|

On his 91st birthday

CONTENTS

Birth in India and early visits to the UK

Education in England: prep school

At public school: Cheltenham 1935-39

The war - Cheltenham and Cambridge 1939-41

Call up and the journey out to India 1941

Officer Training School at Mhow 1941-42

Bengal and the India-Burma border 1943-44

Back to Blighty and Cambridge Part 2 1945-47

High Commission in Delhi 1947-50

Back to Europe and The Hague 1950-53

Back to the UK and Paris 1958-60

Foreign Office: 1961-64 and New York 1964-68

Back in Delhi 1968-69 and Sussex University 1970

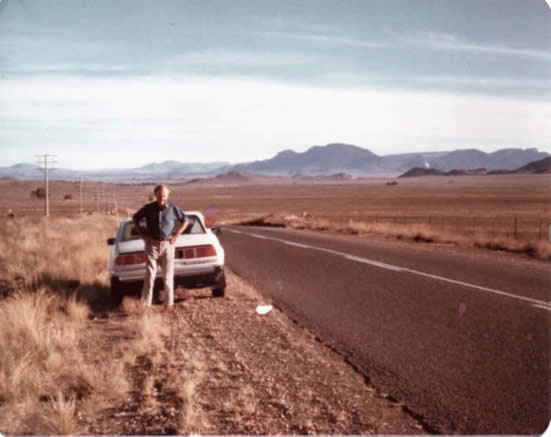

South Africa 1978-80 and trips to India

Appendix 1 GRIGOR and TAYLOR ANCESTRY

Appendix 2 John (Jack) McLeod Grigor Taylor

Birth in India and early visits to UK

John Grigor Taylor was born on 25 November 1921 at a military maternity hospital in Ahmednagar, some 300 miles east of Bombay, where his father, a Major in the Indian Army, was stationed.

John (always known as Jack) McLeod Grigor Taylor was then 37 and his wife, Dora Ducé, was 28. She was a schoolteacher who had met Jack when she had come out to India to visit her sister Madge, who was then married to an engineer working in India. Dora and Jack were married in early 1921 in Poona (now Pune).

John was their only child and the three of them formed a loving family for the rest of Jack and Dora’s lives. After John’s birth, Jack wrote to his own mother:

It all seems so wonderful. I don’t feel that I will fully realise the presence of our John until Dora and he come back to the bungalow from hospital. He really is an absolute gem. I’ve already seen one or two babies of about the same age in the hospital (quite an epidemic!) and they don’t compare. … As for Dora, she is in the seventh heaven of happiness and looks it all over. … Oh! He is capital and I shall be glad when I get him into the house, to just sit and watch him whenever I come in. …

On Thursday 24th, ominous symptoms began to quietly assert themselves and I drove Dora to the hospital at 3 p.m. – not without a little insistence, for she hated leaving home altho’ glad of it after. That night the labour commenced in fits and starts and the little boy came into the world at noon 25th November.

I was away at work at 11 a.m., four miles away, when I received a chit from the Doctor to say that “things had started” and Dora ought to be a mother in a few hours, and hinting that I should keep away until the evening, when the birth was expected.

Some local horse races (the first for 10 years) were on that afternoon. I started off for them at 2 p.m. and, bulging with curiosity en route, decided to “drop in” and secretly ascertain how things were going. Left the trap outside and tip-toed into the room. Imagine my surprise when Dora, from behind a screen, hearing my footsteps, looked round from the bed and said “Look, Jack”, pointing to the little darling at her side. Two hours old, he knew his Daddy at once, came rushing in to my arms (ahem!) and I nursed him to sleep for half an hour. Then on to the Races – the middle of them. Everyone seemed genuinely delighted with the news (this is not my imagination – you see, they all love Dora so much) and I beamed more and more as the afternoon wore on.

The following year, the family returned to the UK on home leave, which normally happened every fourth year for the Services in India, and stayed several months. They seem to have stayed at least part of the time with John’s aunt Madge at Abbey Gate Cottage at the entrance of the ruined Beaulieu Abbey. This was next to Palace House, the seat of Lord Montagu, one of Madge’s many admirers, who had lent her the cottage. Photographs show that Jack Taylor and family visited Madge and Dora’s mother, Lilian Ducé, at 56 Aberdeen Road in Highbury, London. They almost certainly also went to Bakewell, where Jack’s sister Dorothy and his mother (usually known as Granny Grigor but more properly Margaret (Maggie) Taylor) were living.

John with his grandmother Lilian Ducé in Islington

Back in India, Jack was posted to the North West Frontier, in what were the dying years of the Great Game. Jack was engaged on operations, so Dora and John stayed at Dera Ismail Khan, a fortress in the North West Frontier Province at a safe distance from the wilder tribal territory. John’s earliest Indian memory is of the battlements of the fortress.

John with his ayah, probably Dera Ismail Khan, c. 1923

In 1925 or 1926, the family went back for another home leave, again staying with Madge at Beaulieu and visiting Jack’s family in Bakewell and Dora’s in London. John can just remember this UK visit. Two women in particular made an impression on him. The first, “Auntie Pearl”, Lady Armstrong, the wife of the then head of the Royal Automobile Club; had a hoarse voice and four chows with blue tongues. The second was Lady Troubridge, a prolific writer of romantic novels. On meeting John, she said: “so you’ve just come back from India, John; what was it like?” – to which John replied in a very Indian accent: “very cold” (they had presumably come back during the winter when it can be quite cold in North India). “Oh”, Lady Troubridge said, “it has been much belied”. Lady Troubridge was the sister-in-law of Una Troubridge, the lover of the lesbian novelist Radclyffe Hall. John remembered a story about Una Troubridge’s son Vincent pointing out Radclyffe Hall in a restaurant and saying to his companion: “you see that chap over there? She’s my uncle”.

Another memory of this trip was hearing wireless through loudspeakers (as opposed to earphones) for the first time, a matter of amazement for both John and his mother. It was also about this time that a regular air service was established between the UK and India, so that letters took only a few days to arrive rather than three to four weeks. John was, however, disappointed by birdsong. He had read about it in children’s books and imagined that the birds in England sang real songs with voices and tunes. He asked his mother if he could go and listen to the birds singing and was taken into the garden where the birds were chirruping, only to ask “when are they going to start singing?”

Jack’s regiment was the Rajputana Rifles (or Raj Rif). From 1926 to 1929, Jack was posted to Nasirabad, about nine miles from Ajmer in Rajputana (as Rajasthan was then called). John retained vivid and happy memories of the family’s time there.

Nasirabad served as the “cantonment” for Ajmer, i.e. the base for the troops responsible for the maintenance of local order (cantonments were often located some few miles outside the town they were protecting). The other role of those in the Cantonment was to keep an eye on the semi-independent princely states which surrounded it. There were normally also a battalion (700 men) of British infantry and a battery (300) of British gunners in the cantonment. In addition, it was the depot for the Rajputana Rifles – i.e. where the archives and other possessions of the regiment were kept and where new recruits were first brought and trained. The five regular battalions of the Raj Rif, known by their numbers 1 to 5, were stationed all over Asia as part of the imperial system of keeping order and defending frontiers. Each battalion kept an officer to represent its interests at the depot. Jack was from 2 Raj Rif and was also deputy Commandant of the depot. The father of John’s life-long friend John ffrench represented 4 Raj Rif. The recruits came from rural areas of Rajputana and the Punjab and arrived looking lean and hungry for their 6-12 month induction training; with good nourishment they put on weight so rapidly that Jack said it was like watching a speeded up film.

The family lived in a largish white-washed bungalow made of muttee, a mixture of mud and straw, with a thatched roof. A ceiling cloth was suspended under the roof to catch insects and snakes – John remembers seeing signs of them wriggling above the cloth.

At first, there were no telephones, electricity or refrigeration, and all the water was brought in tin cans or animal skins by a bhishti, a water-carrier (like Gunga Din). Fans (punkas) were operated during the hot weather by a man pulling a string from outside the room (when electricity arrived, during the course of their time there, John remembers his mother explaining that the punka-wala would no longer be needed, but John remembers with nostalgia the slow rhythm of the fans pulled by human power as much more agreeable than the steady hum of the electric fans.) When the hot weather began, “hot weather precautions” were taken: “chicks” or bamboo screens were drawn down over all the windows and “khus khus tatties” – screens made of dried foliage - were installed. Water was frequently flung over the tatties and its evaporation created a welcome cool draught.

