SIENA: CHURCHES |

The churches listed below are the main ones of particular artistic or historical interest, but they constitute only a tiny fraction of the many churches in Siena, most of which are very ancient.

By far the most important and spectacular church is the Duomo or Cathedral. Both the two main preaching orders of friars, the Domenicans and Franciscans, also built massive Gothic churches in Siena, San Domenico and San Francesco, to accommodate the large audiences that they hoped to attract for their preaching. Both are well worth a visit. Several other religious orders had monasteries or convents here, often with large and beautiful churches filled with works of art. Then there are a large number of smaller churches. These include the contrada churches, where members of a contrada go for baptisms, weddings and funerals, and where the contrada’s horse is blessed before the Palio. Most of the latter are very small and usually shut except for services, so they are not covered in this guide.

- Duomo

Siena’s great stripy cathedral with its Baptistery, Crypt and Bishop's Palace.

- San Cristoforo

A tiny church off the main street, said to be Siena’s oldest

- San Domenico

The Dominican church of Siena, containing relics and a contemporary portrait of St Catherine of Siena. One of the most important churches. Near the Fortezza.

- San Francesco

A huge Gothic church with Lorenzetti frescoes. A visit can be combined with one to the Oratorio San Bernardino next to the church.

- Santa Maria in Portico a Fontegiusta

A small church near Porta Camollia with a delightful Renaissance interior.

- Santa Maria in Provenzano

A stunning baroque façade and a miraculous statue of the Madonna

- Santa Maria dei Servi and the Porta Romana

An impressive Gothic church with interesting paintings

- San Martino and the Loggia del Papa

A church and an arcade near the Piazza del Campo; there is a good painting by Beccafumi inside.

- San Niccolò al Carmine

and the Arco delle Due Porte

A smallish out-of-the-way Church with a magnificent Beccafumi painting.

- San Pietro alla Magione

A tiny Romanesque church near Porta Camollia that belonged to the Knights Templar and the Knights of Malta.

- Santo Spirito and the Pispini fountain and gate

A mainly classical church with good paintings by Sodoma; a pretty nearby fountain and one of Siena's massive fortified gates.

- Church and Convent of the Osservanza

A large red brick Renaissance church overlooking Siena from a hill on the northern edge of the city, with good della Robbia terracottas.

Although the Duomo is in full use as Siena’s cathedral, it is also treated as a tourist attraction and entry is by ticket, which can be purchased from the ticket office by the Museum of the OPA. Separate tickets are needed for the Baptistery and Crypt, even though they are part of the Duomo. A three-day combined ticket that allows you entry to the Baptistery, Crypt, OPA museum and Oratorio San Bernardino (the latter not always open) is very good value. Within the Duomo there are wooden barriers herding tourists around in a circuit and away from the famous pavements. Duomo, Crypt and Baptistery are usually open from 10.30, but entry to the Duomo depends on what religious services are taking place. Go early to avoid the masses.

Duomo (from the Latin domus or house, meaning House of God)

This is one of Italy's great cathedrals, but as a building curiously unsatisfactory; indeed to many hideously ugly. Ruskin, in the 1880s, described it as "every way absurd - over-cut, overstriped, over-crocketed, over-gabled, a piece of costly confectionary, and faithless vanity". William Beckford, in the 18th century, wrote of his visit to Siena:

"Here my duty of course was to see the cathedral, and I got up much earlier than I wished in order to perform it. I wonder that our holy ancestors did not choose a mountain at once, scrape it into tabernacles, and chisel it into scripture stories. It would have cost them almost as little trouble as the building in question, which may certainly be esteemed a masterpiece of ridiculous taste and elaborate absurdity. The front, encrusted with alabaster, is worked into a million of fretted arches and puzzling ornaments. There are statues without number, and relievos without end or meaning. The church within is all of black and white marble alternately......I hardly knew which was the nave, or which the cross-aisle, of this singular edifice, so perfect is the confusion of its parts......In every corner of the place some chapel or other offends or astonishes you."

So you will not be alone if you find the whole thing all too much. Built between 1150 and 1330, the cathedral began as a Romanesque building, gradually turning to Gothic as fashion evolved during the long years of its construction. It is so surrounded by buildings that the outside is almost impossible to see properly from nearby - except for the hideously over-decorated facade, finished with garish 19th century mosaics, and the beautiful front of the Baptistry at the other end. For a general view of the dome, elegant campanile and lightly striped marble walls, it is best to go to another of Siena's hills to glimpse the cathedral across the valley - the view from behind San Domenico is particularly good.

The Siena Duomo (the word comes from the Latin domus or house, and stands for House of God) had barely been completed before the Sienese, afraid that the Duomo then being built in Florence would outshine theirs, decided (in 1339) to build a whole new and much bigger cathedral, incorporating the present one as its transept. The beginnings of the new nave can still be seen on the right hand side of the cathedral - the Cathedral Museum (Museo del OPA) is built into one of its side aisles, and some beautiful marble tracery shows what a fine work it might have been. But the Black Death of 1348 struck before it was completed and left Siena so shaken and impoverished that this grand design was never taken forward. The huge red brick archway (Facciatone) that would have been the main entrance has a stairway inside it and can be climbed from the Cathedral Museum . The road down the side of the Duomo leads through another arch that would have been a side door; the outside of this arch has one of the most perfect and beautiful Gothic doorways in Italy.

