7. THE LAMBERT GORWYNS OF SPREYTON AND HAVEN HOUSE

- George Lambert Gorwyn I (1763-1837)

- George Lambert Gorwyn II (1796-1850

- George Lambert Gorwyn III (1796-1850)

- Richard Lambert Gorwyn (1819-1861)

- Grace Lambert Gorwyn, née Howard

- The descendants of Richard Lambert Gorwyn (1820-1861) of Haven House

- The Canns of Fuidge

George Lambert Gorwyn I (1763-1837)

The youngest son of John Lambert Gorwyn of Lambert, George Lambert Gorwyn I (1763-1837) was perhaps the most successful of the four surviving sons of John and his wife Mary Cann. He was the first of a dynasty of six Georges (see Table 4), to whom I am giving numbers like monarchs to distinguish them from each other. He was also one of the few members of the family to move away from the Cheriton Bishop area, although only to the nearby village of Spreyton (his great-great-grandson Michael Lambert was fond of saying that the family moved only five miles in a thousand years).

The church of St Michael and All Saints at Spreyton

George I started off lucky by being the main heir of his maternal bachelor uncle, George Cann, who may well also have been his godfather (a position taken seriously in those days). He inherited a number of farms in Spreyton and Hittisleigh from his uncle, including Falkedon, a largish farm in the parish of Spreyton with a very nice old cob and thatch farmhouse with six or seven bedrooms (which was still in use by his descendants until the 1960s). Falkedon seems always to have commanded the affection of its occupants; George Cann’s brother William, who was probably brought up there, gave instructions in his will for his body to be conveyed by bier from his home in Hittisleigh to Falkedon and to rest there overnight before being buried in Spreyton Church under the Falkedon pew in a coffin of good English oak. After the death of George Cann in a riding accident in 1804, George Lambert Gorwyn I took over the house at Falkedon. He remained for the rest of his relatively long life, obviously a brooding presence, as well into the 20th century his great-grandchildren still knew him from their parents’ tales as ‘the old boy of Falkedon’.

The farmhouse at Falkedon, in the 1950s (the thatch was subsequently replaced with slate).

The other property that George inherited from his uncle George Cann included the farms of Coffins, Croft and Rugroad in Spreyton and a third share in some lucrative lime quarries and kilns in Drewsteignton. He may also have inherited quite a lot of money from George Cann, as in the years after George Cann’s death he appears to have gone on what can only be described as a spending spree. In 1810 he paid £13,000 to buy Crediton Parks, a grand and ancient property in Crediton (the old game-park and hunting ground of the Bishops of Exeter), from the grand and ancient Tuckfield family. And in 1814, he splurged on large chunks of the 1300-acre Medland Manor estate in Cheriton Bishop, which was being sold by the heirs of another grand and ancient Devon family, the Davys. In particular, he acquired Medland Manor itself (described in the sale brochure as a ‘Modern, Substantial, Well-Built Mansion with offices of every description and fit for the reception of a large family, with lawns, shrubberies,’ etc, etc with a farm of 213 acres) for £6,000; and Gorwyn with 117 acres for £2,200, thus becoming the last member of the family to own the original ancestral home. Altogether, at the sale he spent £15,000 plus an additional sum for the timber that was valued subsequently, and acquired some 800 acres of farmland1. So he probably at one time owned some 2,000 acres or more, making him possibly the biggest landowner ever of the family.

But he appears to have over-reached himself with the Medland estate purchases, as there are documents showing that he had to mortgage Crediton Parks and had some difficulty paying the interest, which at one point alone came to some £7,000. He sold Medland Manor and the other Medland estate properties only about 10 years after acquiring them (there are documents in the Devon Record Office indicating that he accepted an offer for £14,000 for the Medland estate from a Mr Francis Harris, but this sale appears to have fallen through and it was sold instead to Mr Seth Hyde).

From then on George I appears to have led a more cautious life. It seems, however, that he had a litigious streak. There are records in the National Archives of two court cases in the 1820s, both involving bitter conflicts with his relations over tiny bits of land that George claimed were his, on somewhat dubious grounds. The legal expenses alone must almost have outweighed the value, and George was hardly short of land.