John with his mother. Note the warlike toy

John had first an ayah (an Indian nanny) and then a male bearer to look after him – he thinks his mother replaced the ayah so as not to have a rival female influence over him. The bearer, Jagarnath, was gentle and respectful, and reproachful where a European nanny would have been angry – “oh no, John Sahib, you must not do that” instead of “how dare you!” His mother still played a hands-on role in his care, bathing him in a tin bath (which he liked), putting him to bed etc. He played a lot in the garden of the bungalow, where he had a small flower-bed in which he used to plant things. He remembered with nostalgia to the end of his life the smell of newly watered hot Indian earth.

Much of the garden, however, was a battlefield for his toy soldiers, of which he had some 60 or 70. He acquired more when he went back to school in England, spending 1/6d (7½ p) out of his 2/6d weekly pocket money on a box of eight each week, building up a collection of some 700. These sort of lead soldiers now command high prices; unfortunately, at some point they were put in the care of a friend who disposed of them, allegedly for patriotic wartime purposes, much to John’s chagrin. To make up the numbers in Nasirabad days, John used to collect chips of wood from the sawmills in Kashmir, his “woodens”, which he would pretend were also soldiers – they would often be made to play the enemy. Jack’s Indian orderly, who had served like Jack in Mesopotamia during the First World War, dug a system of mini-trenches for John’s soldiers, and also made tents from brown paper weighed down with pebbles in which the soldiers slept, and “barbed wire” out of string and twigs.

John playing miniature military games

Whenever John went outside, he had to wear a topi, even in the cold season – the received wisdom was that something disastrous would happen to a European child if its head was exposed for more than few moments to the Indian sun.

John remembers his father arriving back in the evening, a creaking and attractively leather-smelling giant in his high leather boots, uniform with Sam Browne belt, often a sword (if he had been on parade) and sometimes a pistol. John loved the huge male presence of his father, representing a quite different and wider world from the soft and cuddly one of the bungalow. Jack would sometimes sit down, put up his legs, take out his pistol and take pot-shots at tins on the veranda, letting John help pull the trigger. John greatly enjoyed this. Occasionally Jack would bring his horse up to the bungalow as well and try to lead it into the sitting-room to tease Dora (the horse was called Wallaby and was a “Waler” from New South Wales, as Australian horses were thought better able to resist the diseases of India than British-bred ones). Jack also used to encourage John to feed the horse – something John never particularly enjoyed, not being at all horsy, although he adopted the animal talk that he later used towards dogs from his father’s converse with his horse.

John on his father's charger

John remembers his father as always busy, either at work or at play – Jack was an excellent sportsman, keen on and skilled at shooting, riding, polo, hockey and pig-sticking (the dangerous sport of hunting wild boar on horseback and spearing them). Jack often played these sports with his soldiers, from whose company he clearly derived much happiness. Although many of his attitudes were imperialist, even racist by our standards, he dearly loved his Indian soldiers and often encouraged John to come and meet them and listen to their tales (communication was almost entirely in Hindustani).

This photo has a caption by John’s father:

“A great soldier & soldier son, Nasirabad 1928”

The bungalow was one of a dozen in the cantonment occupied by officers and senior civilians, some of them Indians (the doctor, for instance, was an Indian). John and his ayah or bearer would often go for walks along “The Mall”, the main street of bungalows, to the maidan, a plain on the edge of the cantonment which merged into open country. The maidan included an air-strip and a golf course. The latter was just sun-baked earth and burnt grass indistinguishable from the rest of the maidan apart from the greens, which were known as “browns” and made of specially smoothed and watered brown sand.

The church and the British military hospital were within the cantonment; John remembers that the ledges on the back of the pews on which prayer-books are rested had wedges cut out of them as a prop for each soldier’s to rifle in, because ever since the Indian Mutiny, 80 years earlier, when the British were taken by surprise unarmed during a church service, it was routine for soldiers to take their weapons into church with them. The War Memorial for Raj Rif troops killed in the First World War was also in the Cantonment and one of John’s early memories was of the ceremony for its (rather belated) unveiling in January 1927 – marked by a huge parade, commanded by John’s father, to which all battalions sent contingents. To one side of the parade grounds were the lines, the rows of huts occupied by the troops. On New Year’s Day, another great parade took place on the maidan, of which the high-light for John was the Rifles firing in sequence, some thousand men one after another, making a noise that he likened to that of tearing cloth.

The Cantonment also included “the Club”, which had a tiny green lawn kept carefully watered. The children were taken to play at the Club by their ayahs or bearers, who would squat on their haunches watching their charges play games such as tiddly-winks and snakes-and-ladders. The parents would sit around surveying the scene while sipping their lime squashes or gin and tonics. The children were also allowed to go, suitably accompanied, to a shop in Nasirabad town run by a Parsee called Framjee where they could buy “approved” sweets in proper wrappers. John remembers that, in contrast to India after Independence, many of the goods in the shop were British branded ones (Kia-Ora orange squash, Bryant and May matches, Marmite etc) – a concomitant of empire.

Cows in the regimental dairy provided milk and very thin butter. Meat – probably buffalo – was dark and boring. Eggs were miniscule; the chickens, albeit scrawny, were a popular item. But the best food was the game that Jack bagged on shooting expeditions every weekend – goose, duck, snipe, quail, partridge, jungle fowl (the ancestor of our chickens) and sandgrouse. Jack used to come back and lay out the contents of his bag in a row and explain to John what each bird was. He remembers snipe as being particularly delicious. There was a good supply of fruit, and the Indian cooks really excelled at every type of pudding, especially complicated affairs with spun sugar. John also remembers his mother cooking meringues by placing them on the inside of the lid of a big square biscuit tin and putting it out in the sun on the kitchen steps – perhaps with another tin lid attached to the wall at an angle to reflect even more sun onto the meringues. When electricity arrived in the late 20s, refrigerated trains became a possibility, and John remembers the delights of tasting “real English butter”, as well as such delicacies as kippers and bacon.

In about May, John and his mother would go up to Kashmir for two to three months to escape the hot weather. Apart from working women – doctors, nurses, missionaries – and a few intrepid young wives, all the European women and children used to go up the hills for the summer, to one of some eight or ten hill stations used also by the troops along the 2,000 miles of the foothills of the Himalayas, from Dharamsala in the west to Darjeeling in the east. Kashmir was considered the premier station and most expensive, so Jack was pampering his family by sending them there. He would normally take a week’s leave to take them there (which took three days by train and then car). They would go first to Srinagar where they stayed on a houseboat from which John would swim with water-wings in the Dal Lake; and then on to Gulmarg, higher up in the hills, where they would stay at Nedou’s hotel (destroyed in one of the Indo-Pakistan wars).

Shikara on Dal Lake 1920s

For John, Gulmarg was an enormous treat. He would ride on little ponies or “tats”, about the size of a Shetland pony, led by a syce or groom – usually a little boy of six or seven, barely older than him. He would play in the little rills tumbling down from the mountains, making boats and dams. There were also lots of children’s parties with paper hats and games. For most of the families the hill stations gave them a much wider choice of (European) acquaintance than in their normal station, as families came from all over India, so there was an intense social life. John also remembers the wonderful fruit: every week it seemed that there was something new – apricots, nectarines, paw-paws.

John grew up speaking Hindustani to the servants and to his father’s men and English to his parents and the other Europeans, in his early years with an Indian accent. By way of education, John went with three or four other English children to classes with Mrs ffrench, who had been a governess before her marriage. At one point, a Christian Anglo-Indian (ie mixed race) girl appears to have given the children religious knowledge lessons, as his mother recalled that, during the trip to England in 1926, John saw a religious picture and said:

“Oh look, there’s Jesus”

Religion had not been much in evidence in Jack and Dora’s household, and Dora, intrigued, asked him who Jesus was.

“Jesus is a very important man who kills you if you are naughty”.

His mother, also a teacher by training, helped teach him to read and write – he can recall suddenly realising he could read by himself at the age of five while looking at The House on Pooh Corner. He used to read squatting on his haunches Indian style, his cheek pressed against his knee and the book open on the ground in front of him. Since none of the women who taught seemed to be any good at arithmetic, however, it did not figure prominently on his curriculum.

Education in England - prep school

When John was eight, his mother took him back to England to go to school there. John ffrench went with his mother at the same time, and from then on the two boys tended to go or be taken everywhere together, with their respective mothers and their families in England taking it turns to look after them. So John ffrench became the nearest to a brother that John ever had.