Inside the Duomo, the slim, sparse and elegant stripes of the external walls are replaced by heavy horizontal zebra stripes on every surface. The effect is dark, over-powering and even downright ugly. To enjoy the interior, one must ignore the general effect and concentrate on the detail - as it is more full of wonderful things than almost any other church in Italy, and needs several visits to appreciate. The three best things in it are the Piccolomini Library, the amazingly carved 13th century Pulpit, and the Pavements - but there are many, many more works of art of a quality that people would come miles to view in any English church, and more in the Baptistery below the Duomo. Most guidebooks give the Duomo fairly full coverage, so this concentrates on the pavements, the Piccolomini Library, the newly opened crypt and the Baptistery.

The Pavements

Almost the entire floor of the Duomo is covered in pictures in inlaid stone, designed by the leading artists of the period between 1370 and 1550. Until recently, as many of the 56 separate scenes are so worn and susceptible to further damage, they were permanently covered in pieces of hardboard and could not be seen. However, since theDuomo has been turned into a museum during the most of the pavements are uncovered; and visitors are allowed to walk between them, and also behind the altar to see the pictures in inlaid wood above the stalls. So well worth a visit if you are there then.

The scenes are extremely varied, ranging from pagan sybils along the side aisles to great Old Testament battles and New Testament dramas. Each of the sybils is different – an elderly one from Cumaea; a black one from Libya; a learned one with a book from the Hellespont (beside whom a wolf and a lion endearingly but sheepishly shake hands).

Detail from the Hellespontine Sybil by Neroccio di Bartolomeo de’ Landi (1447-1500).

In the main aisle, the second from the main door shows Siena’s (and Rome’s) symbol of a wolf suckling Romulus and Remus (Remus’s son is supposed to have founded Siena). In the middle of the main aisle, one of the best is the mysterious History of Fortune or Hill of Virtue designed by Pinturicchio. Fortune helps some wise men reach a rocky island. She holds the sail of a ship in one hand and anchors it to the earth with her foot. Above, Knowledge offers the palm of Victory to Socrates and Crates empties a casket of jewels – beautifully rendered, as is the detail of the plants and animals on the island.

Near the pulpit, there is a dramatic Massacre of the Innocents (a scene of which Sienese artists were horribly over-fond), with Herod actively directing operations from a throne on the left. It is by Matteo di Giovanni. Beyond, there is a good battle scene showing the liberation of Bethulia (besieged by Holofernes in the Book of Judith). In front of the main altar, difficult to see even when uncovered, is one of the best of several by Beccafumi, depicting the sacrifice of Isaac. Nearby, on the other side of the church, there is a striking death of Absalom, who had rebelled against his father David and was caught and killed by one of David’s supporters after his hair got entangled in a tree.

The Piccolomini Library

This a magical room off the left aisle (paying entry, except in August-September when there is a charge to visit the Duomo as a whole) decorated with brilliantly coloured frescoes. The room was intended as a library for the books of Siena’s most famous Pope, Aenea Silvio Piccolomini (Pius II) and frescoed in the early 1500s by Pinturicchio with scenes from the Pope’s life. The story begins in the fresco at the far end of the right hand wall and the frescoes then go round clockwise. They depict:

1. Piccolomini (on the horse) as a young man of about 18 from a noble but impecunious family, departing for the Council of Basle as the secretary to a Bishop. The party were driven ashore by a storm, shown in the background.

2. Piccolomini addressing James III of Scotland, to whom he had been sent on a secret mission in 1435 by his new master, a cardinal. A marvellously improbable picture of Scottish landscape. The weather was apparently not as good as appears in the painting; Piccolomini had to walk through ice and snow, on which he blamed the gout from which he suffered for the rest of his life. He is also alleged to have fathered an illegitimate child in Scotland.

3. Piccolomini being crowned as a poet by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III in Vienna. Piccolomini was by this time well established in diplomatic circles as a talented and useful young man. It was the period of opposing popes and anti-popes, and he first sided with the anti-pope, who had sent him on a mission to Vienna, where he had joined the service of the Holy Roman Emperor.

4. Piccolomini, an ambitious man who clearly knew where his best interests lay, then decided to switch papal sides. This served him well. In 1446 he was ordained a subdeacon, and here he is shown, only two years later, giving allegiance to the legitimate Pope and being consecrated as a bishop (the Church was the best way for a clever young man with no funds to achieve power and greatness).

5. (On the entrance wall) By 1450 Piccolomini had became Bishop of Siena, but continued his work as a diplomat and undertook the negotiations leading to the marriage of the Holy Roman Emperor to Eleanor of Aragon. Here he is presiding (in his Bishop’s mitre) over the meeting of the betrothed couple at the Camollia Gate of Siena. The pillar with the crests in the middle background still stands outside the Porta Camollia.

6. Continuing his rapid progression up the ecclesiastical ladder, Piccolomini is being ordained as a cardinal by Pope Calixtus III in 1456.