The first case2 dates back to 1825 and concerned the ownership of a 10-acre plot in Cheriton Bishop called Newtons that George’s mother Mary had purchased from the Fulfords. This case pitted George against his brothers and sisters. Newtons had descended to George’s brother Richard, who had died young leaving a minor son to whom it then passed. That son (called John Richard) himself died in 1809 when he was only 18. John Richard appears to have been befriended by George I, as when he made his will shortly before his early death he was living at Falkedon, and – apart from a few minor bequests – left his estate to George. As a minor, however, he had no power to bequeath freehold property, which all went to his “heir at law” – namely his eldest uncle (and George’s eldest brother) John Lambert Gorwyn of Lambert. George I was apparently already farming Newtons as part of his land when John Richard died, and he appears just to have gone on doing so. John pointed out that the property was a freehold one and wanted to evict him, but apparently was persuaded by his solicitor not to take any legal action against George as it would lead to “an irreconciliable breach between different members of the family”. But John did mention Newtons in his will, bequeathing it to his nephew John Lambert Arden along with other properties. After John’s death in 1823, John Lambert Arden Gorwyn (as he became – see above) promptly took legal action to evict George. The latter then sought to argue that the property was not in fact a freehold one at all, but only leasehold and therefore had rightly come to him as part of John Richard’s personal estate. It is extremely unlikely that the property was a leasehold one, as at the time Mary bought the property from the Fulfords, they were selling everything freehold. George also claimed that the reference to Newtons in John’s will had been forged. The papers in the National Archives do not show what the outcome of the case was, but George seems to have ended up with Newtons, as it was mentioned in his own will.

Two years later, George himself brought legal proceedings against John Lambert Arden Gorwyn to try to get possession of an even smaller plot of land in Crockernwell (a hamlet outside Cheriton Bishop) called Tucker’s Tenement 3. This also had come to John Lambert Gorwyn of Lambert as a freehold property after John Richard’s death, and John had in turn bequeathed it to John Lambert Arden Gorwyn. George sought to argue that, as the property was purchased by John Richard’s trustees out of the latter’s personal estate, it did not really count as a freehold and should have gone to George with the rest of John Richard’s personal estate. As George only took up this case almost 20 years after the death of John Richard, and the property totalled only some 3 acres, it is hard to resist the assumption that he did so out of spite because of the case that John Lambert Arden had brought against him over the ownership of Newtons. Again it is hard to believe that George had a good case, but he nevertheless seems to have ended up with the property, as it was mentioned in his will. No doubt there was a settlement out of court; as John Lambert Gorwyn had built a number of cottages on the plot, George would in any case have had to pay some form of compensation for added value.

George was widowed early on, but seems to have developed a close enough relationship with his housekeeper, Elizabeth Langdon, to leave her £210 and the Golden Lion Inn in Crockernwell together with some adjoining land when he died. Elizabeth Langdon’s son William Langdon is said to be the author - or at any rate the transcriber – of the song “Widecombe Fair”.

When George died, he owned Crediton Parks, ten farms, an inn, various smallholdings and a one-third share of the lucrative Drewsteignton lime quarries. But he was heavily in debt, with an £11,742 mortgage on Crediton Parks and debts of some £9,000 due to others from whom he had borrowed money. These debts were only just covered by the sale of Crediton Parks for £20,000. George’s farm stock and equipment and household effects were also sold at auction, and made a total of £2,610, quite a big sum. There is a document in the National Archives that lists everything sold (with its price and purchaser) that makes fascinating reading4. Judging by the number of people who bought things, it must have been a famous sale, attracting purchasers from far and wide. The farm stock sold included over 200 head of sheep; 73 head of cattle; 26 horses; 18 pigs (not including piglets still suckling); and 2 donkeys. 50 hogshead of cider were also sold for around £2 apiece, as well as farm machinery and large quantities of furniture, crockery, cutlery and linen. The document also suggests that at the time of his death George was himself farming not just Falkedon but also about seven of his other farms, totalling 800-900 acres – a colossal undertaking for the time (although this total includes Coffins, which may have been informally farmed by his son who lived there).