John and Dora travelled back on the SS Cracovia of the Lloyd Triestino line. Dora greatly preferred this free and easy Italian company to the prim and stuffy P & O which was the great imperial British shipping company. On P & O, as soon as the ship sailed, the passengers would be dragged out of their cabins to the usually cold and draughty boat deck for lifeboat drill, whereas the Italians did not bother. When, about a week into the three week trip, there had been no boat drill, Dora asked one of the ship’s officers when it would be. He was dismissive, saying to her amusement:

“But if the big boat sinks, what good will the little boats be?”

At one point, John and his mother were invited onto the bridge, where the captain suggested that John press one of the buttons. It turned out to be the foghorn – again it would have been unimaginable for a P & O captain to allow a child to try the foghorn, however good the weather. And one of the high points of the trip back was when the ship passed an Italian destroyer in the Suez Canal and the latter fired a salute (this was in the days of Italian imperial ambitions). During the voyage, Dora decided that John should grow out of his “woodens” and surreptitiously threw them overboard, for which he ever afterwards mockingly reproached her as a lesson in betrayal.

When they got to England, Dora took John on the usual round of visits to the family, and then left John in the care of Mrs ffrench, who had taken a house in Prince’s Risborough. John always regretted that his parents tended not to take their own house, but to share (no doubt partly for financial reasons as money was always tight). He felt strongly the need of somewhere which was seen as his home and where he would be the host and child in charge when other children visited.

Mrs ffrench put the two boys for two terms into a small school in Prince’s Risborough which took boys and girls, but the boys only up to the age of eight. The two Johns were deliberately made to board to prepare them for the rigours of the proper boarding Preparatory School for which they were destined, even though Mrs ffrench’s house was only a few hundred yards away. John remembers enjoying Woodlands, especially the girls who used to mother him (and he decided that when he was grown up he would marry a particularly nice girl some years older than him). On his first day, another boy called John Marshall came up to him and asked John whether he would be his chum. John agreed. John Marshall’s father was a vicar who suffered from back problems and he would pay his son 2d a week to massage his back. The 2d (about 1p) was spent on buying a chocolate wafer biscuit, and the chumship’s sole manifestation, as far as John could remember was the weekly presentation to him of half the chocolate wafer. John was unable to reciprocate, not having the financial wherewithal to do so.

John’s other memory was of singing sessions, gathered round the teacher at the piano to sing popular songs, a session that was normally followed by tea and biscuits John enjoyed these sessions and, having a remarkable musical memory, could still remember the songs into old age. On one occasion, the teacher asked if the children wanted to continue the session “after tea and biscuits”. They all chorused “yes, please” except John, who – more out of a sense of non-conformity than anything else – said sotto voce “no, thank you”. To his embarrassment the teacher heard and asked why he did not want to continue. He quickly said that he did really want to go on, thus establishing a life-long pattern of – in his own words - being a rebel but not a martyr.

In the autumn of 1930 the two Johns moved to Dorset House Prep School, where they stayed for the next five years. All new boys were put automatically in the bottom class to begin with, regardless of age. Within two or three days, John had impressed enough, despite his lack of formal education, to be elevated two forms. It took John ffrench rather longer.

It is not clear why their parents chose this particular school in Littlehampton, Sussex, typical of many at the period – owned and run by the headmaster, Mr Munro (whose father had founded the school) and with some 40-60 boys (the numbers fluctuated, presumably with the state of the economy), many with parents in India. The headmaster and his wife were in their 60s, and he tended to impress parents as an amusing old Scottish savant, while she appeared kind and motherly. Little did they know. Within a term of the boys joining the school, she was killed in a car accident and thereafter Mr Munro’s previously largely latent homosexual urges manifested themselves. He would invite boys into his room for sex lessons and fiddle with them to make a point. That is as far as it got with John, but he had no doubt it went further with boys who responded in any way. All the boys knew of and disliked these activities and used to discuss how to avoid them (there were some unfortunate victims whom he positively pursued). But in those innocent days they had no idea what it was about, and whether it was a normal part of school education, so nothing was ever mentioned to parents.

The situation was probably saved by the deputy headmaster, Mr Sims, who seems to have become aware of what was happening and, about half-way through the stay of the two Johns, persuaded the headmaster (perhaps with a strong element of pressure) to sell him the school. Sims, although less likeable in the eyes of parents, was efficient and recruited two enthusiastic young masters, just down from Oxbridge, which improved the school no end.

Above all, however, John found himself part of a dominant clique of some four or five exceptionally congenial, alert and intelligent boys, mostly with Indian connections, and that is what really made the school a happy place for him, even while Munro was still in charge. They read, talked and invented ingenious games, and for John it was an intellectually and artistically stimulating place that Cheltenham - with the disciplines and pressures of a big school - never was. Together with the leader of this band of boys, David Butler (who was killed in the war), John founded a successful school newspaper called “Ye Moan” which boys had to pay to read, the normal currency being cigarette cards. John heard that “Ye Moan” survived and thrived after his departure.. At the end of his time at Dorset House, John managed to get an exhibition to Cheltenham, worth £60 a year, roughly the fees for one term.

Like many schools of that period, it did have its sadistic aspects. John remembers one occasion when one poor boy, who had been condemned by the sixth form (the justice administering body) for being “uppity”, was made to run the gauntlet of all the boys in the school, who hit him with gym-shoes as he passed between them. John was deeply uneasy about this, and alone of all the boys refused to participate, remaining at his desk throughout, and expressing sympathy to the victim afterwards.

During the holidays, the two boys used to stay with Madge, who had by this time moved to Colgrims, a house on the Solent that she had purchased and enlarged with a modern extension designed by two young (and later highly influential) architects, Amyas Connell and Basil Ward (sadly the house no longer exists).

Colgrims

John’s mother, unusually among parents based in India and probably at considerable expense, used to make a point of coming over at least once a year, but John did not see his father once during the five years he was at Dorset House, although Jack wrote lively weekly letters (which he continued doing to the end of his life). Dora would normally arrive for Christmas and stay often until June or July, leaving Jack behind in India (much of the time on active service on the North-West frontier). When she was there, the boys led an organised and happy life with regular walks, outings and meals. But when they were alone with Madge, they were left to their own devices, and felt a sense of loneliness. John remembers playing endless games of soldiers, with battles lasting four or five days. The boys also made tree houses and gorse houses and went for long cycle rides along the then quiet country roads – they used for instance arrange to meet a boy living 30 miles away at the half-way point between their homes for a picnic.

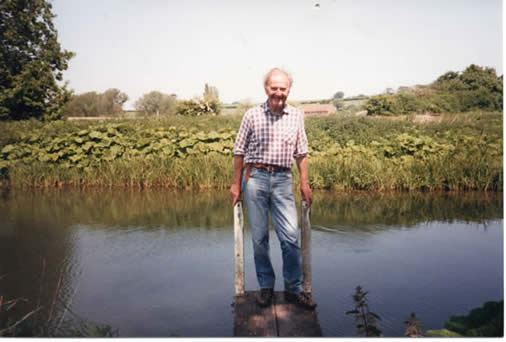

John with his mother c.1935

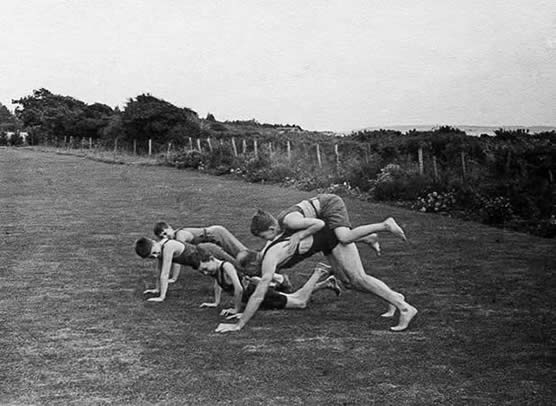

Press-ups with Jack (foreground) after he returned from India

At public school - Cheltenham 1935-40

In 1935, John went to Cheltenham, a public school with a strong military tradition. It had been his father’s school and was also that attended by his three Brooke-Taylor cousins John, Mike and David. For the boys, the House that they were in, and its Housemaster, were all-important. John, like his cousins, was in Christowe, presided over by Wilfred King, a middle-aged bachelor, a survivor from the First World War in which he was badly wounded and awarded the Military Cross. He was the embodiment of clean-living,

dedicated church-going puritanism, with limited awareness of contemporary pressures and issues. The house adapted to his image. He had a private income and – whereas traditionally housemasters counted on making money out of their tenure - King actually spent his income on the boys, who were as a result the best fed in the school, with food bordering on the luxurious for those days.