7. Piccolomini being crowned Pope Pius II in 1458, after being elected to succeed Calixtus III.

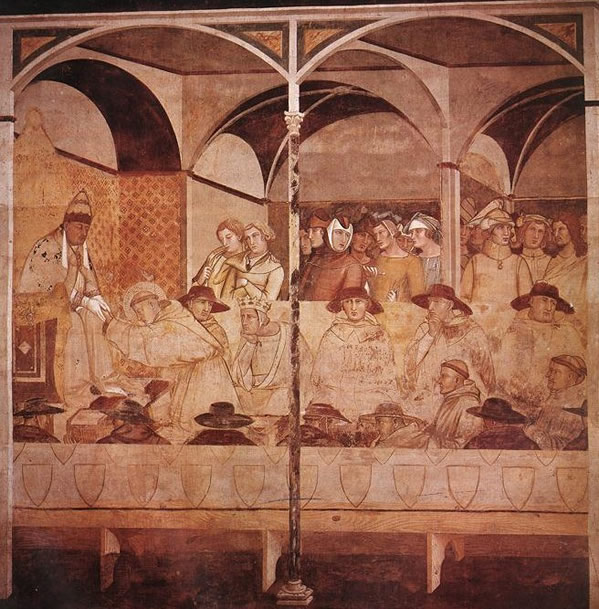

8. Pius II gathers together the Christian princes in a congress at Mantua to organise a crusade against the Turks (the central idea of his pontificate was to liberate all Europe from Turkish domination).

9. Pius II canonises St Catherine of Siena.

10. Pius II, who is by this time visibly ill, arrives in Ancona in 1464 to hasten preparations for the crusade. The Venetian fleet is arriving in the background. Unfortunately, the Christian princes did not share Pius’s enthusiasm for the crusade, and the Venetians, who were in it for the money, employed delaying tactics, no doubt hoping to extract a bigger payment for the use of their ships. The crusade never took off and Pius II died disheartened a couple of months later.

Piccolomini setting out on his adventures as a young man. The first fresco in the series Now an ageing Pope, waiting to launch a crusade. The last fresco in the series.

Each fresco is painted to show the scene through an arch with patterned sides, carefully drawn so that from whichever angle you regard the fresco the arch appears to have the correct perspective.

The Piccolomini crest was a crescent moon, and crescent moons pop up all over Siena. In the Library, the whole floor is covered in crescents.

The Crypt (separate ticket required)

Halfway down the steps beside the Duomo is a door into what is known as the Crypt (Cripta). In fact, it is no such thing; it was originally a series of ante-rooms to the Duomo used by pilgrims before the Baptistery was built. in the 1990s, while some rubble was being cleared out, it was discovered that these rooms were covered in pre-Duccio frescoes, dating from the early to mid 1200s. Unsurprisingly, they are in a bad state, but nevertheless retain their vivid colours and provide a fascinating glimpse of what an early medieval church was like, with every surface covered in paint – where there are no actual frescoes, the walls are painted to resemble marble, and even the pillars and their capitals are covered in bright colour.

Painted pillar in the Crypt

The best frescoes are in the main room, particularly the Crucifixion and the scene to the right of it showing the Virgin with the body of Christ, her hand round his neck and embracing his dead face. The end wall shows the Annunciation, Visitation and Nativity. On the back wall, there are further scenes from Old and New Testaments (Old above, New below). On another side wall there is a charming picture of the Holy Family, on their way to Egypt to escape Herod's massacre of the innocents, eating dates from a rather fanciful date-palm.This portrays a legend from an apocryphal gospel, also recorded in the Koran. According to the legend, the family stopped to rest under a date-palm, but it was too high for them to reach the fruits. The baby Jesus then performed his first miracle, by climbing down from the Virgin’s lap and ordering the palm-tree to bend down so that his mother could gather its fruits. Joseph is shown proudly pointing towards the miraculously bending palm-branch.

2005

The Baptistery (separate ticket needed)

The Baptistery (Battistero)

At the bottom of the steps, under the altar area of the Cathedral, is the Baptistery (Battistero). As so often in Italian cathedrals, it was built to impress and to emphasise the importance of baptism in the Christian religion. Its magnificent Gothic façade (built in 1355) would do justice to a moderate-sized church. Inside, almost every inch is covered with 15th century frescoes (heavily restored in the 19th century). There is a beautiful hexagonal font surrounded by gilded panels with reliefs illustrating the life of St John the Baptist:

- An angel announcing to St Zachary (the Baptist’s father) that he is to have a son – miraculously as his wife Elizabeth was barren;

- The birth of the Baptist;

- The Baptist preaching;

- The Baptist baptising Christ;

- The Baptist in prison;

- Herod’s feast at which Salome demanded the head of the Baptist.

The first and last are by Jacopo della Quercia and are particularly fine. The six statues above the panels represent the Virtues (Faith, Hope, Charity, Justice, Prudence and Fortitude). Two (Faith and Hope) are also by Donatello, who also created the four bronze angels.

2013

The Bishop's Palace (not visitable)

Next to the Cathedral is the handsome gothic residence of its Bishops.

The Bishop's Palace

**************************************************************************************************

San Cristofero

This little church, just opposite the Palazzo Tolomei, is worth just a brief glance if it is open. It is among the oldest in Siena and in the Middle Ages housed one of the governing councils of the city. It was renovated in the 18th and 19th centuries and is now a simple but elegant neo-classical building with a mainly baroque interior.

At the alter end of the right wall, there is a spirited painting of St George and the Dragon – the latter has cleverly coiled his tail round one of the saint’s horse’s legs. There is much argument among art historians as to the artist.

Above the main alter there is dramatic marble sculpture of the transit to heaven of St Benedict, helped on his way by two angels, in high baroque style By Giovanni Antonio Mazzuoli (1693).

2012.

*********************************************************************************

The Dominican church of Siena, containing relics and a contemporary portrait of St Catherine of Siena. One of the most important churches.