George Lambert Gorwyn II (1796-1850)

George I had only one child, a son also called George. George Lambert Gorwyn II seems to have been a pretty unsatisfactory character. In 1817 he married his second cousin Mary Cann. According to family stories, the marriage was not wanted by either of them; she was only 18 at the time and said to be in love with a soldier. However, Mary was probably considered a considerable heiress as her father had just founded a bank in Exeter (see section on the Canns below) and no doubt both sets of parents saw the marriage as a highly suitable alliance between two important local families. It turned out to be predictably stormy. At one point Mary even ran away to Jersey (not an enterprise lightly undertaken by a married woman in those days), and had to be fetched back by her son George III. George I appears to have done his best for the young couple by purchasing and putting them into Medland Manor in 1814, and the fact that it was sold only 10 years later may have been connected to problems in the marriage.

In 1828, a woman from Cheriton Bishop called Esther Palmer had an illegitimate son called George whom she appears to have cast on the parish5. One of the duties of the Overseers of the Poor was to find out from unmarried mothers who had fathered their child and to make him pay the costs of the lying-in and the child’s maintenance thereafter. The Cheriton Bishop Overseers obtained an affiliation order against George II in respect of Esther Palmer’s son, and George was required to pay the birth expenses and a weekly sum of 2s.for the son’s upkeep so long as he remained a charge on the parish. George appears to have contested the order strongly, as indicated by a letter that he wrote a year later to the magistrates in Crockernwell:

‘Gentlemen,

I wish the Overseers to be apprised that not another shilling shall be appropriated on my behalf towards the support of Esther Palmer’s bastard with which they, with the aid of other revengeful and undue influence, have taken so much unnecessary pains and expense to saddle me till they can muster honesty sufficient among the great ones, to allow the trifling amount of my claim for erecting the stone steps, and fitting up the vestry and school room for them, at the especial request of the whole parish, to be settled - which I am informed a certain overseer was directed a few years ago to do, but was countermanded by his landlord, to cheat me.

The law of affiliation is too oppressive in itself, independent of Magisterial interference in support and defence of the most corrupt perjury ever produced before a Bench. I have however not yet done, and shall no doubt ere long find care, to bring the matter before a higher tribunal, than has hitherto had to decide on its merits.’6

Regardless of whether he was indeed the father of Esther’s child, this letter is that of a man well used to feuding with his neighbours. The Overseers of the Poor, who dealt with affiliation orders, were neighbouring landholders and his peers, and as the occupier of Medland he could expect himself to do a stint as an Overseer himself. The gentry did occasionally impregnate village maidens, but would normally reach a discreet financial arrangement with the girl concerned. So for matters to have reached a pitch where the Overseers imposed an affiliation order must have meant either that George was obnoxious enough to deny his responsibility for the child despite its being clear that he was the father, or that he had made himself so unpopular with his peers that they were prepared to take Esther’s word against his.

From Medland the couple appear to have moved to Coffins in Spreyton, and there too George II seems to have shown a thoroughly quarrelsome streak, as there is a family story about angry tenants turning the couple out of Coffins and dumping their belongings at Spreyton Cross. Their china was allegedly stolen by the local smith, and George II’s great grandson Michael Lambert (1912-1999) remembers the smith of his day, Edwin Hill who descended from that earlier smith, having a remarkably fine set of china.

At the time of the 1841 census, George II’s wife Mary was living alone at Underhill Cottage in Cheriton Bishop with her two sons George and Richard, described as ‘independent’, so she must by then have separated from her husband. Although only these two sons survived, the couple had five children in all between 1791 and 1825. The other two died in infancy, except for one daughter who lived to the age of 15. These many deaths presumably added to the strains on the marriage7.