Otherwise, the living conditions were austere, with bare concrete stairs and no heating in the dormitories (in which the boys slept in cubicles). Every morning the boys were made to strip off in public for hot showers (while the hot water lasted) in the communal wash-house, but otherwise all washing was in cold water. Every hour of the day was regimented (including on Saturdays), with gobbled meals being fitted in briefly between lessons, two prayer sessions a day, organised sports and two hours prep from 7 to 9 pm after supper. There was a lot of beating, both by the housemaster, often at the request of form masters, and by prefects if boys had violated house rules. During John’s time there, however, the tide was turning against beating, and it was beginning to taper off; and John managed to emerge without once being beaten, although when he was head of house he was reluctantly involved in beating one boy for a particularly flagrant abuse.

John was an active member of the debating society and was on its committee. Generally, however, the level of intellectual interest was low. Only two other boys in John’s group were intellectually talented and one became his best friend (he also was killed in the Second World War). John remembers one period during which the Philistine atmosphere in Christowe was notably lightened. This was when there was a polio scare and all boys were isolated in their houses for two weeks, unable to attend lessons (as these were normally held in the main school buildings). The individual houses were left to make their own arrangements and the Christowe housemaster encouraged the boys to form a committee to organise lessons. It was summer and the weather was good, so the boys used to sit in the garden while the senior ones taught the more junior. John was by this time in the sixth form, and he helped to supervise Greek, Latin, English and French. This taste of unregimented learning was much enjoyed by all, and there was a perceptible awakening of interest in things of the mind. Normally, the spirit of the house was very much based on sport and the boys were not used to talking to each other about other subjects (not least because boys sharing a house did not necessarily go to the same lessons). Quite a few boys had exams coming up, however, and even the less intellectual were keen not to fall behind and participated keenly in the lessons. The contact of boys with boys, with the brighter ones helping the less bright and the older the younger (something normally discouraged to avoid unhealthy relationships) seems to have led - even if only temporarily - to an unusual commitment to work with even the some of the heartiest boys showing an interest in poetry and composition.

John enjoyed Corps, being interested in all things military, and rapidly got promotion. However, sports were the be-all and end-all (rugby in winter and cricket in summer), and being good at them was considered far more praiseworthy than intellectual prowess. John disliked organised sports, but fortunately found that at the age of 15 he could opt during the summer for rowing instead of cricket. He enjoyed rowing (which involved a bus ride to Tewkesbury), and was also good at it (he was in the school’s 1st IV), thus saving his reputation as a sportsman. But generally he greatly resented the time given to sports. Cheltenham was surrounded by the beautiful Cotswold country which he longed to be out in, as for him the countryside was what England was all about, and he felt thoroughly frustrated at the hours boys were compelled to spend on sports, for example for the whole of summer Saturday afternoons from 2 to 6 pm, leaving only Sunday for bicycle rides to the country.

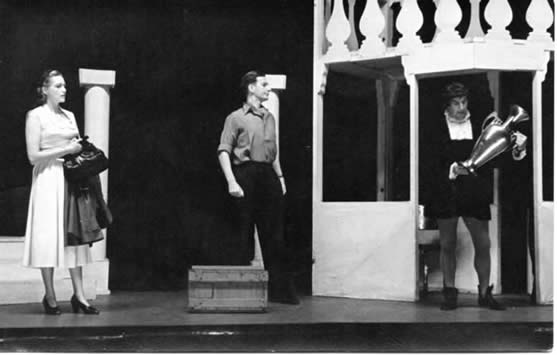

John second from left. Three of the five boys on this boat were killed in the war.

John passed his school certificate (the equivalent of GCSEs) within a year of arriving at Cheltenham and, because it was what bright boys were supposed to do, was put onto classics, which he did for the rest of his time there. Classics – and above all the endless composition of Greek and Latin prose and verse that they then consisted of - was not his forte, and he felt he did less well than if he might have, had he been allowed to do something he liked such as history or modern languages.

As for the holidays, John’s father retired from the Indian Army on reaching the age of 50 (the normal retiring age) at about the time that John went to Cheltenham. His parents returned the UK, staying first with Madge at Colgrims and with other relations and then in a rented house in Pinner, where his father trained for a second career as a golf course manager. So John was able to spend his holidays from Cheltenham with his parents. John ffrench, whose father was younger and still serving in India, often joined them (his parents had sent him to another public school, Blundells).

John with his parents outside Colgrims

John did not dislike Cheltenham, but nor did he particularly enjoy it. He felt that the main things that it had given him were a determination to take some exercise every day and an ability to get on quickly and without fuss with the everyday processes of life.

The war - Cheltenham and Cambridge

In 1938, when Germany annexed Czechoslovak Sudetenland and war seemed imminent, Cheltenham prepared to put itself on a war footing by setting the boys to build trenches, as seen in the photograph below. The Munich Agreement then supervened. The Second World War finally broke out on 3 September 1939, about three weeks before the autumn term at Cheltenham was due to begin. Many of the older boys left early to join the armed forces. The parents of the others received a letter to say that the War Office had requisitioned the buildings at Cheltenham and that the school was being evacuated to Shrewsbury, to share the facilities of the public school there. So the next two terms the boys boxed and coxed with their peers at Shrewsbury, the Shrewsbury boys having lessons in the morning and games in the afternoon and the Cheltenham boys doing their lessons in the morning and their games in the afternoon.

Digging trenches in 1938

As there was not enough dormitory space, the Cheltenham boys were billeted on local families. John, along with two others (including his great friend Tony Townsend-Rose) stayed with an elderly childless couple, the “Sandfords of the Isle” (after land that they owned in an oxbow of the Severn and to distinguish them from another branch of the Sandford family) in a country house about three miles outside Shrewsbury. The boys bicycled in each day, often through the frozen snow as 1939/40 was an exceptionally cold winter.

Despite the cold, the boys much enjoyed their time at Shrewsbury. The Shrewsbury boys were friendly, and the Sandfords lived in some style, with maids and a semi-formal dinner. They were kind to the boys, but lived in a world of their own. This was the time of the “phony war” when very little was happening, and the boys used to talk cynically about the war lasting 20 years and about the Germans being so much more efficient that they would be bound to beat us (this was a deliberate tease of the adults). This distressed the Sandfords, who told the boys that they need not fear as Britain had a secret weapon. The boys looked bemused, and the Sandfords, after glancing at each other and saying “shall we tell them?” took them out on to the terrace and pointed to Venus, which had recently appeared in the evening sky. They explained that it was an artificial star that would defeat German weapons. It was quite clear that they really believed this. At that time the authorities were putting about all sorts of stories about secret weapons and super-human facilities (like pilots being trained to have cat’s eyes), so belief in an artificial star was not totally daft. But the more worldly-wise boys were naturally incredulous, although they politely withheld expressing their incredulity until they were out of the hearing of their hosts.

By the 1940 summer term, the War Office decided that it did not need Cheltenham after all, and the boys returned there. This was John’s final term. In the summer holidays, as part of the war effort, John joined a party of boys from Christowe on a farm on the Cotswolds to work as agricultural labourers in the place of the men who had been called up. Their chief work was to get in the harvest, stacking the sheaves of corn into stooks to dry in the sun and wind, and then loading them onto horse-drawn wagons to be to be taken to where the corn-ricks were built (in the days before combine harvesters, corn was stored in ricks for several months before being threshed). John also looked after the pigs, feeding them and cleaning out their stalls. He grew very fond of them, and to the end of his days could not pass a pig without trying to scratch its back. A bevy of mothers and daughters organised the camp where the boys stayed, cooking meals etc. The presence of the daughters added greatly to the pleasures of that phony war summer, and John took particularly to the sister of his friend Tony Townsend-Rose.

Dora watching boys stacking corn at Tally-Ho farm, 1940

All the boys knew that they would be called up shortly for war service, although during the phony war period the Army was not taking that many people and the normal call-up age was 19 or more. For younger people like John on the brink of going to university, there was an arrangement whereby the Army agreed to defer call-up if possible for at least two university terms if the person concerned signed on and took the oath – ie undertaking that they would come as soon as called up – before they went to university. John had already registered himself at Cheltenham as wanting to join the Indian Army, and now took the oath before going up to Cambridge, where he managed to stay for six months, the equivalent of a full academic year, before being called up.