San Domenico, seen from across the valley

The Dominicans, like the Franciscans, liked to build huge barn-like one-aisled churches, and San Domenico is one such, an enormous structure of red brick, begun in the 13th century and altered at various times since, following disasters such as fires, an earthquake, and occupation by the Spanish soldiery in the 16th century. It is one of Siena's most prominent buildings, visible from odd spots all over the city.

Inside, on the right at the back, is the only portrait of St Catherine painted in her lifetime, or at any rate shortly after her death by someone who knew her, the artist Andrea Vanni (c. 1332-1413). She holds her symbol, a lily, and wears Dominican robes - she was a tertiary member of the Order. An unknown admirer is portrayed at the bottom of the painting.

In the middle of the right side of the church, the Chapel of St Catherine harbours her mummified head (looking surprisingly like her portrait) in an elegant marble tabernacle (carved by Giovanni di Stefano in 1496) over the altar. But it is the frescoes, mainly by Sodoma (1477-1549) that are the artistic glory of this chapel. On the left side of the altar, Sodoma shows St Catherine mystically swooning, and on the right in ecstasy, with various divine and holy personages watching from above. On the left wall of the chapel, St Catherine is interceding for the life of a young nun who has repented; on the right wall (this fresco is by Francesco Vanni, painted a bit later in 1596) she is exorcising a woman possessed by a devil.

Beyond St Catherine’s chapel, over the steps leading down to the crypt (usually closed), there is an attractive fragment of fresco attributed to the young Pietro Lorenzetti. Further on, there hangs a Nativity by Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502), set in a typically romantic ruin.

Most of the chapels in the transept contain little of interest. But in the first chapel to the right of the altar there is a colourful triptych by Matteo di Giovanni (1435-95), of the Madonna and Child with St Jerome (with his lion) and St John the Baptist. Both saints stand in a desert landscape, contrasting oddly with the sumptuous carpeted throne of the central panel, crowded with richly clothed angels bearing flaming torches.

A most attractive marble tabernacle and angels by Benedetto di Maiano (c. 1475) stands on the main altar, distressingly overwhelmed by the garish modern stained glass and huge golden candlesticks.

In the second chapel to the left of the main altar, on the right wall, the painting of St Barbara enthroned is well worth attention. This is also by Matteo di Giovanni, perhaps his greatest work, with lovely serene Botticelli-style faces. It is rare to see a mere saint given such prominent treatment. St Barbara carries her emblem, a tower. Note also the Adoration of the Magi above. Opposite, a Madonna Enthroned by the less distinguished Benvenuto di Giovanni (1436-1518) is in the old-fashioned gloomy Sienese style, all the figures - except the smiling Child - looking thoroughly anxious.

1980s

****************************************************************************

A huge Gothic church with Lorenzetti frescoes. The Oratorio San Bernardino next door is also well worth visiting (see museums section).

To get to San Francesco, turn off the Banchi di Sopra under the arch opposite the Luisa Spagnoli dress shop into the via dei Rossi. Go right down to the bottom and through another arch into the Piazza San Francesco. It can also be reached from the big car-park (with escalator) called San Francesco in the valley behind the church.

San Francesco

Originally, San Francesco was outside the walls of the city, and the arch at the bottom of via dei Rossi into the Piazza San Francesco, called Arco dei Frati Minori or Arch of the Minor Friars, was the gateway through the city walls. However, the 15th century Sienese Pope Pius II, whose parents were buried in San Francesco, was keen that the church should be brought within the city, and a new set of walls were built behind San Francesco.

Just before the arch into the Piazza San Francesco (one of Siena’s most attractive open spaces), it is worth glancing at the modern trompe-l’oeil marble statue of a topless woman at a window, on the left. Just below her, on the opposite side of the street and more or less under the via dei Rossi, lies the ancient Fonte di San Francesco, one of the old fountains that supplied Siena with water in the Middle Ages. It is now the contrada fountain of the Contrada of the Caterpillar (Bruco). More on fountains.

The Franciscans, who had a healthy rivalry with the Dominicans, usually built their churches bigger than anybody else’s, and San Francesco in Siena is no exception. It is a vast Gothic redbrick building, built in the 1200s and enlarged some hundred years later. It is largely unadorned on the outside, apart from the Gothic main door with rose window above. These are in fact 20th century pastiches; the façade was pulled down between the two world wars as it was thought to be dangerous and rebuilt. Originally, there were tiger stripes on the lower part of the façade and a quite different doorway, now to be seen inside the church.

The interior has been painted to resemble black and white marble as in the Duomo. The church was once far more garishly coloured inside, however, as can be seen from the traces of the original decoration in the chapels of the transept.There is not much to see in the huge bare nave, apart from some fragments of fresco and, on the left of the entrance, the magnificent renaissance main doorway by Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502) which adorned the façade before its rebuilding. Rather inconguously, it now frames what is almost a trompe l’oeil modern painting of the modern holy man Padre Pio. A number of large and not particularly distinguished oil paintings have been mounted on ugly iron frames in front of the side chapels instead of being hung in the alcoves of the chapels as was surely meant.