George I was clearly dubious about leaving his substantial property to his unsatisfactory son, and also appears to have had some sympathy for Mary. When he died, he bequeathed separate annuities to George and Mary, with strict instructions that George should not be able to get his hands on Mary’s annuity. He left his many farms, however, to his two grandsons, George and Richard. Both were minors at the time, and his will appointed trustees to look after their estates, and also to sell his property of Crediton Parks to pay for the boys’ upkeep and education8. His will was made only shortly before he died, and a typically angry and incoherent letter survives from George II to his father’s old lawyer, written before he knew the contents of the will, which shows the state of distrust between father and son:

As I have been prevented from calling on you since my late father’s death, we shall all feel much indebted, if you can make it convenient to attend his funeral as his original legal adviser in our behalf at Falkedon on Tuesday on urgent business.

Your late servant having taken upon himself with his accustomed artifice, to endeavour to deprive us of the benefit of my inheritance by making himself sole executor of (what he calls) his will made so lately as Sunday last of all other days and which he has as yet refused to allow any one on our parts a sight of and believe me, dear Sir, yours faithfully,

George Lambert Gorwyn

PS I learn that my father was much deranged during his few days’ illness tho’ I should be most unwilling to have his late property wasted in unnecessary litigation if we can be honestly dealt with without it.9

George II seems in the end to have decided not to contest the will, but he quarrelled freely with the two trustees appointed in the will to deal with his sons’ affairs during their minority. When the trustees came to auction the farm stock, crops and equipment after his father’s death in 1837, George II refused to allow the purchasers to take away two ricks of wheat and hay at Coffins that had been sold at the auction for £84 and £20. The trustees also reported that George had taken but not paid for £50 of stock and furniture that had been knocked down to him at the auction. In addition, again according to the trustees, he took from the estate, apparently without their permission, an old black horse; a blind pony (so it seems that at least he had a fondness for animals); the oats and timber on the farm at Coffins; a quantity of poultry; china and glass that he claimed belonged to him (perhaps the china that was later stolen by the smith); five gold rings; a necklace; a silver watch; a picture; several books; all his father’s clothes; a snuff-box; the potatoes growing at Croft farm; and crops and manure from Coffins. The trustees assessed the total value of these items at £16010.

During the minority of the two children, the trustees sold leases of all the farms that George I had previously been farming (mostly very short leases, no doubt so as to give the heirs maximum freedom of action when they reached their majority). George II had presumably been occupying Coffins until then for free under an informal arrangement with his father; he now had to pay an annual rent of £68, which cannot have done much for his temper.

George Lambert Gorwyn III

Perhaps not surprisingly, given his upbringing in a thoroughly dysfunctional family11, George Lambert Gorwyn III (1818-1885), the elder of the two surviving boys, was by all accounts a most unpleasant man, quarrelling with his neighbours, harassing his tenants and suing all and sundry. A lawyer’s bill from the 1860s has come down to his descendants, showing him pursuing actions against about three people simultaneously, despite – reading between the lines – strenuous attempts by his lawyer to dissuade him. When he was not quarrelling with his neighbours, he was gambling with them. According to family legend fields were used as stakes, thus explaining some odd boundary quirks between Spreyton farms12. Another example of his perversity is the way that he described himself in the occupation column of the 1871 census as having a ‘life interest in some poor clayland’, with ‘landowner’ added almost as an afterthought. He also added that he was nearly blind from birth, of which no evidence has come down to his descendants, so he must have been indulging in a bout of self-pity. He was also a womaniser, siring at least one illegitimate child. However, he (or at any rate the family generally) seem to have been in good enough odour for the farmer who was renting Coffins in the 1850s to have called one of his children Lucy Laura Lambert and another Susan Jane Gorwyn. He also seems to have been a good steward of his land, and consolidated his position in Spreyton by establishing his (somewhat defective) claim to be Lord of the Manor there.

He appears to have been rather peripatetic in his early years. He certainly seems to have lived part of the time at Coffins, and he may have lived briefly in Cullompton, as he owned a property there and a lease of 1863 describes him as ‘of Cullompton’. But by the 1870s he had moved to another of his properties, Tray Hill in Drewsteignton13. He stayed there until about 1880, when he was ‘burnt out’ (as it was put by an old villager to his grandson Michael Lambert in the 1950s) by a man named Davies who had a grudge against him. Davies and a friend set fire to a woodrick and burnt the whole place down, apart from one barn (a state in which the property remains to this day). George’s daughter Mary was by then on the way, and the family moved temporarily to the small neighbouring farmhouse of Croft (where Mary was born), which George also owned and which happened to be empty, before returning definitively to Coffins. The house at Coffins was at that stage a traditional cob and thatch farmhouse (it was enlarged in 1905 to create a gentleman’s residence), and remained the chief abode of the family until the death of the last (and sixth) George in 1970.