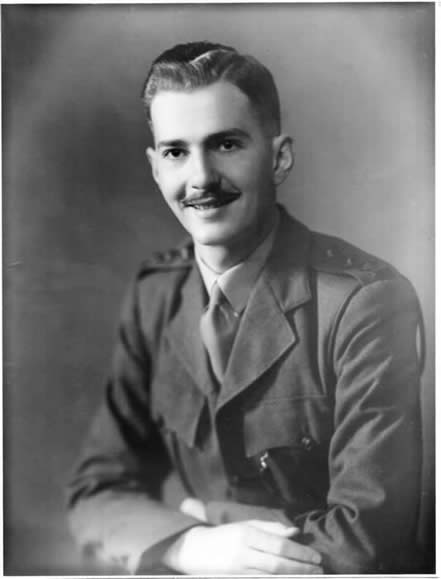

John at Cambridge c.1940

John went up to Christ’s College Cambridge in the autumn of 1940 to read economics, which he chose as a complete contrast to classics. He went to Christ’s on the advice of his form master, an old Christ’s man; and his mother, who had ascertained that Christ’s was a college where many of the students were poor and John would not be despised for his lack of money. Even at Christ’s, he found he had less than most other undergraduates, as his parents could afford no more than £10 a term spending money. His father had joined the RAF as a squadron leader in an administrative capacity at the approach to war, so with his pension and additional RAF pay, he had around £1,000 a year, not bad for the period. But he was not a good manager of money and a lot seems to have gone on betting on horses. Indeed, it is unclear how his parents could have afforded to keep John at Cambridge the full three years if the war had not supervened.

£10 a term was sufficient to pay for no more than two or three beers a week, and John became proficient at economising. He made a resolution which lasted until late in his life never to buy newspapers (which could be read in the library) or coffee after meals. He quite often cut dinner in Hall (which cost 1/6d), and sometimes literally went hungry. His friends told him later that they were really quite worried about him. Nevertheless, he greatly enjoyed Cambridge and does not remember feeling left out because of lack of cash. He loved being among old and beautiful buildings; the freedom of an undergraduate after the discipline at school; and the many lectures outside his subject that he could attend by figures such as Bertrand Russell (on philosophy) and Cecil Day Lewis (on poetry). The Spanish Civil War – an event that had polarised politics in Britain - had recently ended and John was left-wing in his views. He joined the Cambridge University Socialist Society, a communist front organisation. The possibility of an invasion was very real at that stage and John and his friends would discuss taking to the hills as guerrillas if the Germans came. He was also a member of the Home Guard and would patrol outside Cambridge to spot low-flying aircraft, although none ever came close enough to him to shoot. His parents were by then living close by (his father was the RAF movements officer for East Anglia), and his mother used to come over regularly for tea.

Cambridge still had college servants or “gyps”, mostly old soldiers, veterans of the First World War, as all the able-bodied younger men had been called up. The gyp on John’s staircase used to wake him in the morning with remarks such as “they’ve dropped another of them insanitary [i.e. incendiary] bombs last night”. He told John that if one peed in the trenches it stirred up the mustard gas and “gets you in the privates”. The gyps were supposed to do all sorts of odd-jobs for the undergraduates, but did the minimum necessary unless well tipped, which John could not afford to do.

John was going out with his first serious girlfriend at this time, Claire Townsend-Rose. He told his parents that he had been genuinely in love with her and it was a long time before he felt the same about anybody else. But the relationship did not survive the long wartime separation, although John continued to have fond memories of her. Her brother Tony, John’s old Cheltenham friend, became an engineer who joined the Railway Inspectorate, and remained a life-long friend of John. His son Richard was one of John’s many god-children.

John had been accepted for an Officer Cadet Training Unit in India on the strength of his OTC training at Cheltenham and at Cambridge, where he had also served in the Home Guard. However, it was always uncertain when convoys to India would leave, so when he was first called up in the summer of 1941, he and his fellow would-be Indian Army officers were enlisted in the Royal Scots and mustered for training at a depot at Aldershot. They were private soldiers, but wore a piece of white cloth under their shoulder badges to show that they had been accepted for officer training. There were some 200 of them, including a few Indian boys who happened to be living in Britain at the outbreak of war. About 90% were from Public Schools. John made some of his lifelong friends in those six weeks.

John after enlistment with his aunt Madge in Red Cross uniform.

The young men were allowed out at weekends and it was during one of those weekends that John almost got a lift from Queen Victoria’s youngest son, the Duke of Connaught, as he often recalled later. He and two others were offered a lift by a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce. The other two took the lift but John was going in another direction. In the back of the car was a very old man, and the chauffeur said “make sure you give him a smart salute when you leave, as he is a Field Marshal”. This was the Duke of Connaught. He was born in 1850, and his godfather was the Duke of Wellington who died in 1852, so for John he represented an impressive link with the past.

Before their final leave prior to embarkation, the old Scottish Sergeant-Major in charge of them (whom they all thought a dear man) a homily about the need to be back on time:

“Gentlemen, as we are in times of war, the full penalties of military law apply. If you are even a minute late, you will be guilty of Desertion in the Face of the Enemy, the penalty for which is death by shooting. As we have only one weapon available, my personal revolver, I shall be obliged to carry out this uncongenial duty myself. Spare me the pains, gentlemen, spare me the pains. Enjoy your leave. Dismiss”.

A bit of a ceremony was always made of embarkation, and they all marched from Aldershot to the station in their smartest kit lead by a band and pipers, while by-standers – including John’s mother – lined the route to watch. Their destination was supposed to be a deadly secret, but they had all been issued with sun helmets that had to be carried attached to their packs, giving a pretty fair clue. They boarded the train at 3 pm, and remained on it for some 24 hours, with no idea at all of where it was going. There was a lot of shunting and shuffling, punctuated by the thumps and bangs of occasional air-raids as they went round the edge of towns. At one point in the middle of the night, they recognised Newcastle. Finally they arrived, rather to their surprise, in Gourock, near Glasgow, and were marched to lighters, moored on the Clyde which ferried them to the SS Strathallan, a luxury P & O liner that had been commandeered and converted into a troopship.

Cadets marching off to war in India

Extract from letter from John to his parents

OCTU, Aldershot, 5 July 1941

Time at last for another scrawl. It’s Saturday afternoon and the rest of the day is mostly free. I am lying in a top bunk in the barrack room in my shirtsleeves eating NAAFI chocolate and feeling very pleased with life. I may say now (in order to prepare you for future shocks) that one’s attitude to army life, in the ranks in particular, varies considerably. It seems inevitable that there are times when you are fairly “browned off” and fed up with the whole show, and the chief bugbear of the Private’s life can be summed up comprehensibly in the expressive word “bullshit”. This is alluded to by the officers (at least in the presence of [other] ranks) as “discipline” and includes every sort of red tape and what appears to the ranks as aggravating attention to unnecessary detail, which is shortly contradicted. On the whole, however, one can laughingly grouse at these annoyances and soon forget them.

Last night, I spent about two hours chatting alone with a Sergeant and a Private (seven years’ service) in the Scots Guards and they both summed up all the grievances of their past service by saying they would jump at the opportunity of having it over again – in spite of the “bullshit”, which is rife in the Guards, of course. …

Anyhow, to get back to the world of fact, everything is fine and I feel very fit. Half the unit has gone on leave, so everything is free from the usual congestion. There are only four men in the barrack room out of about 28. We have been issued with everything now and are well on the way to complete soldierdom. The kit is of very good quality, considering everything issued – toothbrush, razor, black towels, underpants, tropical kit, topees – in fact everything that the ordinary soldier possesses, minus one suit of B.O. [body armour] My boots are taking some breaking in. I’ve burnt, honed, spit and polished them for about 3-4 hours and a dull shine is beginning to appear. My guardsman friend said he had a bad pair which didn’t develop a full shine for three years! As you know, we wear Balmoral bonnets with white OCTU band and white shoulder-flashes. A friend who has gone on leave up to Glasgie and is “verra Scots” is getting me a walking our Glengarrie if he can.

Nearly all our work so far has been drill under Guards Sergeants. P.T. under a very good Army P.T. instructor who makes the whole thing like a game, and one or two very good general lectures on India, Security etc. …

The SS Strathallan carried several thousand soldiers, most of whom were cockney Gunners going out to Singapore to serve with the British Army there (less than half probably survived the war). The total living-space was less than that of a tennis court for the 200 cadets in John’s group who were on the lowest deck, beneath the waterline. The deck was open-plan. Tables, each taking about a dozen men, took up most of the floor space, and there were showers and latrines at one end. The men could either sleep on the tables (or the floor), or on hammocks slung above the tables (John’s choice). The only light was from dim electric bulbs. John thinks that there may have been a deliberate decision to put the future officer cadets in the worst accommodation, to give them a sharp taste of how ordinary soldiers lived.