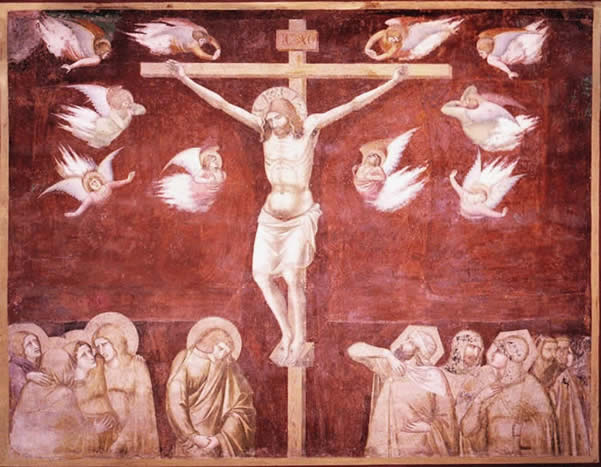

The works of real interest are the frescoes by the Lorenzetti brothers in the chapels to the left of the high altar, all that survives of what must have been an extraordinary array of wall decoration. The chapel immediately on the left of the high alter (light switch just inside the chapel, on the right) contains an intensely tragic crucifixion by Pietro Lorenzetti; even the angels in the sky have tortured faces and attitudes and it is one of the most moving paintings in Siena.

In the third chapel to the left there are two frescoes by Pietro’s brother Ambrogio, unfortunately less well preserved (light switch again just inside the chapel on the right). That on the right shows St Louis of Toulouse taking leave of Pope Boniface VIII, after he had renounced the throne of Sicily in favour of his brother Robert d’Anjou, seen here wearing his new crown and seeming far from pleased with it.

That on the left shows Franciscan friars being martyred in Morocco in 1227 while on an ill-fated mission to convert infidels. Note the oriental dress and features of some of those doing the martyring, more suitable to somewhere much further east, but no doubt Lorenzetti had never seen a Moroccan. All three frescoes were painted in the first half of the fourteenth century, and introduce a depiction of character that was then new to Sienese painting.

In the end chapel on the far left of the high altar there is a pleasant 14th century fresco on the side wall of the Virgin and Child by Jacopo di Mino, dating from 1400. But all except one of the paintings over the altars in the chapels are 19th century works in 14th century style. The exception is in the first chapel to the right of the altar, where there is a genuine 14th century Madonna and Child, unfortunately badly burnt in a fire in 1655. There is also some carving worth a look. On the steps to the chapel to the far right of the high altar there are two attractive 15th and 16th century tombstones, and two chapels further on, a fine 15th century sarcophagus of Cristoforo Felici, sculpted by Urbana da Cortona, is set high in the left hand wall .

On the opposite side of the right transept, a door leads into another chapel containing a frescoed Virgin and Child with Saints by the 14th century Lippo Vanni, painted to look like a polyptich in an ornate Gothic frame (unfortunately difficult to see because of the poor lighting). Off the left transept, opposite the chapels with the Lorenzettis, there is a large chapel with good pavement decoration, but frustratingly unlit and barred to visitors.

There are no fewer than three cloisters belonging to the monastery that used to be attached to the church. The first “Piccolomini Cloister” is accessible through a door next to the main entrance to the church. It is now occupied by the Law and Economics faculies of Siena University and is open during normal working hours. It was originally Gothic in style (two of the Gothic arches can be seen in the wall in the far corner), but was redone in elegant renaissance style in 1517 by a Piccolomini bishop – the Piccolomini crescent moon appears at the top of each arch. On the left side of the cloister there are steps up to the church with 18 identical crests (rather damaged) of the Tolomei family, another major Sienese family, commemorating 18 Tolomei men who were according to legend treacherously murdered by the rival Salimbeni family and are now buried underneath.

The second cloister, known as the Sansoni cloister, is reached through a door to the right of that leading to the Piccolomini cloister. It dates from the 15th century but has been knocked about quite a lot. Until recently, it was part of a barracks, but the soldiers have now moved elsewhere and it has also been taken over by the University. The third cloister is closed to the public. What remains of it can be glimpsed through a door on the left side of the nave of the church.

In 1730, a thief stole a precious receptacle containing some 350 consecrated hosts or communion wafers (particole), to the consternation of the population. The thief appears to have been interested only in the receptacle, as the hosts were found a month later stuffed in the offertory box of the neighbouring church of Santa Maria in Provenzano in a somewhat cobwebby state. A huge procession of clerics and townsfolk returned them to San Francesco, where they appear to have been put away (curiously, as consecrated hosts are seen as the body of Christ and are not normally kept for any time before being given in communion). Some 50 years later, somebody remembered them and examined them, to find that they were in a pristine state. This was seen as a miracle, and they were put safely away again. Since then, they have been examined at intervals, with some each time being tested for taste and consistency, and found still to be uncorrupted. What remains of the hosts after the testing etc. is still kept locked away in a chapel in San Francesco, being brought out for special occasions.

Revised 2003, 2012 and 2015.

***************************************************************************************************

Santa Maria in Provenzano

This church has one of the most attractive façades in Siena, built of clotted cream-coloured travertine in a baroque or mannerist style. It is set in quite a large piazza, enabling one to admire it with a fair degree of distance.

The church was consecrated in 1611 and contains a 14th century terracotta statue of the Virgin Mary (high above the alter in a glass case) which became associated with a number of miracles. It was in honour of this statue that the first July Palio in the Piazza del Campo was run in 1656, originating a tradition that continues to this day. At the time of the July Palio, the church is filled with the swirling flags of the contrade, and echoes to their drum rolls. On the evening before the Palio, the silk banner of the Palio is brought here and blessed. The next morning a solemn mass is said for all the contrade, and after the Palio members of the victorious contrada process to Santa Maria in Provenzano and sing a Te Deum of thanksgiving (for the August Palio, the Duomo is the church where all the ceremonies take place).