Coffins or Coffyns in about 1900. The bunting may be for Mary Lam bert's wedding.

Coffins or Coffyns in about 1900. The bunting may be for Mary Lam bert's wedding.

In 1874 George III put a notice in the press to the effect that he was dropping the Gorwyn from his name and wished henceforth to be known as George Lambert. The reasons are not entirely clear. The explanation that has come down in the family is that he considered that there were too many illegitimate Gorwyns around (he may have been referring to the family of Henry Lambert Gorwyn, the station-master at Moretonhampstead who was the illegitimate son of a daughter of the Bradleigh family, on which see Chapter 9). Since then his descendants have used only the name Lambert.

Richard Lambert Gorwyn (1819-1861)

In contrast to his brother George III, Richard Lambert Gorwyn was (according to stories in George Lambert’s family) charming and easy-going. The characters of the two men can perhaps be deduced from the items that they took for their personal use from their grandfather’s estate after his death, when they were still teenagers. George took only a horse, saddle and bridle; a snuff-box; and an “apple-engine and cider-press”. Richard took a “piece of gold supposed to be a two guinea piece”; a quantity of tablespoons and teaspoons; 2 pairs of sugar tongs; 1 pepper box; 3 milk jugs; a cream jug; a tea-pot and stand; 2 salt-stands; a punch ladle; a pair of silver buckles; a seal and two pairs of buckles. As most of these items were probably of silver, it seems that he was more refined (and acquisitive) in his tastes than his rougher elder brother14.

Unlike his brother, who managed to hold on to his considerable inheritance, Richard and wife Sarah were extravagant and became heavily indebted. They tried to live above their means, for instance running a pack of hounds (he was Master of the ‘Haven Harriers’)15. Perhaps this is an indication of the awkward social position occupied by all branches of the Lambert Gorwyns in the 19th century. They clearly aimed at being ‘gentry’. But although they mostly owned largish farms and some – especially the William Lamberts of Wallon and the George Lamberts – also had a number of tenants and so a separate income from rents, they were still hands-on managers of their land. In the various annual trade and Post Office directories that were published in the 19th century (the nearest equivalent to our telephone directories), the main inhabitants of each parish were normally listed either as ‘gentry’ or as ‘trade’ (which included the farmers). The Lambert Gorwyns appear to hover between the two, being recorded sometimes as gentry and sometimes as farmers (or yeomen) in the trade section.

Richard’s mistake was probably to try to be a fully blown ‘gentleman’, letting all his property and living in Exeter. While his income was enough for a comfortable life as a rich farmer, it was not necessarily enough for a gentleman of leisure detached from his land..Richard borrowed extensively from his brother. By 1854 was so in debt that, to safeguard his children’s inheritance, he had to sign a deed of settlement with his brother, under which all the income from his properties was made over to George III, to pay the interest on Richard’s debts, with the remainder being handed over by George to Richard for his family’s living expenses. There seems to have been enough money, however, for Richard to continue to live in reasonable style with his family (he had six children – see below and Table 5) in his large house near Exeter until his death in 1861.

Whereas the relationships between the two brothers seem to have been reasonable, with George seemingly prepared to lend Richard money, George was extremely hostile to Richard’s wife, whom he blamed for the family’s extravagance. After Richard died, he pursued Sarah for the repayment of Richard’s debts. According to family legend, at a meeting between them Sarah said that she did not see why George was pressing so hard for repayment as George’s own property was entailed and would come to her children on his death, since he was unmarried. The 48-year old George was so incensed at this prospect that he promptly married his housekeeper, Grace Howard (a farm labourer’s daughter from South Tawton), who was already conveniently pregnant with the next George Lambert.