The first week aboard was spent sitting in the Clyde waiting for the convoy to be mustered. There were often air raids (this was the period of heavy German bombardment). One of the episodes of John’s army career most reminiscent of the “carry on” films was the “short arm” inspection that took place on deck while they were waiting in the Clyde. A doctor came on board to inspect them for venereal disease, and an officer lined up all the men in two rows on deck, facing the sea. The officer himself stood in front of them with his back to the sea and barked out an order to them to drop their pants. There was some murmuring among the men and one or two voices began tentatively “Sir...” The officer, furious, shouted “silence” and the men did as they were told. Behind him a launch was passing with a naval officer and four Wrens, who waved appreciatively at the sight, whereupon the men dissolved into laughter and their officer at last turned round, apologising “sorry, men, pants up.”

The voyage to India took six weeks. The convoy was a fine sight: about a dozen liners, some huge, managed by up to four or five destroyers, working like sheep-dogs around the big ships. The time was mostly taken up with a mixture of PT, weapons training and Hindustani lessons. The men also took it in turns to do lookout duty either for enemy submarines or for aircraft. John and a friend were allocated to an anti-aircraft turret, a small steel box with a gun, built on stilts some 15 feet above the deck and reached by an iron ladder. It was at the stern, which took a lot of the ship’s movement, and both John and his friend were as sick as dogs. They once spotted a German reconnaissance aircraft several miles off, obviously shadowing them. This was often the prelude to attack, but that convoy was lucky and was not attacked, whereas the convoys before and after both had ships sunk (and the Strathallan herself was torpedoed off North Africa a couple of years later). The convoy started out by heading North and one night in the Denmark Straights, between Iceland and Greenland, John and his friend saw the Aurora Borealis. At first they debated whether it was an enemy manifestation - perhaps aircraft using searchlights - that they should report, but then luckily realised what it was and did not make fools of themselves.

Life below deck was quite a shock to the system for these eighteen or nineteen-year-olds from relatively protected backgrounds, but John remembers it as a tough but jolly time. The men were allowed out only on one deck, reached by climbing numerous flights of steps. However, they would sometimes sneak out at night and use the swimming pool; John remembers their bodies in the pool glowing with phosphorus, and also watching the phosphorescent flying fish alongside the ship. Their duties included orderly duty – scrubbing and cleaning and also washing up. Every soldier was issued with his personal tin plate, knife, fork and spoon. They pooled these and collected them together in a bucket of water at the end of each meal to be washed up by the two men doing orderly duty for that table. The water in the buckets was pretty murky, and on two separate occasions at John’s table the cutlery was thrown out to sea by mistake with the dirty water. As there were no replacements, for the final two weeks of the journey the men at that table were obliged to eat with shoe-horns, scissors, combs, nail-files or anything else that they could find. Porridge was a particular challenge.

The convoy twice touched at port en route. The first stop was in Freetown in Sierra Leone where the men, to their frustration, were not allowed to disembark. John remembers the inhabitants coming up the ship in canoes shouting jolly obscenities such as “I fucked Queen Victoria” and selling bananas. The next stop was Cape Town for three or four days, where the men were at last allowed off the ship. They were given a little lecture about not going to District 6 (a famously tough area) where they might be knifed; and remembering to use French letters (probably unnecessary; for that was an innocent age and the vast majority had no sexual experience and were far too terrified to experiment with strange girls in Cape Town). Then, tremendously excited, they flooded ashore. In the event, the women who accosted them turned out to be highly respectable middle-aged or elderly ladies in cars from Cape Town’s white community, who charitably took them back to their houses for meals and much needed baths. The family that John was with wrote afterwards to his mother and they stayed in touch for many years.

Extracts from John’s letters about the journey out

On board H.M.T. -----------, 1 August 1941.

John has scribbled out some words in this letter that he thought would not pass the censor.

… It is illegal to keep a diary on board ship owing to the rather odd censorship regulations. Thus, if possible, I intend to write to you at odd times during the voyage and post it all, subject to censorship, at X, our first stop.

Much water has sizzled by the sides since I wrote the previous page. Life has been very full and at times quite exciting – the really monotonous part probably lies ahead. My first note from on board, if it got through anywhere near intact, must have appeared rather depressing. It really was one of the most shattering disappointments I have incurred to see our living quarters after viewing the fine exterior of the ship. At first one felt a sort of mild claustrophobia, which at times made you feel frantic with desperation at being cooped up below the water-line, a hundred men in a room (perhaps twice the size of the Gonville dining-room), with a scull-cracking roof, all equipment hopelessly jumbled and partially lost – incredible inefficiency all round. Above decks, the officers’ quarters with magnificent decks, bars, clean table linen daily, 4-course breakfast, 6-course dinner.

It was a good experience as it really made you feel what it must be like to be an East End slum child looking at West End revelry. Conditions, however, gradually improved. Familiarity bred contempt [five words scribbled out]. We were moved to a deck above the water-line with much more space. Soon, the really excellent canteen opened – as much chocolate as wanted, crates of lovely oranges, apples and biscuits, all products of the Union of South Africa. In fact, nearly everything we live on has been imported, and it is rather comforting to think we are taking nothing out of the country.

Our situation in port was simply glorious – no more can be said for security’s sake, but we were all very impatient to sail. One rather amusing incident happened in port. A large party of us were paraded on deck preparatory to undertaking a medical once-over. We were stripped to the waist and the sergeant shouted, “Come on, down with your pants. The ladies on shore (which was some way off) haven’t got telescopes”. We promptly obeyed and stood in solemn silence, paraded in the buff, as our batty adjutant (who practises yoga) calls it. Next, chugging gently past the ship, glides a large private launch with three women lying on the deck! Hoots, cheers and catcalls from masses of troops dancing up and down in the nude. Everyone was howling with laughter, including the crew of the launch. It was a frightfully amusing situation, especially as the man piloting the launch, looking very much like papa, very non-plussed, sped off at full speed.

12 August 1941 [same letter]

… It really amazes me how adaptable we mortals are over such a short space of time. It was as though I had been brought up to life on a trooper. Squash – four square inches for personal belongings – horrible unwashed bustle in the mornings (reveille at 6.0) – food not at all bad – fatigues (mess orderly) , scrubbing, polishing, scraping for half the morning in an atmosphere in which the sweat stands out on you and trickles down even when you are sitting still. Then the officers down from the West End [3 words deleted or censored], it seems. They all shout different things at you and talk about the honour of having the Captain’s cake [sic] for the cleanest mess deck, while you are yearning for your first glimpse of daylight on deck and your first visit to the latrines. However, once over it, all fades quickly and you are making the most of a really pleasant piece of existence, lying cushioned on the deck on your “Mae West” life-jacket with the lovely clean breeze sweeping you. Probably sucking a superb orange or apple – and gazing out at all the interesting censorable things going on in the convoy, or the uncensorable things like the incredibly blue sea producing in some manner, which will always be miraculous to me, a dazzling white bubbling line of foam.

Yes, there have been some very memorable and unique moments, even living in such human, almost sub-human, conditions. When we first sailed in the twilight, the coast of Britain slipping away in a kaleidoscope of every type of beautiful scenery, rugged mountains, fresh sweet tidy fields, white sandy beaches. Then the lone watches of 12 p.m. to 2 p.m. – bitterly cold sometimes with the fog swirling around, the louring forms of the ships and – night of nights – the Aurora and the glow of the midnight sun. “Look”, said John Stagg, my gun-mate, “A search-light beam in the sky!” But it flickered and went – and then the whole sky was rippling with beams and bars and flashes of dazzling light which shaded sometimes to a green or blue tint. “By Jove, John”, again pointing to the horizon, “a heavenly host of angels!” And then up above for a minute a broad, magnificent V hung – what an omen!

Once we clambered clumsily up to our turret, shrinking from the gale, but now we can stick our hammocks on deck and it is simply glorious. We lean over the rails and watch the phosphorous wake, before climbing into our cosy hammocks. Also we now have a tropical sunset at 7.30 – the sea all red and gold and silver and the edges of the western clouds flaming neon ribbons. Then at 8 o’clock, much to our surprise, we go on deck to find it so dark that you have to feel your way.