2012.

*****************************************************************************************************

SANTA MARIA DEI SERVI (properly San Clemente in Santa Maria dei Servi) and the PORTA ROMANA

An impressive Gothic church with interesting paintings.

To get to Santa Maria dei Servi from the Campo, take the via Porrione, and go straight on for a long way, past St Martino and on until a signed road forks to the left towards the church.

Santa Maria dei Servi, seen from the Palazzo Pubblico.

The campanile is 14th century and the church was also begun in that period, so the building is mostly Gothic – although as so often with churches it took a couple of hundred years to complete, and the facade remains unfinished to this day. It is the monastery church for the Servites who live next door. Inside it is handsome and spacious and its interesting paintings make it well worth a visit. The nave and transepts are covered in painted decoration; although probably dating from the 19th century, it gives an impression of what the church was like originally. When the lights are on, the joyous gaiety is almost impious to our eyes. When the lights are off, it is unfortunately quite hard to see the paintings.

Starting on the right at the back, between the first and second chapels, there is an attractive fragment of 14th century fresco of the Madonna rescuing the souls of children from Purgatory at the time of the Last Judgement.. In the second chapel on the left is an important painting of the Madonna and Child by the Florentine artist Coppo di Marcovaldo, one of the earliest Italian painters – he probably inspired both Guido da Siena and Duccio. He was captured by the Sienese at the battle of Monteaperti in 1260, and painted this picture as the price of his freedom. It is a marvellous example of Italian Byzantine, highly stylised with great emphasis on the folds of the rich and gorgeous robes, a perfectly balanced and elegant composition.

The church has not one but two extremely gory pictures of the Massacre of the Innocents, a subject of which Sienese painters were strangely fond. The first, in the fifth chapel on the right, is by Matteo di Giovanni and has recently been restored and lovingly regilded, rather for such a gruesome subject.The second is a fresco in a chapel of the right and is thought to be by Niccolo and Francesco di Segna with help from Pietro Lorenzetti. The agonised expressions of the mothers are powerfully rendered, and there is an interesting early example of the use of horses for crowd control. To the left is another possible Lorenzetti of St Agnes with her symbol of a lamb. Under this is the mummified body of the Blessed Francesco Patrizi, his bony hand stretched out.

In the end chapel of the right transept, there is a large and handsome 13th century crucifix of the Duccio school, as is the Madonna and Child over the door of the sacristy. Over the high altar there is a messy Coronation of the Virgin by Bernardino Fungai, and in the chapel on the far left of the altar there are yet more Lorenzetti frescoes, rather damaged, of the dance of Salome – note the head of St John the Baptist still steaming, or are they holy rays? – and of the ascension of St John the Evangelist. There is a pretty nativity above the altar of this chapel, with a hoopoe at the bottom, painted by Taddeo di Bartolo in 1404.

In the left transept, the Madonna della Misericordia is by Giovanni di Paolo, painted in 1471. The Madonna is looking rather constipated, but is elegant of shape, with curiously piercing eyes as she shelters mankind under her cloak. In the third chapel on the right, there is a Birth of the Virgin by Rutilio Manetti, with a great play of light and dark as befits a follower of Caravaggio.

Finally, before leaving, pause to admire the beautiful marble font near the door, dating from the 14th century.

The outer gate of the Porta Romana, as seen by those approaching the city.

To the south of Santa Maria dei Servi, the road to Rome goes out of the old city through the magnificent Porta Romana, one of the largest of Siena's defensive gates. It was built in the 14th century when a new outer wall was constructed around the south of the City after it expanded beyond the previous walls. Like most of Siena's gateways, it has a double gate. The outer gate is highly crenellated, machicolated and decorative; the more sober inner gate gives more of an impression of force and power, to remind those leaving of the might and wealth of the city. The Medicis, when Florence finally took over Siena, put their crest on the wall between the two gates, and above the inner door the space can still be seen where there was once an icon of the Madonna painted in 1417 by Taddeo di Bartolo to protect the city.

The outer gate as seen by those leaving the city down via Roma

1980s, revised 2004 and 2015 (Porta Romana).

**************************************************************************************************

SAN MARTINO AND THE LOGGE DEL PAPPA

A church and an arcade near the Piazza del Campo; there is a good painting by Beccafumi in the church.

They lie between the Banchi di Sotto and the Campo, about 50-100 yards down from the top of the Banchi di Sotto.

San Martino

San Martino

It was one of Siena's first churches, originally founded in the 8th century. The present building is much later - the sober classical facade dates from 1613, and the interior is mainly typical over-ornamented Italian baroque, heavy and not particularly attractive. But some bits of the interior are nevertheless worth a glance. Look for instance at the handsome and beautifully carved ensemble of statuary which makes up the main altar (the sculptor is the little known 17th century Giuseppe Mazzuoli). Look also at the two statues above the two side altars on either side of the main altar. That on the left, of the Virgin and Child, is also by Giuseppe Mazzuoli, whereas that on the left (of St Thomas of Villanueva) is by another and considerably less talented member of the Mazzuoli family. The two statues are illustrative of the good and bad sides of mannerism: the Virgin is alive and full of wonderful movement, whereas St Thomas is stiff and artificial, his attitudinising merely ridiculous.