Grace Lambert Gorwyn, née Howard

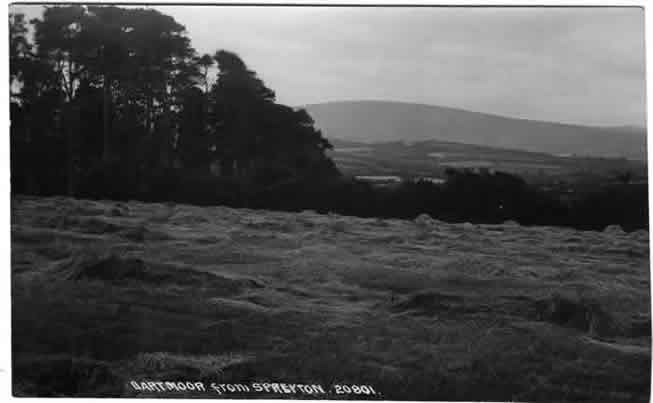

Grace seems to have been the saviour of the family, a woman of character and intelligence who brought up her two children (there was also a daughter, Mary, born in 1880 who married into a well-known Tiverton family) to be well-balanced and socially aware members of society. She was a strong Liberal and encouraged her son to go into local and then national politics. Her obituary notice in a local paper described her as ‘a calm and unfaltering Liberal, whose faith could no more be shaken that could be the granite face of Cawsand Beacon16, upon which, from Spreyton, she had gazed for so many years’.

Old photo of Cawsand Beacon as seen from Spreyton.

No doubt under Grace's influence, the family stopped moving around and stayed firmly at Coffins, which remained the family’s home until the death of her great-grandson, the last George Lambert, in 1970. She was a widow for 20 years after George III died in 1885. His son was then only 19 and his daughter five years old. Grace lived on with her son in Coffins until her death in 1915, keeping a pair of pistols to put across her bedroom doorstep whenever she was left alone in the house. The career of her son George is described in the next chapter.

Grace Lambert in her widowhood

The descendants of Richard Lambert Gorwyn (Table 5)

Richard Lambert Gorwyn (see above) and his wife Sarah led a somewhat nomadic life. By the late 1840s they were living at Higher Budbrooke in Crockernwell (a hamlet between Cheriton Bishp and Drewsteignton), which he seems to have purchased from his cousin John Arden Gorwyn. But it seems that he was already running into financial difficulties, as there is an 1848 sale notice for Higher Budbrooke and its contents in the Devon Record Office. Among the contents of Higher Budbrooke when it was put on the market was a phaeton, an elegant carriage normally affordable by the well-heeled – an indication of Richard and Sarah’s love of the high life. Richard presumably sold Higher Budbrooke as he was prevented by the entail in his grandfather’s will from selling the properties that he had inherited under the will, and that was the only way that he could raise money quickly.

By 1850 Richard and Sarah were living at Belle Parade, Crediton. From there he moved briefly to Paddington in London, where one of his children was born. Then he came back to Devon and moved into Haven House on Haven Banks in Exeter, where the family finally found a permanent home. Despite their continuing financial problems, they lived well, still managing to run the “Haven Harriers”. The house itself was quite a grand one on the banks of the Exe just outside the then city boundaries. When the house was sold after Richard’s and Sarah’s deaths, it was described as a “pleasantly situated freehold residence called Haven House in St Thomas the Apostle, about half a mile from the city of Exeter in the valley of the Exe, consisting of dining, drawing and breakfast rooms, 8 bedrooms, wine cellar, kitchen scullery, coach-house, stable and harness rooms, sheds, walled garden well-stocked with choice fruit trees, greenhouse, summerhouse, croquet ground with a lawn in front, the whole containing about 3 acres 15 perches.....Haven House, to a gentleman requiring a complete residence, offers an opportunity as rarely occurs”17. The building no longer exists and “Haven House” is now a modern office/block of flats.

Richard died in 1861 and Sarah in 1867. His property was left equally between his six children (the entail had ended with his death), but they seem to have delayed selling it. Haven House was let and his three sons appear to have tried to make a go at farming, as they were at Greystone in Drewsteignton (one of the entailed properties) at the time of the 1871 census, the eldest son being described as the head of household and a farmer of 120 acres. But shortly afterwards, the children decided to sell up and Richard’s entire estate, including Haven House, was put up for sale.

