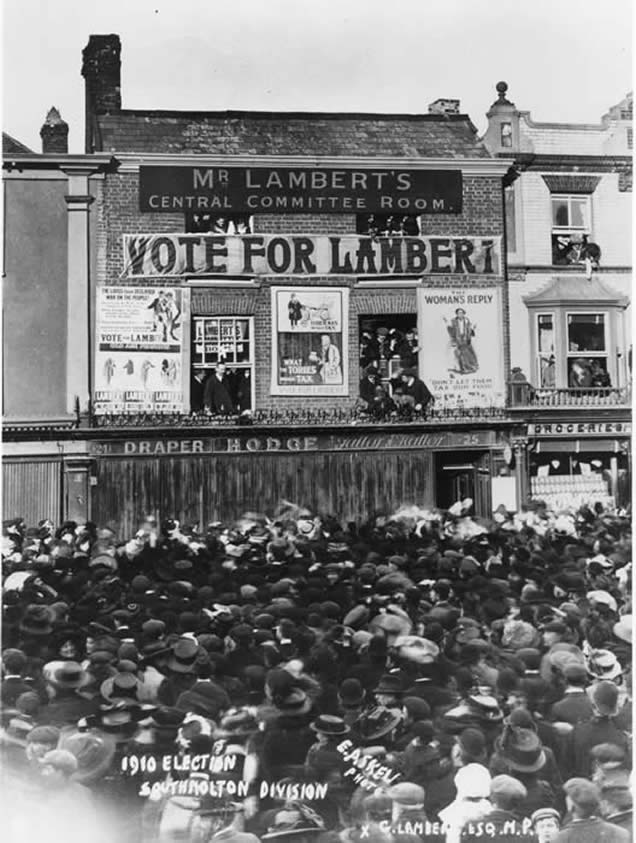

George Lambert at the window of his campaign headquarters in South Molton greeting his supporters after

winning one of the two 1910 elections.

George Lambert seems to have established from the beginning of his time as an MP a reputation for approachability and energetic pursuit of local concerns. He quickly became known as “Farmer George” or “Our George” (pronounced “Our Jarge), a nickname he kept for the rest of his life. An 1891 press report described him as “a little above medium height, fair and good-looking; thoroughly conversant with all the public questions of the day; [with] a ready facility of expression as well as directness of style and answers questions put to him with a charming frankness”. He was also said to be “a capital sportsman and an excellent shot”. In his later years, he gave up shooting in favour of golf, and one of the achievements for which he received the most congratulatory letters was when he beat the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) to win the Parliamentary golf handicap, despite being in his 60s and some 20 years older than his opponent. No doubt the very fact that he had dared to risk the lèse-majesté of beating the heir to the throne added to his kudos.

Subsequent career

When George arrived in London to take up his seat in the House of Commons, Gladstone was the Prime Minister, and George subsequently became the last man alive to have served in the same Parliament as Gladstone. He seems quickly to have gained a reputation as an active and able young man, and in 1905 was made a junior Minister, serving as Civil Lord of the Admiralty under Winston Churchill (who was at that time a Liberal and First Lord of the Admiralty, the then name for the Cabinet Minister in charge of the Navy). It was a surprising appointment, as George knew nothing about naval affairs (the political commentators of the time described him as “a farmer at sea”). But he seems to have tackled his brief enthusiastically.

In 1912 George was made a Privy Councillor and thus became the Right Honourable George Lambert. The rank of Privy Councillor goes automatically with being a Cabinet Minister, but is not that usual for more junior Ministers. This elevation of a local son was a subject of much pride among his Devon constituents. Typical comments in the congratulatory letters that he received from all over Devon were: “All Devonians are glad at the well-deserved honour”; and “It was particularly pleasing on opening the paper yesterday to see that your strict devotion to duty and your unswerving Liberalism is having its reward”. Liberal passions still ran high and one comment was “The Tories are down in the mouth over it; it is not what they desired”. Several older correspondents recalled their memories of the by-election of 1891, that famous Liberal victory still obviously casting a glow among its veterans. There was much reference to his long service to the constituency, although as it turned out he was not then even half way through his time as the local MP, and to expectations of further honours.