Siena's most famous mannerist painter, Beccafumi, is represented by a beautifully coloured Nativity above the third altar on the left, typical of this painter with its interesting light effects but somewhat marred by the overly sentimental circling angels in the sky. Above the second altar on the right is a stiff and rather unpleasant Circumcision of Jesus by Guido Reni. The other paintings are undistinguished - although that above the third altar on the right is said to be by Guercino, it is in such an appalling state as not to be worth looking at.

The church has a 16th century cloister, rather damaged, which can be entered through a dark passage in the Via Porrione, just beyond the church.

Logge del Papa

This pretty loggia to the left of the church is another contribution to the city by Siena’s great renaissance patron, Pope Pius II Piccolomini (ppapa means Pope). It was built in the 1460s.

Logge del Papa

**************************************************************************************************

SAN NICCOLO AL CARMINE and the Arco delle Due Porte

A smallish out-of-the-way Church with a magnificent Beccafumi painting.

In the Pian dei Mantellini, San Niccolo al Carmine (also known as Santa Maria del Carmine) is the church of Siena's Carmelite monastery. Apart from the big handsome belltower, the red-brick building itself is undistinguished, but the paintings inside are worth a look if you are nearby (Pian dei Mantellini can be reached by going up via di Citta and then on – it turns first into via Stalloregio and then Pian dei Mantellini after going through one of Siena’s oldest gateways.There are number of ancient palazzi on the way).

On the way to the church, in via Stalloreggio on the left, high on the wall of a building on the corner of via del Castelvecchio, there is a tabernacle with a painting by Domenico Beccafumi, known as the “Madonna del Corvo”, or Madonna of the Crow. Legend has it that a crow brought the 1348 plague to Siena and that it was at this spot that it fell down dead. Unfortunately, it is difficult to see the painting through the protective glass.

By the gateway out into Pian dei Mantellini, there is another another 16th century tabernacle with Madonna and saints. Tabernacles of the Virgin were much favoured as the Sienese believed that she gave the city her special protection. The gateway, known as the Arco delle Due Porte (Arch of two doors) because it has double arches (one blocked for centuries), is in Siena’s oldest (11th century) wall built around the original nucleus of the City (as the ciy expanded, new outer walls had to be built). There is another tabernacle with Virgin and Child, allegedly the oldest in the city, outside the gateway, to the left of the blocked arch.

Arco delle Due Porte, the very ancient double gateway at the end of via Stalleregio

The entrance to San Niccolo al Carmine is on the side of the church. Over the altar opposite the entrance, there is a huge painting by Beccafumi, Siena's chief mannerist painter (14851551), of St Michael the Archangel pushing Lucifer and the rebellious angels down to hell, with a fierce-looking God the Father urging him on from above (there is another version of this scene in the Pinacoteca). It has Beccafumi’s usual good light effects, unfortunately difficult to appreciate in the gloom of the church.

To the right is an unfortunately damaged fresco of the Assumption with a choir of heavenly angels, attributed to the early 15th century artist Benedetto di Bindo. The angels are managing to hover in a most relaxed and convincing way, playing a variety of instruments, around the now obliterated figure of the Virgin being assumed into heaven. At the bottom left of the fresco, on one side of her empty tomb, St Lucy is carrying her eyes on a plate (one of the various attempts at martyring her involved her eyes being torn out, subsequently to be miraculously restored), and St Catherine of Alexandria stands on the other side. The figure in front of the tomb is Doubting Thomas, to whom according to legend the Virgin dropped her belt to prove that it was really her going up to heaven.

Detail from Benedetto di Bindo’s Assumption, showing the Virgin’s belt dropping into the hands

of the sceptical apostle Thomas

A door on the other side of the Beccafumi leads into the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament. Over the altar, there is a birth of the Virgin by Sodoma (painted about 1537), with a particularly large bevy of women fussing around the newly delivered mother. It has a handsome 16th century marble surround.

Back in the main church, next to the door into the chapel, there is 13th century byzantine-style Madonna and Child - the "Madonna dei Mantellini" inset into a larger and later painting by Francesco Vanni. The church also has a handsome 17th century polychrome marble main altar.

Next to the church, at No 44, is the old cloister of the convent. It is now part of the University, but still retains early 18th century frescoes of Carmelite life by Giuseppe Niccola Nasini.

1980s

********************************************************************************************************

SANTO SPIRITO & the PISPINI FOUNTAIN AND GATE

A mainly classical church with good paintings by Sodoma.

To reach this church, follow via Pantaneto, the continuation of the Banchi di Sotto, down the hill and turn left into the via Pispini, at the end of which you will see the red-brick façade of the church. It is just beyond the Pinacoteca picture gallery.

Santo Spirito

The church of Santo Spirito was originally built in the thirteenth century but its present interior is early sixteenth century and of typically elegant classical renaissance style, with symmetrical wide round arches and a large dome (not, however, a true dome architecturally speaking; as can be seen from the exterior, it is built inside a drum). Originally, the inside of the church probably had almost no decoration, but later in the baroque age stucco angels were attached to the sober classical lines, perching on ledges above the altar and providing an attractive asymmetry to the classical geometry of the church's bare architecture.