These are the better moments, but life seems much smoother now. Sleeping on deck is a great boon. We seem to get quite a lot of spare time to lie on the deck during the day between parades, but little time for serious reading. One either washes, sleeps, learns a little Urdu [these last words were partially scribbled out] or just lies. Space is fairly scarce even on deck and cries of those engaged on “housey-housey” [bingo] re-echo through the deck. Kit is fairly satisfactory. They have raped our suitcases from us into a hold, but we can get at them. There is nothing to buy except food – the only drink available is a poor [word scribbled out] beer, 4d. a bottle and the most expensive drink on the boat. Gin and It 3½d. a glass, for officers only, and ditto with every other kind of drink. ... However, under the exigencies of a troop deck full of moribund cadets, permission was given for us to obtain a pick-me-up through the platoon sergeants. John Stagg and myself took advantage of this and had a blissful strong brandy and ginger ale before flopping into our hammocks. After that we felt all right. …

Mhow, 20 October 1941

… Cape Town – a magnificent interlude – in a rather trying ordeal. I sent you some silk stockings from there by the way, Mummy, in one of the few moments I had to draw breath. We got four days in. I was mess orderly the day we put in and there was a heavy sea running – almost as bad as the early days in the North Atlantic. However, it was a poor day and the far-famed approach to Table Bay was largely lost in mist. In an interval of [being] mess orderly, I got up on deck to empty a refuse pail and saw the vast bank of mountain suddenly tower out of the mist, looking very dull, grey and blank. The next I saw was when I went up after we had docked, just before lunch. The deck was covered with troops and the sun had broken through. I climbed onto a hatch and peered over the heads to see this great square rugged mountain with a sharp conical offspring on one side – Lion’s Head – and a bright smokeless town clinging round the water’s edge.

Of course we’d all had lectures on where to go and where not to, and on the general geography of the peninsula and were all eagerly picking out spots. In the last few days we had bullshit (!) as far as conditions had allowed and managed to make ourselves fairly spick and span. Now, would we get ashore today? Everyone was speculating. A large gunner edged up and confided that he was the C.O.’s orderly and we would get leave from 14.00 to 29.59 hours.

He was right. We got our two pounds pay in Cape currency and pushed down the gangway onto LAND – after five weeks. We all capered. It was a lovely spring-like day. I was with John Stagg and Peter Wickham. A vast column of khaki and blue streamed towards the dock gates. As we got out, sort of W.V.S. women issued us with maps and guides. We took ourselves straight to the main Adderley Street and just gaped at the lovely American cars, the shops full of food, fruit and every kind of food, the negroes and the white women! We had gaped for about 10 seconds when a rather withered elderly lady came up to us and asked in a slightly Dutch accent if we would like to have tea with her. We said yes, thank you very much, and we were led to the most magnificent restaurant in the town, the Del Monico, with a band, a roof made like an artificial canopy of stars – and carpets and chairs with backs. We were just overwhelmed. We had a super tea and then the old girl (her name was Mrs Knox, widow of an Irishman, last war) made us promise to meet her the next day immediately we got ashore, about two, and go for a drive. Peter had to go back to the ship on guard duty, so John and I strolled up Adderley Street to gape at the lights, which were just beginning.

Again we were drifting off and just deciding to have a colossal binge somewhere, when a car glided up (the universal large shiny American type) and a middle-aged woman asked if we would like to come to supper. We hopped in and were introduced to two very pleasant women – Miss Godleston [?], woman secretary of the R.A.C. in South Africa – she had met Sir Frank Armstrong [head of the R.A.C.] – and Miss Vos, schoolteacher, Dutch extraction. Both were frightfully nice, and although both were about 30 had a very good idea about how to entertain boys of our age. We drove first up to the Vos house in one of the upper suburbs – Oranjezicht – just at the base of the mountain above the town.

Then we drove out of the town along a mountain road which carried us all round the bay to a spot called Constantine [mistake for Constantia] Nek about 20 miles away. It was simply superb – incredibly lovely, with the lovely bright beams of the car sweeping the mountain woods and veldt, and yawning away beneath us a magnificent gallery of lights, , neon signs on small sky-scrapers, ships outlined, necklaces of street lights climbing hills! At the Nek (a saddle between mountains) was a roadhouse where we had an enormous mixed grill and ices.

We still hadn’t got over our black-out complex, so you can imagine how breath-taking was the effect of the light streaming out over the valley and on the mountain side. Well, I could just pile on this stuff about the natural and artificial beauties of the Cape, but to sum it up, in normal times, the scenery and grandeur, the cleanliness and efficiency, the food and the kindness would have impressed us; after five weeks of boat and a couple of years of rations and black-out…….! Besides, I am using up my statutory eight sides of paper and this is a very expensive letter, so I must summarise. After Constantia Nek, we went to the oldest house in the colony, Steinberg, which belonged to Miss Godleston’s married sister – 1682, with stoops and things, and we drank Dutch liqueurs.

Well, we “did” every possible thing on the Cape peninsula. Were driven dozens of miles. Had the largest and most enjoyable lunch of my life in the crack restaurant with Peter, John and Colin [Mayhew]. Met all sorts of interesting people. Went up Table Mountain and saw the most glorious and overwhelming view that I shall probably ever see in my life at sunset.

And so after the most crowded four days – again probably of my life – back to the long dragging days of mess orderly, sitting on deck chewing biscuits, singing, gazing out to sea, sleeping, a lot of P.T and Urdu. Every day, however, brought us nearer destination “V”. At last we put into Bombay on a Sunday morning, disembarked straight onto a native troop train for – to our surprise and consternation – Mhow. The train was from 6 p.m. to 3 p.m. the next day – congested hell which we now accepted as the day’s work and enjoyed the journey enormously, for whatever else, we were on India and land.

We pulled into Mhow, full of apprehension, not knowing the first thing about the place, and were half afraid we would be bundled into barracks once more. Well, now we’re here with a month’s training behind us and fully settled in. There was a first fine careless rapture when we saw our mess room and ante-room; when we could taste cool iced drinks again; be waited upon by uniformed bearers the whole time; eat with knives and forks; sleep between sheets; have hot baths – and generally speaking be treated as gentlemen.

Then the real life of the school. The O.T.S. [Officer Training School] Mhow has the reputation of being of the hardest and most efficient O.T.S. in India. The drill standard and general bullshit in which the school excels exceeds that of the Guards and Sandhurst, as ex-officers of both institutions testify. We arise at 5.30. An hour’s drill and an hour’s P.T. before breakfast. Then continuously on the go until about 4, with half an hour for lunch and 20 minutes for breakfast. Compulsory exercise in the evening and often night ops. Bed never before 10 with one hour’s prep in no night ops nights. I am in “B” Company, as you see. We have about 115 men, several from India. The other half of our draft, going for RIASC [Royal Indian Army Service Corps] and cavalry are formed into “F” company. Six Companies in the school. Part of Colonel ffrench’s draft form “C” Company. The other Companies are all Indians or Anglo-Indians. Some very good fellows. Must stop now. Life’s on the whole settled and pleasant. …

Officer Training School at Mhow 1941-42

The men were given lectures on board ship about life in India (which was to John a pretty distant memory), but nothing really prepared them for the shouting, heaving masses of Bombay when they arrived there in September 1941. John’s other memory of Bombay was the way that everything was lit up at night (the Japanese had not yet entered the war so India was not under attack) in contrast to the blackout that had been darkening Britain at night to confuse the German bombers.

The men were given no time in Bombay; they disembarked with their huge packs straight on to trains alongside the ship. There followed a hard 15-hour journey – no concession was made to the fact that they were officers-in-waiting, and they travelled in the same trains as were used for transporting the Indian troops, with rough army meals, hard wooden seats and little protection from the cold as they ascended into the hills. Late at night they arrived at Mhow, a small central Indian town (near Indore in Madhya Pradesh) where there had been an Indian Army garrison before the war, now transformed into an Officer Training School. They were accommodated either in ancient barracks or temporary huts. After the ship and the train, they were amazed at the luxury, two men to a room with sheets and mosquito nets. The toilets were thunderboxes – commodes with buckets underneath – and a sweeper (an “untouchable” servant who did all the menial tasks) was summoned to empty the buckets after use. This was to be their home for the next six months.