His six children were scattered to the four winds. The eldest daughter, Sarah, married a Cornishman, Robert Clegg and moved first to Liskeard and then to Ireland (she had eight children who have many descendants alive today). The other two daughters, Mary and Lucy, also married, Mary apparently to a curate in Bishop Stortford called Edwin Sandys-Reed and Lucy to someone in Brighton. Mysteriously, however, although Mary and her husband are recorded in Bishop’s Stortford in the 1871 census, 10 years later Edwin Sandys-Reed had become the rector of a parish in Kent and was married to a quite different wife. There is a family story that one of Richard’s daughters returned to Exeter and committed suicide on her father’s grave18. If this is true, it could have been Mary. The sister of George Lambert MP (and therefore a first cousin of Richard’s children) is said also to have met one of the daughters who had been to prison; again this is mysterious, but if true it could be Lucy.

The eldest son George and his family (he had at least six children) seem to have emigrated to the United States in about 1879. Richard, the second son, died sometime before the 1901 census, leaving a widow living in Topsham ‘on her own means’ with her six children. The children all had names beginning with H – Hilda, Hylton, Heloise, Horace, Harold, Hector and Hamilton. All survived (apart from Heloise who died in infancy) and produced children, and many of today’s Lambert-Gorwyns are descended from them. The youngest son, Stafford, moved to Somerset, where he was living on an annuity in 1901 (the fact that both Stafford and Richard’s widow could rely on private means indicates that the sale of the properties produced enough to keep the family afloat). Stafford appears only to have had one daughter.

The Canns of Fuidge

It is worth saying something about the Cann family, as two generations of Lambert-Gorwyns of the Lambert and Spreyton branch married into them, and much of that branch’s wealth derived from the Canns.

The Canns are a large and ancient Devon family, spread throughout the county. Somebody has even prepared an extremely fanciful family tree that traces the ancestry of the Spreyton Canns back to a Jean Canne of Chartres, a military companion of William the Conqueror. In fact, it seems that they were no more than yeoman farmers made good. There were Canns in Spreyton at least as early as the 16th century, and by the 17th and 18th century they appear to have become substantial landowners. Some of their wealth came from their ownership of the Drewsteignton lime quarries, which they acquired in 1772 and developed into a highly productive business. They were based at Fuidge, a typical Devon long-house deep in the country south of Spreyton village. In the 18th century, when they became rich, the Canns added an elegant double-bowed front to the house, and built a fine serpentine wall in the garden, making it the most imposing residence in the parish. There were even fish-ponds. Their total estate amounted at that time to some 1500 acres19. There are several monuments to the Canns in Spreyton church.

John Cann of Fuidge (1773-1819), the father of the second Mary Cann to marry into the Lambert Gorwyns, seems to have been a particularly enterprising figure. He raised a company of volunteers during the Napoleonic Wars and was made their captain (many years ago, I found a creamware jug in the Portobello Road Market in London inscribed ‘success to the Vounteers of Spreyton’)20.

John Cann’s next exploit, in about 1816, was to open a bank in Exeter, called the ‘Devonshire Bank’, with two partners, Williams (a former Mayor of Exeter) and Searle. The following year a branch was opened in Okehampton. In 1817 and 1818 the bank issued bank-notes, of which a number survive21. When Captain Cann died in 1819, he left everything to his widow Rebecca, who took his place in the partnership. Unfortunately, there could scarcely have been a worse time for starting a bank, as the boom brought about by the Napoleonic wars was coming to an abrupt end. On 20 December 1820, the bank was forced to suspend payment ‘in consequence of a severe and unexpected run’, and the partners were declared officially bankrupt. Although the partners were jointly and severally liable for all the debts of the bank and Rebecca must have struggled, she managed to retain Fuidge, at any rate for a while, probably because she was responsible only for the debts incurred in the short period when she was a partner. But she no doubt had to mortgage it heavily, and it was finally sold in 1838. Local people could not understand how the Cann fortune could have disappeared so rapidly. Rumour had it that Captain Cann had buried his money under the serpentine wall in the kitchen garden22.