The church has a number of paintings of which the most interesting are the Sodoma pictures of saints above the altar in the first chapel on the right at the back of the church. The wishy-washy painting immediately above the altar in this chapel is not his, but most of the others show his vigorous style and were painted in 1530. On the left hand side of the chapel there is a good St Sebastian, and on the right is St Anthony the Abbot with his symbols of a bell on his wrist and a pig, a baby saddleback, at the bottom of the picture. At the top, St James of Compostella can be seen galloping over terrified Saracens. St James, one of the Apostles, died in 44 AD, many centuries before the Saracens appeared in Europe, but acquired a reputation in the early middle ages for returning in spirit form to help Christian armies fight the Saracens and Moors who were then invading the continent.

To the right of the main altar, behind a grill (light switch on the right) is an interesting crib scene with life-size figures of painted terracotta, allegedly by Ambrogio della Robbia (1554), one of the lesser members of the della Robbia clan. The statues have clearly been much repainted over the years, and the baby in particular looks far too romantic to have come from as far back as the sixteenth century. One of the shepherds is playing the bagpipes. (Bagpipes were according to one story introduced to Scotland by Italians from Cremona, who became the MacCrimmons, the hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod. In fact, bagpipes were probably a natural musical development in almost any society where animal skins were readily available.)

1980s, revised 2015.

The pretty Fontana dei Pispini used to stand in front of Santo Spirito, but has recently been moved a few hundred yards further down the via Pispini, where it now stands opposite the church of San Gaetano, the church of the Contrada of the Shell or Nicchio (see the large shell above the church door). This fountain dates back to at least the 1400s, but was transformed into its present shape in 1536. The Shell contrada has adopted it as its official contrada fountain.

Fontana dei Pispini

A little further down, the via Pispini reaches the Gate of the same name, the Porta dei Pispini. It is a huge double gate, one of Siena’s grandest, built in the 14th century in Siena’s outer ring of walls (which were constructed when the city expanded out of the previous walls).

Porta Pispini

There were real threats to Siena in those days and the walls are solid constructions. Outside of the Porta Pispini, along on the left is the Fortino di Porta Pispini, the sole survivor of seven bastions designed by the great 16th century Sienese architect Baldassare Peruzzi to strengthen the defensive capacity of the wall.

Fortino di Porta Pispini

2014

****************************************************************************************************

CHURCH & CONVENT of the OSSERVANZA

A large red brick renaissance church overlooking Siena from a hill on the north-eastern edge of the city, with good terracotta sculptures by Andrea della Robbia (1435-1525), perhaps the best of the family that popularised this particular art form in the 15th century.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

The convent (a term used in Italian also for male institutions) of the Osservanza was the home of San Bernardino until he left Siena in 1444 to die in L'Aquila (St Bernardino was a Franciscan friar who became an immensely popular preacher, the Billy Graham of his day). When he lived here, it was a small convent; but after his death, as his cult grew, a large church was erected to accommodate the many pilgrims. Since its construction between 1476 and 1490, it has suffered many changes. It was baroquified in the eighteenth century, debaroquified in the 1920s, bombed in 1944 and reconstructed after the last war. Despite all these vicissitudes, it is still an elegant example of the Renaissance. It also contains some marvellous Andrea della Robbia glazed terracotta sculptures, probably the best of his work to be found in Siena.

Inside the church, on each side of the main door, are tondos by Andrea della Robbia of St Louis and of St Bonaventura. On either side of the chancel arch at the other end of the church are wonderful statues of the Archangel Gabriel and of the Virgin Mary, both rendered in pure white, again crafted by Andrea della Robbia in around 1485. Note the charmingly natural pose of the Virgin.

The Annunciation: figure by Andrea della Robbia

And finally in the second chapel on the left is a magnificent della Robbia high-relief altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin with a predella below with scenes of her life, in imitation of a painting of the period. This was badly damaged during the wartime bombing, but has been lovingly reassembled and restored. Unfortunately, it is very badly lit, and visibility is not helped by a barrier wired to an alarm that prevents anybody from approaching too close to the side chapels.

Coronation of the Virgin by Andrea della Robbia. c.1485

There other sorts of good things in each of the other side chapels. Especially fine are the Madonna and Child by Sano di Pietro in the first chapel on the left (switch on the light); the 16th century group (in coloured terracotta by a Tuscan craftsman), mourning over the dead Christ in the second chapel on the right; and a triptych by Sano di Pietro in the third chapel on the right, with the Virgin between Saints Jerome and Bernardino (St Jerome, one of the great doctors or learned men of the church, as so often holds a book in which he is pretending to write, although the page already seems full; St Bernardino is instantly recognisable by his hollow-cheeked and toothless look). On the left wall of the same chapel there is a portrait of San Bernardino, painted by Pietro di Giovanni Ambrosi in 1444, the year that the saint died, so it may well have been from life. In the fourth chapel is a further triptych, this time with St Jerome (not even pretending to write this time) and St Ambrose, dated 1436 by an unknown painter now known after this painting as the ‘Master of the Osservanza’.

Virgin and Child between Saints Ambrose and Jerome by the "Master of the Osservanza", 1436

If there is a monk in the church ask to be shown the sacristy (through a door to the right of the altar): it contains a further wonderful polychrome terracotta group mourning the dead Christ attributed to Giocamo Cozzarelli. This is more mannerist in style, with the various saints and apostles striking intensely tragic attitudes. Off the sacristy is a small museum with illuminated manuscripts; beautifully embroidered old vestments; some - mostly modest - paintings and statues (good but damaged fresco of St Michael the Archangel, originally from the crypt); and other odds and ends.

The altar and the chancel suffered most from the bombing and are a complete reconstruction.

(1980s and 2015)