John (on the left) 36 hours after arriving in India

Photo taken by John of his fellow cadets

John enjoyed Mhow chiefly because of the easy camaraderie among the men. Everyone was jolly and companionable. They may have been frustrated by the lack of sex, but obscene jokes and cheap booze made up for a lot, and John made several of his life-long friends there (he was known as “Grigor” and those who knew him then call him that for the rest of their lives). The training consisted of the predictable lectures and lessons on map-reading, strategy, weapons etc. The instructing officers were both European and Indian. In their spare time, the men used to go off on bicycles to the surrounding country with a picnic; John remembers in particular a waterfall about five or six miles away where they would swim.

Serrgeant Taylor (second left) with fellow cadets at Mhow

At Christmas, he was invited along with three others to the home of one of the cadets, Lexie Walford, whose father was a judge in Lucknow, a sophisticated, largely Moslem city in North India. They had only a week’s leave and four of the seven days were spent on the train journey there and back, but for John it was well worth it. The Judge was the best sort of servant of the Raj, literate and liberal, with many Indian friends with whom the Walford family mixed socially on an equal basis. As a result, during his short stay John met a good cross-section of the educated Indian elite of Lucknow, from politicians to poets; and he also visited some of the old buildings of the city and began to acquire a taste for Indian art and architecture.

Extracts from John’s letters from Mhow

Continuation of letter of 20 October 1941 (see above)

At last we put into Bombay on a Sunday morning, disembarked straight onto a native troop train for – to our surprise and consternation – Mhow. The train was from 6 p.m. to 3 p.m. the next day – congested hell which we now accepted as the day’s work and enjoyed the journey enormously, for whatever else, we were on India and land.

We pulled into Mhow, full of apprehension, not knowing the first thing about the place, and were half afraid we would be bundled into barracks once more. Well, now we’re here with a month’s training behind us and fully settled in. There was a first fine careless rapture when we saw our mess room and ante-room; when we could taste cool iced drinks again; be waited upon by uniformed bearers the whole time; eat with knives and forks; sleep between sheets; have hot baths – and generally speaking be treated as gentlemen.

Then the real life of the school. The O.T.S. [Officer Training School] Mhow has the reputation of being of the hardest and most efficient O.T.S. in India. The drill standard and general bullshit in which the school excels exceeds that of the Guards and Sandhurst, as ex-officers of both institutions testify. We arise at 5.30. An hour’s drill and an hour’s P.T. before breakfast. Then continuously on the go until about 4, with half an hour for lunch and 20 minutes for breakfast. Compulsory exercise in the evening and often night ops. Bed never before 10 with one hour’s prep in no night ops nights. I am in “B” Company, as you see. We have about 115 men, several from India. The other half of our draft, going for RIASC [Royal Indian Army Service Corps] and cavalry are formed into “F” company. Six Companies in the school. Part of Colonel ffrench’s draft form “C” Company. The other Companies are all Indians or Anglo-Indians. Some very good fellows. Must stop now. Life’s on the whole settled and pleasant. …

Mhow, 9 November 1941

… Well, what haven’t I told you about? An awful lot, but it is hard to know where to begin as usual. A catalogue of facts will have to serve the purpose. I am very fit – weigh 11 stone 9 lbs, which is five more than on enlistment. Alternate and normal waves of constipation and diarrhoea, rather like a trade cycle (at the present moment I am midway between boom and bust and therefore “thik and achcha” [OK and good]). They are common to most and also very mild. I had one serious bout soon after I arrived which hovered on the verge of dysentery, but was only indisposed for a week. I shared this attack with about half the company – I think it was India’s welcome. Peter Wickham retired to hospital with dysentery proper for three weeks. Poor old Colin [Mayhew] has had two goes of malaria already – first time in India, too, but he’s fit now. Otherwise I have been on tip-top form – my next worst ailment being an ant-bite on the left elbow which I received while out on night trench-digging, i.e. dozing on my back on the maidan [open space near the barracks] – a habit which many of our night operations here cultivate.

Perhaps I ought to harp back and give you my first impressions of India. I have just written a footling essay on the subject in which I adequately buttered up the Indian Army and got B+; others wrote good literature but the truth and got C-.

It was hot, although I believe the rains had passed over Bombay. Not as hot as we had had it, though. Very calm. As the new, rather depleted convoy approached India, little fishing boats appeared. I was, as always seemed to happen when approaching port, below deck swabbing up some filth or other, and my first impressions of Mother India were through a crack though a supposedly blacked-out porthole in the reeking galley. Bombay was lovely to look at, and that’s as much as we experienced of it.

We docked and spent hours standing or sitting on deck, while the old Strathallan disgorged thousands of troops on to the quay. We were the last unit to get off and during our last hour on board invaded the officers’ mess and sat in chairs for the first time in ages and drank iced drinks. Then our turn came towards evening. We shuffled about the quay in odd queues and great howling and yelling masses of coolies descended upon us, much to our delight, and relieved us of our sea-kit. We were both intrigued and entranced by the happy-go-lucky, noisy, Indian (as per novels Hindoo Holiday and E.M. Forster) way everything happened.

Eventually we moved off a few hundred yards to a siding where we found a very dirty train. More noise and quite a lot of considerateness on the part of the authorities – cigarettes (which I swapped – I still hold out), tea and buns issued, also blankets. A party of us drifted along the quay to where our old escorting cruiser was moored. It seems so long ago now. Much to our delight, we were invited on board and were shown many of the secrets of the ship in a half-hour before a shrill whistle recalled us to our train. It was the first warship I have been aboard and I was very impressed. Also similar reaction, as with everyone, to the spirit and work of the Navy all through. A nice bit of depth-charging and many other manoeuvres carried out in the course of the voyage.

Back to train. Tearful farewells and wild cheering as we steamed out of the station, leaving all our old officers, some of whom were real cards. Then we passed slowly through the squalid suburbs of Bombay in the dusk. Great amusement at the mass of Indians, all of whom looked very cheery and grinned and waved to us in return. Cries of “Tuck your shirt in” and “Go and put your clothes on” from some Signals who were with us. Great amusement at the notice “Lavatories – Indian style”. Then night. Dirty, excited and dog-tired, we wrapped ourselves up in a blanket, squashed onto wooden shelves provided and went straight to sleep. Dawn. 5 a.m. Change at Khandwa. We struggled out onto the platform with our baggage, the quintessence of scruffiness, unwashed in our salt water scrubbed K.D. [khaki drill uniform] – and had breakfast – bread, tea, meat and bananas.

Then, into another train. We passed through fairly open country – bit of scrub – a few buffaloes and palm trees, and all surprisingly green and not very un-English. Of course it was just after the rains. Then over a vast river on a trembling viaduct and into hill country. Up and up to about 1500 [feet]. Up a glorious valley like Dovedale – our first monkeys – and lunch at a place called Kalakund. Then on to an open plateau towards large white-washed barracks – MHOW. Nearly two months from door to door and to the hour.

This must be all for the present. This letter will cost another fortune, although it doesn’t matter now as I have received my first pay.

… I share a room with J.H. Stagg, Esq. Our room is above the mess. The curriculum of the school is, as I have already mentioned, I believe, rather unsatisfactory. … By a stroke of false judgement on the part of my platoon, I was elected Commander of the Company. On the strength of this, I have been honoured in the first batch of promotions (which are effected with toadying and lucky number) and made a Lt/Cpl for a month (temp. rank). I’ll send you a photo of my stripe later.

Mhow, 23 November 1941

…The days seem to fly by so incredibly quickly. I might have been at Mhow a life-time, yet it seems I have hardly had time to draw breath between Sunday and Sunday. It is now Sunday evening and most people are out at the pictures. With our mess kit we carry canes and wear a forage cap of khaki serge, which matches very ill with the rest of the kit, so the general effect is a cross between an A/C 2 [Aircrafttsman 2nd Class] and a West Point cadet. I am rather tired, so it is difficult to write anything coherent. This seems the right context for giving you a schedule of our working day here, which I don’t think I have done hitherto.

5.30: Reveille (this means get up as opposed to Wilbers [probably the barracks where John stayed in Aldershot] and the Strathallan, where you could ignore reveille for half an hour). Wash, shave, dress etc.

6.30: Parade (usually drill. Wear numbers on our chests for all parades and the slightest movement will probably result in number taken and extra parade on our two free evenings).

7.45: Double up to gym and engage in the most strenuous P.T. I’ve ever met, for about an hour. Also boxing, unarmed combat, running thrown in.

9.45: Back to change for breakfast, which is gobbled down in 15-20 minutes.

9.20: On Parade again until