Plaque in Spreyton church commemorating John Cann and his wife Rebecca

Notes

1 Sale documents in the Devon Record Office

2 Lambert v. Gorwyn, National Archives ref: C13/855/6.

3 Gorwyn v. Gorwyn, National Archives ref: C3/873/14.

4 Gorwyn v. Gorwyn, National Archives ref: C13/1176/20. This was a case ostensibly brought by George I’s two minor grandsons and heirs against the executors and trustees of his will, accusing them of maladministration, but in reality it appears to have been mounted by one of the boys’ maternal uncles. The trustees produced full and it seems satisfactory accounts.

5 At the time of the 1821 census, Esther was an apprentice (no doubt as a child learning to be a domestic servant) at Lambert, the house of George’s uncle John Lambert Gorwyn. John died in 1823, and she might then have moved to Medland.

6 Letter of 28.9.1829 in the Devon Record Office.

7 A letter survives from Rebecca Cann, the mother of Mary, which probably refers to one of these deaths: ‘My dear Mary, Your loss is great indeed!!! But I have no doubt hers is gain, which will, I trust, prove when your sudden and heavy affliction is a little assuaged, a heavenly consolation to you. Thank God, she was with you, dear little angel! What a blessed exit!! I hope you will be supported, thro’ this very severe trial, with Christian resignation to the Almighty’s will. I have sent the Picture, but I fear it is not like her. In my will, I have given it to the dear Lamb in remembrance of you. God bless you, my dear Child, and with every kind and affectionate wish from your sisters, I remain your affectionate mother, Rebecca Cann. Monday noon, Dec’er 19th’.

8 According papers in the National Archives (Gorwyn v. Brock, C13/3048/15) from a court case in 1842, Richard, the younger of the two grandsons, thought that the trustees appointed under the will had hung onto some of the proceeds of Crediton Parks that should have been paid to him when he reached his majority. The older grandson George refused to join Richard in his action against the trustees. It is not clear what the result of the case was.

9 Letter of 15.4. 1837, written from Falkedon to Francis Cross, solicitor.

10 National Archives C13/1176/20

11 In 1838, when the boys were still teenagers, they appear to have chosen to live apart from both their parents; George stayed with one of his trustees in Crediton, and Richard with a Mr Pridham, presumably a relation of his grandmother, the wife of George I (C13/1176/20)

12 Although this may just be rumour. The solicitors acting for the vendor of a farm called Fursdon in Hittisleigh wrote to George III’s son, George Lambert MP, in 1918 to ask about the claim of the younger George to a small plot of no particular value on the edge of the farm which local gossip claimed his ancestor had won at cards from a previous owner of Fursdon. George Lambert’s reply made clear that as far as he was concerned the plot, which he had known for 40 years, was part of the neighbouring farm of Westwood that he owned, and that he doubted the story about the game of cards as both Fursdon and Westwood had been owned by his great-grandfather who had divided them between his two grandsons.

13 Now in Hittisleigh following a boundary change.

14 National Archives C13/1176/20.

15 Stories in the family of both George Lambert MP and the descendants of Richard.

16 The great round hill of Dartmoor that is visible from Spreyton.

17 Bill of sale in DRO: 1926B/FU4/3

18 Story in the family of George Lambert MP.

19 Information from Michael Lambert and a 1954 booklet on Spreyton church.

20 Returns in the Public Record Office checked by Michael Lambert show that the Spreyton Volunteers were officially formed on 11.7.1798 and disbanded on 24.4.1802 (after the Peace of Amiens was signed). There is also a footnote about the Volunteers in the Spreyton Parish Register. Captain Cann’s bellicose leanings must then have waned, as there is no sign of the Volunteers being reassembled when war broke out again a few months later and there was a much more real fear of a Napoleonic invasion.

21 Devonshire Bank Notes, Transactions of the Devonshire Association, Vol. LXXX, 1948.

22 Source: Michael Lambert (1912-1999) who did quite a lot of research into the Canns of Fuidge.