George as a young MP |

George in his Privy Councillor uniform |

George remained Civil Lord until 1915, an adequate rather than an outstanding Minister (Asquith referred to him in a letter to Venetia Stanley as being not very competent). He was a strong supporter of Admiral Lord Fisher, who was sacked in a row over naval strategy in the middle of the First World War. Although the then Prime Minister Lloyd George offered him another post in 1915 as a junior Minister for Agriculture (well-suited to his talents), he turned this down because Lloyd George refused to reinstate Fisher. From then on he became a notoriously independent-minded back-bencher. The Dictionary of National Biography describes him as “not given to subtlety of speech or opinion, but he was downright, steadfast and incorruptible: a force to be reckoned with by the party leaders”. He was chairman of the Parliamentary Liberal Party from 1919-21 and was active in trying to hold together the increasingly fissiparous Party, although ultimately to little avail. His economics were old-fashioned; perhaps unsurprisingly for some one who was the product of some 25 generations of independent-minded yeoman farmers, he remained all his life strongly opposed to state intervention, which he saw as sapping the natural enterprise of the Englishman. He remained in the House of Commons, with one gap in the 1920s, until 1945, when he was created Viscount Lambert of South Molton in Winston Churchill’s dissolution honours. For his coat of arms he chose a variety of agricultural and Devonian symbols. His shield is decorated with a fleece and two sheaves of corn. It is surmounted by a green hill on which there stands “an apple tree fructed proper” (i.e. with a full load of fruit). For his bearers, in the absence of any specific Devonian birds he chose two Cornish choughs. And his motto was “The good earth provides”.

Throughout his political career, he remained immensely popular in Devon. Letters addressed to “George Lambert, Devon”, invariably reached him. He was Patron or President of almost every Devon society. He also founded the Seale-Hayne Agricultural College6, an institution that gained an excellent reputation (it was incorporated into Plymouth University at the end of the 20th century and now no longer exists).

George married Barbara Stavers rather late in life (he was almost 40) and apparently to the surprise of his constituents, who had come to regard him as a confirmed bachelor. On her mother’s side she was of Devonian extraction – her Devon ancestors were called Curson and came from South Tawton, where there are various memorials to them in the church and churchyard. On her father’s side, however, she came from a Northumberland sea-faring family who captained their own ships – mostly coalers operating out of Newcastle. George and Barbara had two daughters and two sons.

Barbara Lambert with her two daughters Margaret and Grace

George Lambert (top back) with his four children and a chauffeur in the family Model T Ford

George Lambert shortly before his death at the age of 91

One of his daughters, Margaret Lambert CMG (1906-1995), went to Oxford at a time when this was quite unusual for girls and subsequently became a historian specialising in the diplomatic history of the interwar period (her doctoral thesis was on the Saar, the part of Germany occupied by France after the First World War). After the Second World War she was invited by the Foreign Office to edit for publication the archives that the Allies had seized from the Nazi Foreign Ministry. This was a work of some delicacy, as the archives included some somewhat damning accounts of conversations that German diplomats had had with Edward VIII (later the Duke of Windsor) before the war. Margaret and her historian colleagues were determined that these should be published and finally had an interview with the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, to make this clear, the result of which Margaret recorded in a letter. Margaret also wrote books with her partner Enid Marx on English popular art.

George Lambert V

Table 4 shows the immediate descendants of George Lambert IV (there are none now in the male line). George Lambert’s elder son George (George V) was a stockbroker who joined the Army in the Second World War, from which he emerged with the rank of Colonel. He stood for and won the seat of his father in the 1945 election (the constituency boundaries had by then been changed and the constituency was called Torrington). George V continued as the M.P. for Torrington until 1958 when the death of his father at the age of 91 meant that he inherited the Viscountcy and had to leave the House of Commons for the House of Lords (at that time it was impossible to renounce peerages, although the young Tony Benn did suggest to George V that he should try to use an obscure legal advice to do so). Tragically, George V’s son, the last of the Georges, was killed in a car accident as a young man, bringing to an end the unbroken line of Georges that had begun over 200 years earlier. His death also ended the Lambert presence in Spreyton, as after his death Coffins and the estate that went with it were sold.

Notes

1 The list of rents collected by George Lambert junior in 1879 is among the Lambert estate papers in the Devon Record Office.

2 1886 correspondence between the Rev. Robert Hole of North Tawton and George Lambert. Another indication of George’s ability and ambition comes from the Coffins farm diaries that survive from the 1880s.

3 Farm diaries, presumably kept by the foreman on the farm, survive for 1883, 1885, 1887 and 1888. They show what was being done each day on the farm by each employee.

4 North Devon Journal, 19.11.1891.

5 This survives and is in the Lambert political papers in the Devon Record Office.

6 Charles Seale-Hayne, the rich Liberal MP for a neighbouring constituency when George Lambert was first elected, had befriended the young MP and let him lodge at his house in London. When Seale-Hayne died, he left his estate to be used for agricultural education and made George his executor.